Fever and Arthritis

Authors: Marjatta Leirisalo-Repo, M.D., Heikki Repo, M.D.

DEFINITIONS

Arthritis denotes an inflammatory reaction in the joint space. The inflammatory reaction is designated by activation of the innate immune defense mechanisms by e.g., microbial invasion, autoimmune reaction, or synovial deposition of crystals, such as monosodium urate monohydrate or calcium pyrophosphate crystals. The full set of clinical symptoms and signs of acute arthritis comprises swelling representing joint effusion, limited joint motion, tenderness, increased warmth and redness of the skin. Arthralgia is distinct from arthritis and denotes pain of the joint without the other clinical signs of inflammation. Infectious arthritis denotes joint inflammation triggered by a microbe capable of multiplying within the joint tissue. Bacterial arthritis, called also purulent, suppurative, pyogenic or septic arthritis, is a rheumatologic emergency. Reactive arthritis denotes sterile joint inflammation, which is preceded by an infection elsewhere in the body and is typified by the presence of bacterial structures (lipopolysaccharides, called also endotoxin, DNA), but no multiplying bacteria, within the joint space. Immune response to infection, such as hepatitis B virus infection, elicits circulating, complement-binding immune complexes, which may enter the joint and trigger immune complex arthritis. The inflammatory reaction may be confined to the joint compartment, or it may be part of a systemic (generalized) inflammatory reaction going on in the body. Systemic inflammation derives from the activation of the innate immune mechanisms in the circulation and thereby throughout the body. Systemic inflammation may be secondary to a spill-over of pro-inflammatory cytokines from an inflamed joint into the circulation, or it may represent a primary reaction triggered for instance by bacteria, which have entered the circulation and secondarily invade the joint tissue eliciting septic arthritis. Fever is a common clinical sign of systemic inflammation.

Fever denotes an elevation of body temperature above the normal daily variation. The internal normal temperature, measured orally, is about 36.8oC. In addition to fever, increased respiratory rate, increased heart rate and abnormalities in peripheral blood white blood cell (WBC) count and differential cell counts all denote the presence of systemic inflammation. Although joint inflammation is frequently associated with fever, inflammation confined to the joints does not necessarily elicit fever, or elevation of body temperature may be prevented by the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), immunosuppressive drugs, such as glucocorticoids and TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-blocking agents, or by age. Indeed, elderly patients with systemic inflammation associated with sepsis not so infrequently present with normal body temperature. Finally, febrile patients with severe sepsis may present with vital organ dysfunction so that the physician does not necessarily pay attention to “less urgent” problems such as the presence of infectious arthritis. In this chapter, we focus on adult patients with acute arthritis and fever. As to autoinflammatory syndromes, including Still’s disease, and prosthetic-joint-associated infections, we refer to recent comprehensive reviews (2, 17).

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

In patients with acute arthritis, a high suspicion of septic arthritis is mandatory, because the joint can be destroyed if the treatment is postponed for a few days. Only prompt treatment can lead to restoration of normal function. Indeed, infectious etiology should be suspected as long as the cause of acute joint inflammation is not known.

Septic Arthritis

The occurrence of acute joint infection is 5-9 per 100 000 person-years (11). In adults, bacteria usually enter the joint space via circulation. Although Staphylococcus aureus is the most common causative agent (Table 1), any bacterium causing blood stream infection may also enter the joint and trigger bacterial joint inflammation. Staphylococci or streptococci cover about 91% of the infections. Gram negative organisms are more common in older patients and immunocompromised patients than in younger patients.

The patients with bacterial arthritis present with fever in 60 to 80% of cases. While most patients have mild fever, a third have temperature exceeding 39oC. Due to differences in clinical features and aetiologic agent, the two forms of septic arthritis, i.e., gonococcal arthritis and nongonococcal arthritis, are usually considered as entities of their own.

Nongonococcal Arthritis

Patients with advanced age, immune suppression due to the disease itself or immunosuppressive therapy and abnormal joint structure or joint prosthesis are in an increased risk for joint infection (Table 2).

Gonococcal Arthritis

In Europe, about 1% of septic arthritides are caused by gonococci (1). Gonococcal arthritis is 3-4 times more frequent in women compared with men. This is probably due to the asymptomatic genitourinary infection, which is more frequent in women and allows spreading of the infection. Other risk factors for gonococcal arthritis are pregnancy, menses, multiple sexual partners, low socio-economic status, intravenous drug use, complement deficiency, human immunodeficiency virus infection and systemic lupus erythematosus.

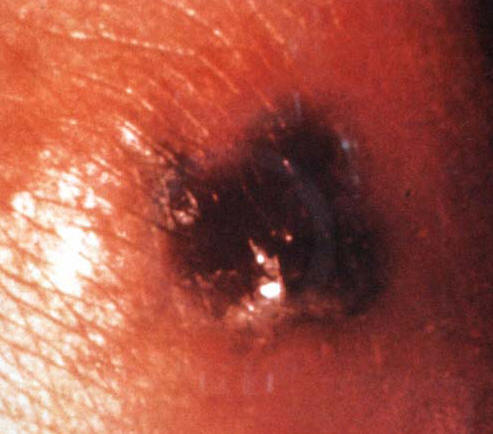

The patients often present with severe polyarthralgia, fever and chills. Skin lesions (non-pruritic, tiny papules, pustules or vesicles with an erythematous base) in the trunk or extremities occur in more than 50% of the patients (Figure 2, Figure 3). Tenosynovitis occurs also in more than 50% of the patients. Predilection is on the dorsum of hands, fingers and feet, wrists and ankles. Obviously, in some patients the clinical features may progress from a dermatitis-tenosynovitis syndrome to monoarticular joint inflammation. The diagnosis is based on the clinical picture supplemented with an evidence of gonococcal infection.

As to differential diagnosis, Neisseria meningitides infection can mimic the disseminated gonococcal syndrome. In the absence of tenosynovitis or skin lesion, the clinical features of the gonococcal may mimic those of nongonococcal septic arthritis caused for instance byStaphylococcus aureus.

Reactive Arthritis

No universal agreement of classification and diagnostic criteria are available for reactive arthritis, which was originally defined as arthritis developing soon after or during an infection elsewhere in the body, but in which the micro-organism does not enter the joint. Later on, the presence of microbial cell wall structures, DNA and even RNA have been demonstrated in the joints of the patients with typical reactive arthritis. Even knowing this, the term reactive arthritis defined as above, is useful to cover the clinical entity. Reiter’s syndrome is an old synonym for reactive arthritis. It has been especially used in US literature and often refers to a patient with chronic arthritis, especially if associated with urethritis and/or eye inflammation.

Microbes associated with reactive arthritis are Gram-negative lipopolysaccharide-containing bacteria, all intracellular pathogens. The primary focus of infection is through mucosal membrane, usually in the gut or in the urogenital tract (Table 4).

The classical microbes in the gastrointestinal tract include yersinia, salmonella, shigella, Campylobacter jejuni,and also Clostridium difficile, although less frequently. Previously,Shigella flexneriwas the onlyShigellaspecies associated with reactive arthritis, but according to a large epidemiological survey in Finland, all these species ofShigellacan trigger reactive arthritis (6). Other less frequently diagnosed infections in association with reactive arthritis are Campylobacter lari and Chlamydia psittacii. Chlamydia pneumoniae, a respiratory pathogen, is the triggering agent in about 10% of patients with reactive arthritis. Also bacteria belonging to the normal gut flora, such as Escherichia coli, have occasionally been connected with reactive arthritis.

Chlamydia trachomatis is by far the most common cause of genital infection and also the most common triggering infection for reactive arthritis. Of the other microbes causing urethritis, there is no consensus whether Neisseria gonorrhoea can trigger reactive arthritis. Infection with Mycoplasma genitalium and Ureaplasma urealyticum is connected with urethritis, but their role as an independent trigger (in the absence ofChlamydiainfection) is still discussed. The annual incidence of reactive arthritis is 10-30/100 000,Chlamydia trachomatisandEnterobacteriaeplaying an equal aetiological role.Campylobacterhas recently risen as one of the most important infection to cause gastroenteritis in Western world, whereShigellainfections are uncommon and usually imported (6).

