Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections

Authors: Daniel A. Anaya, MD, E. Patchen Dellinger, MD

Necrotizing soft tissue infections are infrequent but highly lethal infections. It is estimated that there are between 500-1,500 new cases of necrotizing soft tissue infections per year in the US and a recent epidemiologic population-based study estimated the incidence of necrotizing soft tissue infections to be approximately 0.04/1,000 person-years with information derived from an insurance administrative database from various states in the United States (22). It is unclear if the incidence of this disease is increasing. However, its aggressive course, poor prognosis, and media-mediated awareness have certainly raised interest in the medical and general community. It is associated with devastating consequences including high mortality, disfigurement, disability, long-term rehabilitation and significant costs and resource utilization. Necrotizing soft tissue infections occur frequently enough that most primary care physicians, surgeons, and infectious disease specialists will see one or more during a professional career, but are infrequent enough that few will have significant experience and confidence in dealing with them (4).

DEFINITION AND NOMENCLATURE

Since the first description of necrotizing soft tissue infections by Jones, multiple terms have been used to define different kinds of necrotizing infections of the soft tissues (17, 26, 28, 39, 55). The terms used have been based on anatomic location of infection, soft tissue compartment involved, microbiologic and clinical features. Table 1 lists the different terms used to refer to necrotizing soft tissue infections. These terms have been used in an attempt to define “different” entities or to classify necrotizing soft tissue infections according to the above variables. But the reality is that the use of all these different definitions only leads to confusion and lacks any clinical or academic purpose (16, 26, 33, 36, 44).

Necrotizing soft tissue infections are defined by the presence of a spreading infection in any of the layers of the soft tissues (skin, subcutaneous tissue, superficial fascia, deep fascia, or muscles) which is associated with the presence of necrosis of the layer/s involved and hence requires surgical debridement. All necrotizing soft tissue infections fulfill this definition and have common features in their clinical presentation and diagnosis, and most importantly, all of these infections by definition require surgical debridement. It is because of this that labeling or classifying them with different terms does not serve a useful purpose and may in fact complicate management by delaying diagnosis and/or delaying surgical debridement. The true discriminative information that is essential for the management of soft tissue infections is the presence or absence of a necrotizing component and this should be the focus during the initial assessment of patients with soft tissue infections. As we will describe in the coming sections, narrowing the type of necrotizing soft tissue infections to Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus (GAS) or clostridial infection may be useful in better defining prognosis and in identifying patients that may benefit from additional treatment options. However, the general presentation, diagnosis, and management follow the same principles and we encourage the use of the unifying term necrotizing soft tissue infections when referring to all these entities.

RISK FACTORS AND ETIOLOGY

Risk Factors

Although multiple risk factors for necrotizing soft tissue infections have been described, there are no studies specifically addressing this issue. Risk factors listed in the literature include: advanced age, diabetes mellitus (including chronic diabetic foot ulcers), obesity, alcohol-use, intravenous drug use (IVDU), malnutrition, immune suppression, peripheral vascular disease, steroid use, and NSAIDs among others (16, 26, 32). These should be interpreted as conditions that have been associated with necrotizing soft tissue infections but lack data to support them as predictive of necrotizing soft tissue infections occurrence. Furthermore reports from different studies could be representing different population of patients with unequal characteristics. For example, in the study published by Wall et al, in which 31 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections were compared to 328 patients with non-necrotizing soft tissue infections, no specific conditions were found to be predictive of necrotizing soft tissue infections, except for intravenous drug use as an etiologic factor (and possibly risk factor too). However this population of patients had a very high representation of intravenous drug use (71%) as compared to other series (52). On the other hand, a more recent study also comparing patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections (n=89) with those with non-necrotizing soft tissue infections (n=225) showed that the former were more likely to have comorbidities and were more commonly associated with the presence of DM (70% vs. 51%, no p value provided) (58). Although no other studies comparing necrotizing soft tissue infections with non-necrotizing soft tissue infections have been identified, and establishing risk factors for necrotizing soft tissue infections remains difficult, multiple large series have reported what appeared to be meaningful associations between necrotizing soft tissue infections and the presence of chronic comorbidities, particularly the presence of diabetes mellitus and obesity (30-97% range) (11, 23, 24, 39, 47, 48). It remains unclear whether these are true risk factors for necrotizing soft tissue infections, but it is prudent to have a high index of suspicion in patients with chronic and debilitating comorbidities (DM, obesity, immune suppression, etc) who present with clinical or laboratory findings suggestive of necrotizing soft tissue infections.

NSAIDs have previously been described as risk factors and even causative factors for necrotizing soft tissue infections. However subsequent studies have failed to find significant relation between the use of NSAIDs and necrotizing soft tissue infections. Their use can certainly mask the initial symptoms from an ongoing soft tissue infection that can eventually progress towards necrotizing soft tissue infections, but true necrotizing soft tissue infections will probably progress regardless of the use of NSAIDs and good clinical judgment will be the key to early diagnosis and treatment (6, 14, 30).

Etiology

There are many events that can serve as etiologic factors to necrotizing soft tissue infections. Some of the published ones include: injection, trauma (lacerations, abrasions, wounds, etc.), insect bites, chronic wounds/ulcers (such as diabetic foot ulcers ![]() ), postoperative infections, perirectal abscesses, progression of minor soft tissue infections (furuncles, abscesses), etc. Two main points deserve emphasis regarding the etiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections. First, idiopathic necrotizing soft tissue infections (those occurring in previously healthy patients without an obvious source) constitute up to 20% of causes in major series, making a high level of suspicion a key factor in diagnosing the disease in patients that may not have a typical history leading to it (3, 15, 47). These patients have a higher incidence of GAS related necrotizing soft tissue infections and infections more commonly compromise the extremities. Secondly, patients that are intravenous drug use are definitely at an increased risk of developing necrotizing soft tissue infections. Intravenous drug use is the route of entry and cause of infection in 7-56% of recent series and has its own features worth mentioning

), postoperative infections, perirectal abscesses, progression of minor soft tissue infections (furuncles, abscesses), etc. Two main points deserve emphasis regarding the etiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections. First, idiopathic necrotizing soft tissue infections (those occurring in previously healthy patients without an obvious source) constitute up to 20% of causes in major series, making a high level of suspicion a key factor in diagnosing the disease in patients that may not have a typical history leading to it (3, 15, 47). These patients have a higher incidence of GAS related necrotizing soft tissue infections and infections more commonly compromise the extremities. Secondly, patients that are intravenous drug use are definitely at an increased risk of developing necrotizing soft tissue infections. Intravenous drug use is the route of entry and cause of infection in 7-56% of recent series and has its own features worth mentioning ![]() (3, 10, 15, 21).

(3, 10, 15, 21).

Bosshardt, et al published a series of patients with predominantly intravenous drug use-related necrotizing soft tissue infections over a 5-year period and showed that the incidence more than doubled when compared to the first years of the study (10). These infections seem to be particularly associated with subcutaneous and muscle injection (skin popping/muscling) of “black-tar heroin”, a cheaper, dark and gummy form of heroin that is usually mixed with diluents like dirt or coffee allowing for bacterial spores to be introduced. Most of these infections are polymicrobial but a high prevalence of anaerobic bacteria including clostridium species has been reported, which explains the high white blood cell counts associated with it as well as its rapid progression and high mortality rate, in the order