Genetic Aspects

Genetic factors for the susceptibility can partially explain the fact that only 1-15 % of the infected subjects develop reactive arthritis. In hospital-based series, about 60-80% of the patients have HLA-B27, the presence of HLA-B27 is associated with a more severe arthritis and occurrence of extra-articular features, and it predicts a prolonged disease. In studies of defined outbreaks or in epidemiological surveys at population level, the picture is different. The disease is usually mild, oligo- or polyarticular, and there is only a slight or no increase in the frequency of the HLA-B27 antigen (10).

Pathogenesis

The classical bacteria capable to trigger reactive arthritis are gram-negative obligate or facultative intracellular aerobic bacteria with a lipopolysaccharide-containing outer membrane. They are invasive and cause primary infection of gastrointestinal mucosa (enteric pathogens) or urogenital mucosa ( Chlamydia trachomatis ). The invasiveness of the bacteria is not probably contributed by the genetic factors (HLA-B27), but there is abundance of evidence in favour of the hypothesis of an impaired elimination of the microbes in the infected host. In patients with reactive arthritis, bacterial antigens seem to disseminate in the body, and chlamydia, yersinia, salmonella and shigella antigens have been detected in the synovial fluid or in synovial tissue. Yersinia DNA and even RNA as well as chlamydial DNA and RNA have been detected by sensitive techniques in the joints, but also in some asymptomatic control persons.

After invasion via mucosal route, the microbes persist either in the epithelium or within associated lymphoid tissues, liver and spleen. The viable organisms or bacterial antigens are disseminated to the joint, causing local inflammatory response in the joint. A CD4+ T-cell response to the invading micro-organism drives the arthritic process, supported probably also by CD8+ T-cell response. There is an imbalance in the production of proinflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood mononuclear cells during acute arthritis (low TNF production). Patients with chlamydia reactive arthritis have also elevated number IL-10- and TGF-β-secreting cells in the synovial membrane compared with samples from rheumatoid arthritis patients. A deviating/poor Th2 cytokine response may favor the persistence of the microbes/microbial antigens and contribute to the poor elimination of the antigens in the host (7).

While HLA-B27 is not required for the development of reactive arthritis, its presence is contributing to the chronicity of the disease. The role of HLA-B27 in this process has been discussed, and the favorite hypothesis is a cross-reaction between microbial structures and HLA-B27, or that HLA-B27 itself might be a target of immune response. Thus, the persistence of microbial structures in the host could be explained by an impaired elimination of the microbes by deficient cytokine reaction or defective/aberrant function of HLA-B27.

Clinical Features

There is usually a delay of 1-2 weeks from the start of infection to the onset of musculoskeletal symptoms. For Chlamydia trachomatis, this period can be up to 4 weeks. The triggering infection can also be asymptomatic. The patients are usually young adults, with a mean age of about 30-40 years; in children the disease is uncommon and usually associated with gastroenteritis. Male and female patients have similar risk for the development of reactive arthritis induced by gastrointestinal infection, while reactive arthritis triggered byChlamydia trachomatisis more frequently diagnosed in male patients.

Patients have typically asymmetric oligoarthritis, often in large joints of lower extremities (Figure 4). However, about 50% of the patients have arthritis also in upper limbs. The disease can also manifest as a mild polyarticular form of arthritis in small joints. Patients can also have dactylitis (Figure 5).

The patients have frequently extra-articular inflammatory symptoms and signs (Table 5).

Enthesitis or bursitis can occur as well as other extra-articular features, common to other spondyloarthritides. They include eye symptoms (conjunctivitis, acute anterior uveitis), various skin symptoms (Figure 6), and occasionally onycholysis in prolonged or chronic cases, resembling those seen in psoriasis. About 30% of the patients have acute inflammatory low back pain, typically worse during night, radiating to buttocks.

Reactive Arthritis After Upper Respiratory Tract Infection

Streptococcal sore throat (caused by Group A beta-haemolytic streptococci) can be complicated by the development of acute rheumatic fever. Indeed, migratory polyarthritis is one of the five major manifestations of rheumatic fever (Table 6), whose diagnostic criteria (the Jones criteria) have been updated in 1992 (5).

Acute rheumatic fever can be suspected in the presence of two major manifestations, or one major and two minor manifestations, if the patient has evidence of preceding streptococcal infection, and other causes of acute arthritis have been ruled out. According to these criteria, a patient with streptococcal infection followed by arthritis as the only major manifestation, should have at least two other minor manifestations for the diagnosis. The arthritis is not associated with HLA-B27. Acute rheumatic fever is nowadays a rare disease in the developed countries, but is still a major concern in the developing countries.

There are also patients with acute mono- or oligoarthritis preceded by group A streptococcal pharyngitis as the only manifestation without other features of rheumatic fever. This so-called post streptococcal reactive arthritis usually develops within 14 days afterstreptococcal pharyngitis; fever and scarlatiniform rash are often present during the acute phase of pharyngitis, but are absent by the time the arthritis appears. Contrary to the arthritis of acute rheumatic fever, which is migratory and responds rapidly to acetosalicylic acid, the arthritis in the post streptococcal reactive form is prolonged and running the course of typical reactive arthritis. Other major manifestations of acute rheumatic fever are also absent. During a later follow-up, some of the patients have had signs of chronic rheumatic heart disease, making the diagnosis of the acute phase questionable. Poststreptococcal reactive arthritis is not a single entity but a very heterogeneous group of diseases manifesting from acute rheumatic fever to a more like HLA-B27 associated reactive arthritis without other features of acute rheumatic fever.

Finally, reactive arthritis is attributed in 10% of cases to be due to upper respiratory tract infection with Chlamydia pneumoniae. The clinical picture is that typical of that of the other reactive arthritides, here usually preceded by upper respiratory tract infection.

Lyme Arthritis

Lyme disease (Lyme borreliosis) is a tick-borne infectious disease causing complex clinical symptoms. The infection is caused byBorrelia burgdorferi (most prevalent in the USA),B. gariniiandB. afzelii. The risk of infection is variable in geographically different areas, depending on the density of infected ticks, their feeding habits and annual hosts. In Europe, Lyme borreliosis is most common in forest areas. It has spread into whole Europe, except for the most warm and dry areas in the south and the most cold areas in the north. The annual incidence of Lyme disease in the USA is 8/100 000 and in central Europe and in Scandinavia varying from 0.3 to 155/100 000 (16).

The clinical features of Lyme disease are usually divided between the duration of the disease (acute vs. chronic). This separation is often arbitrary. The history and clinical symptoms, eg. skin changes including erythema migrans in acute phase and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans in chronic phase, may help in the diagnostic work - up of a patient with musculoskeletal symptoms. The distribution of clinical features are slightly different if patients from the North America or from Europe are compared (Table 7). Severe and chronic arthritis is more frequently described in North American populations. This is probably due to geographical differences in the bacterial species.

Erythema migrans, the hallmark of the primary infection, is observed in 70% of the patients. About half of the patients develop also signs and symptoms of systemic infection (malaise, fatigue, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, low-grade fever, and lymphadenopathy). The infection also readily disseminates, at least in the US patients.

Acute neuroborreliosis develops in about 15% of the patients within weeks-months after the primary infection. Acute carditis is uncommon (in 5% of the patients). Borrelia infection can also cause eye inflammation (conjunctivitis and uveitis, most commonlyposterior uveitis).

If untreated, borrelia infection may persist for months or years. It can manifest in the skin as chronic atrophic changes, occurring in European patients and caused byB. afzelii. The patient can also have neuropathic pain and arthritis in the affected areas. Chronic neuroborreliosis is rare. It can manifest as chronic encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, peripheral neuropathy, even as cerebral vasculitis. Cognitive disturbances, radicular pain and distal paresthesias occur.

In the US, whereB. burgdorferisensu stricto (ss) is the main infecting agent, arthritis is the most common manifestation of borreliosis. The arthritis can occur early or late after the infection. The arthritis is usually mono- or oligoarticular, affecting large joints (knee, ankle, elbows). The arthritis runs a fluctuating course with remissions and relapses. Dactylitis and bursitis have occasionally described, but sacroiliitis is not a feature. Signs of systemic inflammation are usually mild, and rheumatoid factor is usually absent. Synovial fluid shows active inflammation with leukocyte counts up to 100000xE6/l, with polymorphonuclears as predominant cells.

The prognosis of Lyme arthritis is usually good; even when untreated, about 10% of patients recover/year. Erosions are rare. After appropriate antibiotic therapy, 90% of the patients do recover. A small proportion of patients do not respond to antibiotic therapy. In the US patients, about 10% belong to this group. In European patients, there are fewer such patients.

Viral Arthritis

Parvovirus

Human parvovirus B19 is a small non-enveloped DNA virus, which only replicates in erythrocyte precursors. Transmission of infection occurs via respiratory route, through blood products and vertically from mother to fetus. About half of the infections are asymptomatic. Parvovirus B19 is a common viral infection affecting predominantly children, in whom it causes erythema infectiosum(‘fifth disease’), a febrile exanthema characterized by a 'slapped cheek’ rash with or without joint symptoms. The rash is typical, and can be easily diagnosed. In adults, its manifestations are more protean (Table 8), including symptoms such as aplastic anemia,thrombocytopenia and pancytopenia. Arthritis or arthralgia occur in about 8% of juvenile and 60% of young adult patients (4). During pregnancy, the infection can cause hydrops fetalis and death of the fetus.

The arthritis is acute, symmetric, often in metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of hands. Knees, feet, wrists, ankles are also frequently involved. Coxitis is not common. The arthritis is more frequent in female than in male patients. The arthritis usually subsides within 3 weeks without permanent damage. In about 20% of the patients, usually women, the arthritis/arthralgia persist for months. Clinical suspicion is strengthened by the history of preceding rash, which, however, can be absent. If no such history can be obtained, parvovirus antibodies are not indicated in the search for triggering infection e.g. in a patient with clinical diagnosis of reactive arthritis.

The clinical picture of systemic lupus erythematosus and parvovirus infection can be very similar; furthermore, parvovirus antibodies can be produced by a patient with established systemic lupus erythematosus . However, parvovirus infection is a very rare cause of the development or flare-up of systemic lupus erythematosus.

Rubella

Rubella virus is a single-stranded RNA containing virus. The infection occurs via inhalation of airborne droplets or from mother to foetus. The most common manifestation of the infection is rash, preceded about 6 days prior by lymphadenopathy. Postinfectious encephalopathy, Guillain-Barré polyradiculitis, transient thrombocytopenic purpura and haemolytic anaemia are rare complications. Transmission of the virus to the fetus during pregnancy can lead to severe malformations.

Arthritis and arthralgia are uncommon in children and in adult male subjects, but occur in about 50% of adult females, soon after the onset of the rash. Arthritis is usually symmetric polyarthritis, most commonly in the metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints of hands, followed by wrists, knees, ankles and elbows. The arthritis usually runs for a maximum of 3 weeks and is self-limited. Sometimes, a prolonged or relapsing course can occur. Rubella infection can be prevented by vaccination by attenuated living rubella vaccines. Vaccination can also induce similar arthritis in adult females, thought to be due to immune complexes (4).

Alphavirus Arthritis

Alphaviruses belong to a group of arboviruses and share the common feature of transmission by arthropod vectors. Alphaviruses are spherical small RNA containing viruses with a potential to induce arthritis, fever, fatigue and rash. The spectrum of clinical symptoms in association with alphavirus infections is wide, from severe haemorrhagic symptoms to paresthesias and glomerulonephritis (Table 9).

The most severe form is induced by Chikungunya virus. In Northern Europe, milder forms of disease induced by alphaviruses belonging to the Sindbis group has described in several countries. In Finland, this mosquito-borne viral disease is called Pogosta disease, in Sweden Ockelbo disease, and in Russian Karelia it is called Karelia fever.

The Sindbis virus induced diseases in Northern Europe typically occur in late summer or early fall, coincident with walking in the forest during mosquito time. The incubation time is short (2-10 days), after which the onset of arthritis is usually sudden. The arthritis in Pogosta disease is often oligoarticular (ankle, knee, wrist, fingers, especially metacarpophalangeal joints). Other features are fatigue and maculopapular or morbilliform rash, often itchy. The rash, present in the majority of the patients, appears 3-4 days after the onset of illness, and disappears after a few days. Other systemic symptoms include fever, muscle pain, malaise, headache, nausea, and retro-orbital pain. Symptoms common to all alphavirus infections include rhinorrhoea, sore throat, marked lethargy and backache. The arthritis is usually transient with migratory arthralgia in the small joints of hands, feet, wrists and ankles, often accompanied by generalized myalgia. In about half of the patients the recovery from the arthritis can take more than 1 month, even for more than 12 months, but a complete recovery is the rule (9). Men and women are affected with similar frequency. Children often have subclinical infection. Some alphavirus infections affecting populations outside Europe (see Table 8) can induce petecchiae, bleeding and neurological symptoms, but the European Sindbis virus infections are milder in that sense.

HIV Infection and Arthritis

Patients infected with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection have increased frequency of musculoskeletal complaints (14). Arthralgia occurs in 5% of patients with HIV infection. The musculoskeletal symptoms can be divided in 3 subgroups: those associated directly with the HI virus infection, those occurring more frequently in HIV positive individuals, at least partially associated with increased risk of infection, and those as a result of HIV treatment.

Septic arthritis due to the usual infectious agents are not increased in HIV patients, but musculoskeletal infections caused by atypical mycobacteria are increased. Those mycobacteria most frequently causing septic arthritis or osteomyelitis include Mycobacterium avium intracellulare, M. kansasii, M. haemophilum, M. terrae and M. fortuitum (14). These induce systemic infection, and frequently infection of several joints or skeletal sites. Cutaneous lesions (nodules, ulcers, draining sinus tracts) occur frequently. These infections occur late in the course of HIV infection, as also fungal infections, which also can cause septic arthritis.

HIV infection is associated with arthritis which is resembling other viral arthritides. It is typically oligoarticular, predominantly in the lower extremities, and lat lasts less than 6 weeks. The synovial fluid, if obtained for analysis, is non-inflammatory and sterile for bacteria. There is no increased association with HLA-B27. The arthritis is usually self-limiting, and can be treated with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). In the more severe arthritis, low-dose glucocorticoids, hydroxychloroquine or sulphasalazine can be used. Infective joint complications are also frequently observed in the African AIDS patients, while AIDS is the leading cause of aseptic arthritis (60% of the cases). Most of the patients have aseptic polyarthritis, the rest have oligoarthritis. The arthritis is symmetrical and nonerosive, with predilection to large joints in the lower extremities.

The incidence of HIV-associated reactive arthritis is increased. The clinical picture is typical to reactive arthritis with oligoarticular pattern, enthesitis, and sausage toes/fingers. Mucocutaneous complications (keratodermia blenorrhagica and circinate balanitis) are common. The disease is associated with HLA-B27. Reactive arthritis is observed in 5-10% and psoriatic arthritis in 1-6% and undifferentiated spondyloarthritis in 3-11 % of the patients. There are differences in clinical features in the phenotypes of arthritides between African patients with AIDS and the Western patients, those in Western having more typically reactive arthritis. In the pathogenesis of arthritides, both direct spreading of the HI-virus to the joints, immune response of the host to the infection, and infection of the host with pathogens known to be capable to trigger reactive arthritis especially in HLA-B27 positive subjects (Chlamydia, salmonella, yersinia, shigella, campylobacter) contribute to the development of arthritis.

Previously, HIV infected patients often developed severe psoriasis-like skin disease and also psoriatic arthritis. The use of highly active anti-retroviral therapy (HAART) is effective in the treatment of the HIV infection and also the associated psoriasis and arthritis.

The availability of HAART has made a great change in the prognosis of the patients infected with HIV. However, musculoskeletal symptoms are very common. Diffuse myopathy, muscular pain, elevated muscle enzyme levels, even rhabdomyolysis, and avascular necrosis of bone have been reported with increasing frequency on patients treated with antiviral drugs. These adverse events have been linked with various therapies, especially protease inhibitors. At the same time, there has been a great shift in the diagnoses compared with historical data. Infectious complications have been in increase. In addition, malignant complications (non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma) have been more frequently observed, while reactive arthritis and psoriatic arthritis have been decreasing.

Hepatitis C Virus and Arthritis

Hepatitis C infection is globally infecting about 2% of the population. The lowest prevalence rates (0.01% to 0.1%) are from United Kingdom and Scandinavian countries, and the highest from Egypt (15% to 20%). After the acute phase, 50%-70% of the patients develop chronic infection, which is a risk factor for future development of liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. In addition to causing hepatitis, hepatitis C virus is lymphotropic and has been associated with the induction of various autoantibodies and immunologic entities. Hepatitis C infection has been associated with vasculitis, either associated with cryoglobulinaemia or a polyarteritis nodosa-like vasculitis. Other rheumatologic/immunological associations include Sjögren’s syndrome, glomerulonephritis, thyroiditis, neuropathy, pulmonary fibrosis, myositis, and thromboembolic phenomena with anti-cardiolipin antibodies (15).

Musculoskeletal pain (myalgia, arthralgia, arthritis) is common among the patients. Arthritis is reported in 2-20% of patients with hepatitis C. The arthritis has two different patterns. The more common is polyarthritis, often mimicking rheumatoid arthritis, which involves small joints (metacarpophalangeal joints, wrists, ankles). Simultaneously, also large joints can be affected. The patients often are seropositive for rheumatoid factor. More than 50% fulfill the current classification criteria for rheumatoid arthritis. Compared with rheumatoid arthritis, the arthritis in patients with hepatitis C virus infection, despite often being seropositive for rheumatoid factor, is more benign, not erosive, with fluctuating activity. The less common form of arthritis is mono- or oligoarthritis, usually in larger joints (wrists, shoulders, ankles, knees) but without features of spondyloarthropathy. Synovial fluid is inflammatory. Hepatitis C RNA has been detected in synovial fluid.

Circulating cryoglobulins are present in less than half of the patients, sometimes associated with purpura, livedo reticularis, glomerulonephritis, peripheral neuropathy, or Raynaud phenomenon, i.e., symptoms typical of vasculitis. The presence of the cryoglobulins and the clinical associations speak in favor of the hepatitis C as the background cause of arthritis. About one third of the patients have normal liver enzymes. Thus, the presence of normal liver enzymes in laboratory screening does not rule out the possibility of hepatitis C virus infection. In more than two thirds of the patients there are risk factors for acquisition of hepatitis C in the history, such as blood transfusion, use of injected drugs, or tattooing. Although most patients have circulating rheumatoid factor, anti-CCP-antibodies are usually negative.

Hepatitis C virus infection is associated with mixed cryoglobulinaemia. This is responsible for the vasculitis type of symptoms. The cryoglobulins form immune complexes and could be responsible for arthritis at least in a part of the patients. However, not all patients with arthritis have cryoglobulins. The hepatitis C virus itself has been found in the synovial fluid cells, taken as an indicator of direct infection. Furthermore, the persistence of hepatitis C virus in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells could induce chronic antigenic stimulation, especially in the long-living B-cells, and thus induce imbalance in the immune system leading to chronic B-cell activation and immune-mediated disorders, including arthritis. Both the Th1 and Th2 cytokines are elevated in the sera of the patients, which can further propagate the inflammatory aberration and autoimmune phenomena.

Hepatitis B Virus

Polyarticular arthritis or arthralgia, which affects mainly small joints of the fingers, may occur in about 20% of the patients with acute hepatitis B virus infection. The joint symptoms last 2 to 3 weeks and gradually resolve when the patients starts to turn yellow. Arthritis often accompanied by rash. The disorder is considered to be mediated by circulating immune complexes.

Crystal-Related Arthritis

Gout, an inflammatory response to monosodium urate monohydrate crystals and pseudogout (chondrocalcinosis), an inflammatory response associated with calcium pyrophosphate crystal deposition are the major forms of crystal-related joint inflammation.

Acute gout develops within hours and is designated by intense pain, swelling and redness of the affected joint (Figure 7), and often by fever ascribed to spill-over of pro-inflammatory cytokines from the inflamed joint into the circulation. Of the initial attacks, about 90% are monoarticular and about 50% affect the first metatarsophalangeal joint. In time, this joint is affected in about 90% of the patients. Although gout may affect any joint, in general, the lower limbs are affected more often than the upper limbs. Without treatment, mild attacks resolve within a couple of days, severe attacks usually within a week. Occasionally, the patient presents with monoarthritis and high fever suggestive of sepsis, or he/she presents with polyarthritis suggestive of other arthropathies. Particularly in the elderly, polyarthritic gout with low degree inflammatory reaction to urate crystals may be regarded as a type of osteoarthritis. The gout attacks can be precipitated by a variety of factors such as drugs which alter the circulating urate levels, dietary factors (wines, beer, fish skin, meat) and trauma including surgery. Finally, urate crystals may be considered as foreign bodies which render the joint susceptible to bacterial infections.

Pseudogout also presents in 90% of cases as monoarthritis, but unlike in gout, the knee is the most common affected joint, followed by the wrist, shoulder, ankle and elbow. Like in gout, the onset of the attack is rapid, the affected joint is tender, warm, red and swollen and functionally impaired, and the presence of fever is common. Most of the attacks develop spontaneously and take slightly longer than gout to resolve, 1 to 3 weeks, if not treated.

Sarcoid Arthritis

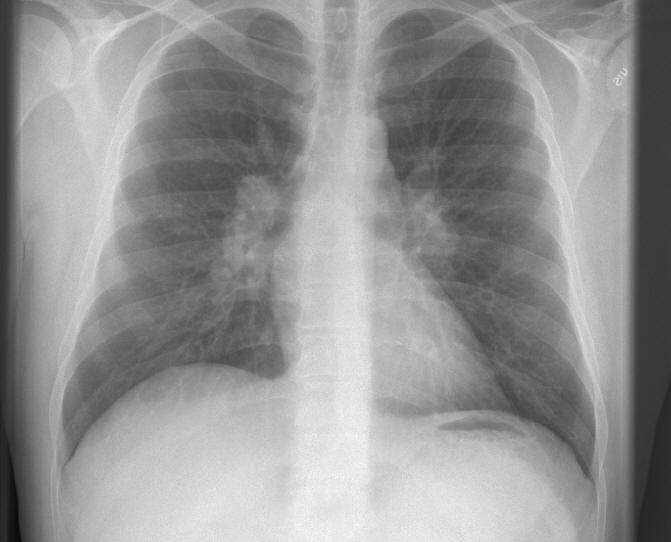

In sarcoid arthritis, a non-caseating granulomatous inflammation affects the joint tissue, most commonly the ankles and the knee joints and less frequently other larger joints such as shoulders, hips, wrists, elbows or small joints of the hand and feet. Although the joints are usually affected bilaterally, they may be affected asymmetrically in a consecutive manner. The affected joints show tenderness with effusions, limitation of movement and often prominent periarticular swellings. Extra-articular manifestations of sarcoidosis are common and include the presence of erythema nodosum nodules usually in the lower limbs (Figure 8) and bilateral hilar lymphadenopathy in chest radiology (Figure 9). This form of acute sarcoid arthritis, also called Löfgren's syndrome, is common in Scandinavian countries. A patient with acute sarcoid arthritis can also have fever and elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP); rheumatoid factor can also be positive. The prognosis of acute sarcoid arthritis is usually good. The patient usually recovers within 2 weeks to 4 months, even if untreated. Chronic sarcoid arthritis is less common, and is more prevalent in the black population. It is a late manifestation of systemic sarcoidosis and is associated with chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis or other forms of systemic sarcoidosis, such as chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis /lupus pernio). The patients can have a mild, transient, recurrent or chronic polyarthritis. The disease can mimic rheumatoid arthritis; although usually milder than rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatoid factor can be positive, which can furthermore confuse the diagnosis.

Paraneoplastic Arthritis

Paraneoplastic joint inflammation presents usually as a polyarthritis, often asymmetric arthritis with predilection to joints of the lower limbs. It can be suspected in an elderly patient with acute asymmetric arthritis and markedly elevated ESR and CRP. It may precede the diagnosis of the malignancy in the lung or the breast and may resolve after resection of the carcinoma. Unlike paraneoplastic arthritis, the metastatic joint inflammation is usually monoarticular reaction in large joints, such as the hip and knees.

Clinical Approach to Diagnosis

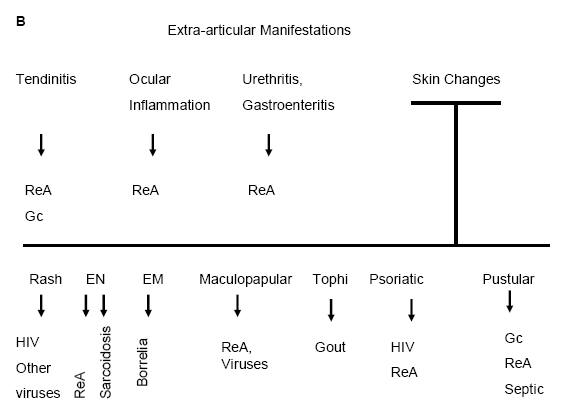

The clinical features may be suggestive for the final diagnosis of a patient who presents with fever and acute arthritis (Figure10). Although not specific for any of the underlying pathomechanisms, they may be helpful, together with patient’s history and family history of rheumatic disorder, in selecting diagnostic laboratory tests, imaging, and selecting initial therapy.

LABORATORY DIAGNOSIS AND IMAGING

Septic Arthritis

In the suspicion of septic arthritis, arthrocenthesis of the joint is mandatory, and the synovial fluid is aliquoted for analysis of WBC count, differential and Gram stain, and for culture of bacteria. The concentration of WBC in the synovial fluid is usually increased, and a count of >50 000 xE6/l with >90% of polymorphonuclears increases the likelihood of septic arthritis. Blood samples are collected for culture of bacteria. Laboratory markers of systemic inflammation (increased WBC count, ESR and CRP) have only a limited diagnostic value due to their insensitivity. A markedly elevated CRP (>100 mg/l) increases the likelihood of septic arthritis only slightly, by a likelihood ratio of 1.6. Radiography of the joint is usually normal, unless there is a chronic rheumatic condition (rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis etc), but it is worth to study to exclude the possibility of underlying osteomyelitis.

Gonococcal cultures of the urethra/cervix, rectum and oropharynx should be performed and are positive in about 80% of the cases. Blood culture is positive in less than 50% of the patients. Joint aspiration is positive in about 50% of the cases; bacterial cultures of the skin lesions are usually negative. Contact tracing and cultures of the partners can help in the diagnosis (1).

Patients with gonococcal arthritis can have elevated WBC in the blood, and elevated ESR and CRP. Synovial fluid shows inflammatory pattern. Ligase chain reaction and polymerase chain reaction are available for the detection of nucleic acid sequences specific forN. gonorrhoeain urogenital samples, first-void urine, or synovial samples. Cultures are preferred because of the microbial sensitivity pattern can also be determined. Serological tests perform less well.

Reactive Arthritis

The diagnosis of reactive arthritis relies, besides to the typical clinical picture, on demonstration of the triggering infection, such as isolation of the microbe or demonstration of elevated antibodies. During the acute phase of enteric infections isolation is usually possible from the stools. However, by the time arthritic complications appear, the patient may have already recovered from the gastroenteritis and the microbe is often no longer detectable, and the laboratory diagnosis is often dependent on the serodiagnosis. Unfortunately there are no international standards for the tests, and the techniques vary greatly (6).

The use of serology for the diagnosis of infections with Chlamydia trachomatis is hampered by a relatively high prevalence of positive antibodies among normal population and by a possible cross-reactivity with antibodies directed against Chlamydia pneumoniae. Determination of IgG antibodies is not sufficient, but these should be combined with tests for IgM and IgA antibodies. Positive serology alone without a history of a urogenital tract infection does not suffice to make a definite diagnosis ofChlamydia-induced reactive arthritis. Most of the genital infections are asymptomatic. Therefore, a high suspicion forChlamydiaat the background is relevant for the diagnosis of reactive arthritis with tests to detect ofChlamydia trachomatisin the urogenital tract. Search forChlamydiain the first portion of the morning urine by ligase reaction seems to be the test-of-choice. It is more convenient and the results are comparable with that by urogenital swab.

In about 60% of the patients with reactive arthritis, evidence of previous infection can be detected either by serology or by cultures from urogenital or stool samples.

Based on hospital series, the occurrence of HLA-B27 has been reported to be as much as 90% but is considerably lower or not elevated at all if patients with mild arthritis is examined. Therefore, the use of HLA-B27 as a diagnostic tool is disputed. If the clinical picture is not strongly favoring reactive arthritis, the post-test possibility of the use of HLA-B27 in the diagnosis is low.

ESR and CRP are usually elevated. Synovial fluid leukocyte count is between 2000-60000xE6/l. Other rheumatic conditions, such as Lyme arthritis, gout, rheumatoid arthritis, viral arthritides and osteoarthritis, should be excluded on the basis on clinical picture.

Lyme Arthritis

Serology does help in the decision making in the more complicated disease. Borrelia antibodies of IgM class start to rise 2-4 weeks after infection, peaks within 6-8 weeks after which the production is switched to IgG class. IgM and IgG class antibodies can persist in some patients for many years, even after therapy. A highly sensitive ELISA test should be used in screening, and the result confirmed by an immunoblot test. Especially in European patients, the test should cover all the relevant species (B. burdorferi ss, B. afzelii, B. garinii). After clinically successful therapy, there is no need to control the antibody levels.

Culture of the borrelia in skin biopsy and in plasma can be performed, but the culture is rarely successful from the synovial fluid. Borrelia DNA has been detected by PCR in skin biopsies, cerebrospinal fluid, synovial fluid, blood and urine. It is not a routine method, but can be used as an aid in the differential diagnosis of synovitis. The detection of borrelia by PCR is highly specific, but the sensitivity in the synovial fluid is max 85%.

Viral Arthritis

Parvovirus Arthritis

The diagnosis of parvovirus infection is made by serology, where the presence of IgM class parvovirus antibodies refer to a recent infection within 3 months. As most people have acquired parvovirus infection in the childhood, the presence of IgG class antibodies is common and in the absence of IgM class antibodies is not of diagnostic aid. The patients can be transiently seropositive for rheumatoid factor, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies as well as have various auto-antibodies which can make differential diagnosis between parvovirus arthritis and other arthritides very complicated. Parvoviral B19 DNA has been detected in synovial fluid samples in some patients with early synovitis or with chronic rheumatoid arthritis.

Rubella Arthritis

The routine laboratory diagnostics of rubella infection is based on the detection of antirubella antibodies in the serum. Detection of antirubella IgM in combination with IgG seroconversion or detection of a rise in rubella-specific IgG in paired sera indicates acute infection. Recent primary rubella, remote rubella infection, reinfection and persistent rubella IgM reactivity may be differentiated by measuring rubella-specific IgG avidity (4).

Other Viral Arthritides

The diagnosis of alphavirus infection is based on history (travelling in tropical areas, walking in forests in summer/early autumn), on clinical picture (rash and arthritis) and confirmed by serology. The diagnoses of infections cause by HIV, hepatitis C virus, or hepatitis B virus are based on serology and PCR techniques.

Crystal-Related Arthritis

The diagnosis is based on demonstration of crystals, sodium urate crystals in gout and calcium pyrophosphate crystals in pseudogout, in synovial fluid samples using polarized microscopy. Hyperuricaemia is a risk factor for the gout, and the risk increases along with the increase in urate levels. Although hyperuricaemia is prerequisite of, it is not sufficient for the development of gout because many hyperuricaemic subjects never develop gout.

Sarcoid Arthritis

The diagnosis of acute sarcoid arthritis is based on typical clinical picture (marked periarticular swelling of ankles bilaterally and hilar lymphadenopathy), further supported if erythema nodosum is observed. Frequently the patient has elevated ESR and CRP. The laboratory markers of sarcoidosis (elevated serum ACE and lysozyme levels, hypercalcaemia and –calciuria) can be positive, but less often than in chronic systemic sarcoidosis. Patients with chronic sarcoid arthritis can also have positive serology for rheumatoid factor. Musculoskeletal radiology of acute sarcoid arthritis is normal, contrary to that in chronic sarcoid arthritis, where in addition to unspecific signs of inflammation (periarticular swelling, less frequently periarticular osteoporosis), cysts in finger and toe bones can be occasionally seen.

Paraneoplastic Arthritis

The acute onset of seronegative asymmetric polyarthritis with markedly elevated inflammatory markers should raise the suspicion of cancer polyarthritis. In most patients, the condition is associated with breast cancer.

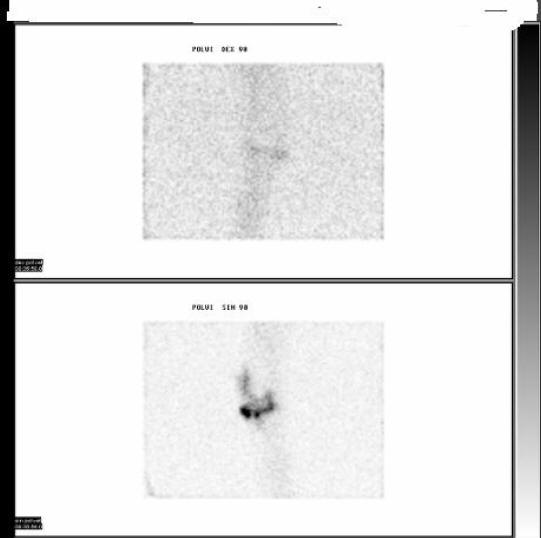

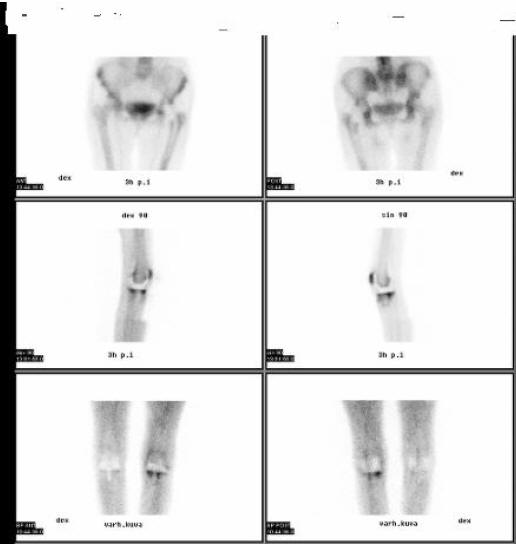

Imaging plain radiographs should be performed as the initial imaging procedure. They provide useful information of the pre-existing condition of the joints, such as bone erosions associated with rheumatoid arthritis or bone cysts associated with chronic sarcoid arthritis. Acute sarcoid arthritis is frequently associated with bilateral hilar lymph node enlargement. New radiographic bone changes become evident only a couple of weeks after the onset of joint infection (Figure 11, Figure 12). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reveals changes before radiography, is useful in evaluation of the joint and its bony structures, and is superior to computed tomography in evaluation of soft-tissue changes. Bone scintigraphy, performed for instance with technetium-99m-labeled diphosphonates, may not distinguish between aseptic arthritis, septic arthritis, and osteomyelitis (13). Finally, imaging with leukocytes labeled with indium-111 (Figure 13) or technetium-99m do not reliably separate infectious arthritis from non-infectious arthritides, such as rheumatoid arthritis, gouty arthritis, and pseudogout. If leucocyte labeled scan is positive, a three-phase bone scan with technetium-99m labeled diphosphonates can be used in the confirmation of osteomyelitis, where focal hyperperfusion, focal hyperemia, and focal bone uptake is observed (13) (Figure 14).

OUTLINES OF EMPIRIC ANTIBIOTIC THERAPY IN SUSPECTED SEPTIC ARTHRITIS

The treatment includes arthrocenthesis with removal of any purulent material from the joint and institution of systemic antibiotic therapy before the results of the bacterial cultures are available. The choice of the antibiotic is primarily empirical and based on the likelihood of the organism involved (Table 10). When the culture results are available, the antibiotics can be focused according to the sensitivity results. The duration of the intravenous therapy can be 10-14 days, often followed by oral antibiotics. The total duration of treatment is depending on the infecting micro-organism, the other diagnosis and therapies, and on the initial response to the treatment.

OTHER THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS

Septic Arthritis

The drainage of the inflammatory debris is beneficial for the preservation of the joint function and limiting the joint destruction. This can be performed as daily needle aspiration, arthroscopic debridement with lavage, open lavage or arthrotomy with synovectomy. There are no randomized studies that could show the superiority of any of these interventions. In practice, if a joint is easily accessible by needle arthrocenthesis, this approach can be used provided that the clinical effect is observed. In a complicated case or a joint with limited access (e.g. hip joint), arthroscopic or open lavage would probably give a better therapeutic effect. The initial treatment of gonococcal arthritis is a third-generation cephalosporin, e.g. ceftriaxone 1 g once a day (Table 10). If the microbe is sensitive to penicillin, the therapy can be switched to G-penicillin 10 million IU/day i.v. in divided doses. In the case of penicillin allergy, spectinomycin 2 g i.v. twice a day can be given. The arthritis responds very quickly to antibiotic treatment. This can be used even as a diagnostic test in a patient with typical clinical picture but negative cultures.

Reactive Arthritis

The use of NSAIDs, often with a full dose, are usually of major benefit. Local glucocorticoid injections can be applied and are usually also of benefit in the patients with mono- or oligoarticular disease, as is usually the case. Entesopathy also responds to local corticosteroid injections. Systemic use of corticosteroids are indicated if the patient is bedridden due to severe polyarthritis, there is high systemic inflammation, the patient is febrile, or if the patient has carditis/atrioventricular conduction disturbances. The patients seem to need higher doses of systemic prednisone/prednisolone, often needing a dose 20-40 mg/daily at start. For spinal pain, drugs with high anti-inflammatory effect and long half life are preferred by the patient. In the case of severe arthritis of large joints with progressive symptoms, the use of disease modifying antirheumatic drugs used in rheumatoid arthritis, can be considered. Sulphasalazine, when started during the first 3 months, can induce clinical remission more rapidly compared with placebo.

All patients with acute Chlamydia trachomatis infection should receive the routine treatment (e.g. azithromycin 2 g as single therapy, with partners treated as well). The use of antibiotics in the treatment of the arthritis is not effective. Uncomplicated enteritis preceding reactive arthritis is not an indication for treatment with antimicrobials. However, if a patient has a past history of reactive arthritis, the option for treatment of also uncomplicated enteritis may be clinically justified.

Lyme Arthritis

Lyme borreliosis is treated with antibiotics, the use of which is tailored to the clinical picture of the disease. Positive serology in an asymptomatic patient is not an indication for antibiotics. For arthritis, first choice is doxycyclin 200 mg/day for 30 days. Alternative choice is amoxicillin 500-750 mg 3 times/day for 30 days. In the case of failure of previous treatment, ceftriaxone 1 g twice a day i.v. for 14-21 days are recommended. Alternative choices are cefotaxime 2 g 3 times a day i.v. or penicillin G 5 million units 4 times a day, for 14-21 days (16).

Viral Arthritis

Parvovirus Infection

Erythema infectiosum does not usually require any treatment. The arthralgia/arthritis can been treated with NSAIDs, if severe. The prognosis is usually good.

Rubella Arthritis

The arthritis is usually short-lived and can be managed by symptomatic drugs, e.g. by NSAIDs. In the rare case of persistent rubella arthropathy, intravenous immunoglobulin therapy may be effective.

Alphavirus Arthritis

Treatment is symptomatic, but acetosalicylic acid is to be avoided if there is a suspicion of a hemorrhagic disease.

HIV Arthritis

The treatment is following the lines of that for reactive arthritis in general, starting with NSAIDs. In the more severe or prolonged disease, sulphasalazine is the recommended drug, but hydroxychloroquine can also be tried. Methotrexate, due to its immunosuppressive effect, might in theory enhance the HIV load, but can be used if viral load and the number of CD4 positive cells are monitored. Skin lesions in reactive arthritis and psoriatic arthritis, another form of arthritis observed in HIV infected patients, responds also to etretinate (14). While the biological drugs are not officially recommended and indicated for HIV related diseases, there are some case reports on the use of TNF-blocking agents in the patient with severe arthritis/skin disease, with good clinical response and without any major increase in the risk of infections or progression of immunosuppression in the patients in the short term.

Hepatitis C Virus Arthritis

If there are no contraindications for the use of antiviral therapy, this is logical to start. Currently, the use of pegylated interferon alpha (IFN) with ribavirin is recommended. Successful treatment of the infection can lead to recovery from the arthritis in the majority of the patients. The resolution of the arthritis may take up to 4 months. If the arthritis persists/there are contraindications for antiviral therapy, use of conventional antirheumatic drugs (with careful monitoring of the liver enzymes for the increased toxicity risk) can be applied, often with low dose corticosteroids (15). There are single reports of the use of anti-TNF drugs safely without the induction of increased viral load or increases in serum aminotransferase levels.

Crystal-Related Arthritis

The acute attack of gout is treated with NSAIDs. In addition, dietary advice to avoid food/beverages that induce increase in serum urate levels (see above) is part of the therapy. The used of diuretics can also induce hyperuricaemia and gout, the indications should be reviewed and, if possible, the doses should be reduced of the drug should be changed. Recurrent gouty arthritis is an indication to therapy with allopurinol; it should be started first after the acute attack is resolved. Pseudogout is treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. There is no specific drug to suppress the crystals of calcium pyrophosphate to accumulate in the joints. Causes of chondrocalcinosis should be searched (hyperparathyroidism, haemochromatosis) and treated accordingly.

Sarcoid Arthritis

Acute sarcoid arthritis is a benign disease. The joint symptoms respond to NSAIDs. If the patient is febrile, use of oral prednisolone, with starting dose e.g. 20 mg/day, rapidly reduces the symptoms. The patient has to be referred to pulmonlogists examination for the extension of lung involvement. The long-term treatment is dependent on the possible lung disease.

Paraneoplastic Arthritis

The arthritis is treated symptomatically, starting with NSAIDs. Is severe, low-dose oral prednisone/prednisolone is usually of benefit. The search and treatment of the background malignancy usually relieves the arthritis.

PREVENTION AND ANTIBIOTIC PROPHYLAXIS

Septic Arthritis

The patients with chronic joint disease are at increased risk of developing bacterial arthritis. The risk factors include the presence of knee or hip prosthesis, rheumatoid arthritis, comorbidity (malignancy, diabetes mellitus) and age of 80 years or over. In a patient carrying one or more of the risk factors, the use antimicrobial prophylaxis, in terms of bacterial arthritis, seems to be indicated in patients with dermal infections, or infections of the urinary and respiratory tracts (8). In practice, this means treatment of the patient, for instance, with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, which covers the majority of the bacteria causing purulent arthritis, with a dose of 3x500/125 mg a day orally for 10 days. For invasive dental treatment, a once only dose of 3000/750 mg orally, and for invasive medical procedures a single dose of 2000/200 mg intravenously before the treatment would be appropriate.

Reactive Arthritis

The primary prevention of acute rheumatic fever is based on adequate (10 days or over) antimicrobial treatment of tonsillopharyngitis caused by group A beta-haemolytic streptococcal infection. Penicillin is the drug of choice. In the secondary prevention, the duration of antimicrobial prophylaxis depends on several factors, such as the risk of exposure to streptococcal infections and the age of the patient (3). In the case of HLA-B27-associate reactive arthritis, it is possible, although no controlled studies exist, that early treatment of the triggering infection with antibiotics might prevent the development of arthritis. During the ongoing arthritis, however, the introduction of antibiotics does not modify the course of the disease.

Viral Arthritis

Rubella may be prevented by vaccination. At present, no vaccine exist against alphaviruses and prevention is based on using mosquito repellents, bed nets and appropriate clothing at endemic areas.

REFERENCES

1. Bardin T. Gonococcal arthritis. Best practice & research. Clinical rheumatology 2003;17: 201-208. [PubMed]

2. Church LD, Cook GP, McDermott MF. Primer: inflammasomes and interleukin 1beta in inflammatory disorders. Nature clinical practice. Rheumatology 2008;4: 34-42. [PubMed]

3.Dajani A, Taubert K, Ferrieri P, Peter G, Shulman S. Treatment of acute streptococcal pharyngitis and prevention of rheumatic fever: a statement for health professionals. Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, the American Heart Association. Pediatrics 1995;96(4 Pt 1): 758-764. [PubMed]

4. Franssila R, Hedman K. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Viral causes of arthritis. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006;20: 1139-1157. [PubMed]

5. Guidelines for the diagnosis of rheumatic fever. Jones Criteria, 1992 update. Special Writing Group of the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease of the Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young of the American Heart Association. JAMA: The journal of the American Medical Association 1992;268: 2069-2073. [PubMed]

6. Hannu T, Inman R, Granfors K, Leirisalo-Repo M. Reactive arthritis or post-infectious arthritis? Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006;20: 419-433. [PubMed]

7. Hill Gaston JS, Lillicrap MS. Arthritis associated with enteric infection. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2003;17: 219-239. [PubMed]

8. Krijnen P, Kaandorp CJ, Steyerberg EW, van Schaardenburg D, Moens HJ, Habbema JD. Antibiotic prophylaxis for haematogenous bacterial arthritis in patients with joint disease: a cost effectiveness analysis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2001;60: 359-366.[PubMed]

9. Laine M, Luukkainen R, Toivanen A. Sindbis viruses and other alphaviruses as cause of human arthritic disease. Journal of internal medicine 2004;256: 457-471. [PubMed]

1 0. Leirisalo-Repo M. Reactive arthritis. Scandinavian journal of rheumatology 2005;34: 251-259. [PubMed]

1 1. Margaretten ME, Kohlwes J, Moore D, Bent S. Does this adult patient have septic arthritis? JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association 2007;297: 1478-1488. [PubMed]

12. Mathews CJ, Kingsley G, Field M, Jones A, Weston VC, Phillips M, et al. Management of septic arthritis: a systematic review. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2007;66: 440-445. [PubMed]

1 3. Palestro CJ, Love C, Miller TT. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Imaging of musculoskeletal infections. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006 Dec;20(6): 1197-1218. [PubMed]

14. Reveille JD, Williams FM. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Rheumatologic complications of HIV infection. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006;20: 1159-1179. [PubMed]

15. Rosner I, Rozenbaum M, Toubi E, Kessel A, Naschitz JE, Zuckerman E. The case for hepatitis C arthritis. Seminars in arthritis and rheumatism 2004;33: 375-387. [PubMed]

16. Schnarr S, Franz JK, Krause A, Zeidler H. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Lyme borreliosis. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006;20: 1099-1118. [PubMed]

17. Zimmerli W. Infection and musculoskeletal conditions: Prosthetic-joint-associated infections. Best practice & research.Clinical rheumatology 2006;20: 1045-1063. [PubMed]

Tables

Table 1: Bacteria Which Are Most Commonly Isolated from Synovial Fluid of Patients with Bacterial Arthritis*

Gram-positive strains

Staphylococcus epidermidis, andother coagulase negative staphylococci

Streptococci

Gram-negative strains

* Any strain, including anaerobes, which causes bacteraemia may invade joint tissues and elicit bacterial arthritis

Table 2: Risk Factors for the Development of Septic Arthritis

Old age (>80 years)

Rheumatoid arthritis

Immunosuppressive therapy

Prosthetic joint

Previous intra-articular corticosteroid injection

Diabetes mellitus

Osteoarthritis

Low socioeconomic status

Alcoholism

Cutaneous ulcers

Trauma penetrating into the joint

Table 3: Differential Diagnosis for Acute Monoarthritis

Gout

Pseudogout

Rheumatoid arthritis

Apatite-related arthropathy

Reactive arthritis

Transient synovitis of the hip

Pigmented villonodular synovitis

Hemarthrosis

Neuropathic arthropathy

Osteoarthritis

Intra-articular injury (fracture, meniscal tear, osteonecrosis)

Metastatic carcinoma

Table 4: Bacterial Infections Associated with the Development of Reactive Arthritis

Enteritis caused by

Salmonella

Various serovars

S. flexneri

S. dysenteriae

S. sonnei

Yersinia

Y. enterocolitica (especially O:3 and O:9)

C. coli

Urethritis caused by

Upper respiratory infection caused by

Group A beta-haemolytic streptococcus**

* causes urethritis, but the role in reactive arthritis still discussed;

** typically causes acute rheumatic fever, but has been described to cause ‘reactive-like’ arthritis

Table 5: Clinical Features of Reactive Arthritis in Hospital Series

Number of joints, range |

1-24 |

Low back pain, range (%) |

2-67 |

X-ray sacroilitis, range (%) |

11-20 |

Urethritis, mean, range (%) |

4-93 |

Conjunctivitis, range (%) |

6-78 |

Iritis, range (%) |

6-17 |

Skin lesions, range (%) - erythema nodosum - pustules - keratodermia |

4-14 |

Duration of arthritis, range, months |

1-30 |

Chronic course (>12 months), range (%) |

0-30 |

HLA-B27 + , range (%) |

0-94 |

Table 6: Revised Jones Criteria for Acute Rheumatic Fever [8]

Major manifestations |

Minor manifestations |

Laboratory findings |

|---|---|---|

Carditis Polyarthritis |

Fever Arthralgia |

Elevated acute-phase reactants: a) C-reactive protein (CRP) b) Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) |

Chorea |

Previous rheumatic fever or rheumatic heart disease |

Prolonged P-R interval in ECG |

Erythema marginatum Subcutaneous nodules |

Supporting evidence of preceding streptococcal infection: a) Increased ASO or other streptococcal antibodies b) Positive throat culture for Group A-haemolytic streptococci c) Recent scarlet fever |

Table 7: Musculoskeletal Features of Borreliosis with Respect to Geographical Areas. Adapted from [9]

Clinical symptom |

Europe and Asia (B. afzelii, B. garinii, B. burgdorferi ss) |

North America (B. burgdorferi ss) |

|---|---|---|

Arthritis, acute |

Oligoarthritis (less frequent) Less intense joint inflammation |

Oligoarthritis (more frequent) More intense joint inflammation |

Arthritis, chronic |

Persisting arthritis less frequent |

Treatment-resistant arthritis in about 10% of the patients |

Table 8: Arthritis and Autoimmune Diseases Associated with Parvovirus B19 Infection

Type of arthritis |

Other autoimmune features |

Other manifestations |

|---|---|---|

Acute Chronic |

Vasculitis Antiphospholipid syndrome SLE |

Rash, haematological changes, hepatitis, myocarditis, myositis, CNS symptoms |

SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; CNS, central nervous system

Table 9: Alphaviruses Related to Articular Symptoms. Adapted from [11]

Virus |

Clinical features |

Epidemiological area |

|---|---|---|

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, rash, myalgia, chronic joint pain, haemorrhagic symptoms, paresthesias |

Africa, India, South East Asia, Philippines |

|

Mayaro |

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, chronic joint pain, rash, myalgia, haemorrhagic symptoms |

Trinidad, Surinam, Brazil, Colombia, Bolivia |

O’nyong-nyong |

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, chronic joint pain, rash, myalgia, haemorrhagic symptoms, paresthesias |

Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania, Malawi, Senegal |

Barmah Forest |

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, rash, myalgia |

Australia |

Igbo Ora |

Fever, arthralgia, rash, myalgia |

Ivory Coast |

Ross River |

Fever, polyarthritis, chronic arthralgia, rash, paresthesias, glomerulonephritis |

Australia, New Guinea, Fiji, The Solomon Islands, American Samoa, South pacific Islands |

Sindbis |

Fever, rash, arthralgia/arthritis, paresthesias |

Europe, Africa, Australia, Asia, Philippines |

Ockelbo |

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, rash, chronic joint pain, paresthesias |

Sweden, Norway |

Pogosta |

Fever, arthralgia/arthritis, chronic arthritis, rash, |

Finland |

Karelian fever |

Fever, arthralgia, rash |

Russia |

Table 10. Antibiotic Treatment of Septic Arthritis. Adapted from [4,16]

Patient group |

Antibiotic choice |

|---|---|

No risk factors for atypical organism |

Staphylococcal penicillin (e.g. cloxacillin or flucloxacillin) 2 g four times a day i.v. Fusidic acid 500 mg three times a day p.o, or gentamicin i.v. may be added. In the case of penicillin allergy, clindamycin 450-600 mg for times a day, or 2ndor 3rd generation cephalosporin may be given |

High risk of Gram negative sepsis |

2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporin (e.g. cefuroxime 1.5 g three times a day). |

MRSA (methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus) risk |

Vancomycin plus 2nd or 3rd generation cephalosporin |

Suspected gonococcus or meningococcus |

Ceftriaxone 1 g once a day (im. or iv) or similar drugs, depending on local policy/resistance |

I.V. drug users |

Discuss with microbiologist |

Intensive therapy unit patients, known colonization of other organs |

Discuss with microbiologist |

Figure 1: Septic Arthritis

Figure 2: A Pustule at Early Phase of Disseminated Gonococcal Infection

Figure 3: A Pustule With Necrotic Centre In A Patient With Disseminated Gonococcal Infection

Figure 4: Fulminant Knee Synovitis In A Patient With Reactive Arthritis

Figure 5: Dactylitis Of Left 2. Toe And Right 4. Toe In A Patient With Reactive Arthritis

Figure 6: Skin Lesions In A Patient With Reactive Arthritis Due To Salmonella Infection

Figure 7: A Patient With Acute Gouty Arthritis In The Foot

Figure 8: Erythema Nodosum

Figure 9: Bilateral Hilar Lymphadenopathy In A Patient With Acute Sarcoidosis

Figure 10: Clinical Approach In A patient Who PresentsWith Fever and Acute Arthritis (A), and With Fever, Arthritis, and Extra-Articular (B) Symptoms.

ReA=Reactive Arthritis; HIV=Human Immunodeficiency Virus; Gc=Gonococcal; EN=Erythema Nodosum; EM=Erythema Migrans.

Figure 11: Radiology Of The Ankle In A Patient With Septic Arthritis (Same Patient As In Fig. 1)

Figure 12: Radiology Of Left Knee In A Patient Rheumatoid Arthritis With Septic Arthritis In A Knee With Prosthesis

Figure 13: Indium-111 Labeled Leucocyte Scan In A Patient With Septic Arthritis (Same Patient As In Fig. 12)

Figure 14: Three-Phase Bone Scan With Technetium-99m Labeled Diphosphonates In A Patient With Septic Arthritis (Same Patient As In Fig. 12)

Zamani A, et al. Epidemiological and clinical features of Brucella arthritis in 24 children. Ann Saudi Med 2011;31:270-273.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR:

Ramundo MB. Fever and Rash

Hamilton JL, et al. Evaluation of fever in infants and young children. Am Fam Physician 2013;87:254-260.

Lui NL, et al. Polyarthritis in four patients with chikungunya arthritis. Singapore Med J 2012;53:241-243.

Eberst-Ledoux J, et al. Septic arthritis with negative bacteriological findings in adult native joints: a retrospective study of 74 cases. Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:156-159.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR RECENT REVIEWS

Guided Medline Search For Historical Aspects

Table of Contents

- Definitions

- Differential Diagnosis

- Clinical Approach to Diagnosis

- Laboratory Diagnosis and Imaging

- Outlines of Empiric Antibiotic Therapy in Suspected Septic Arthritis

- Other Therapeutic Options

- Prevention and Antibiotic Prophylaxis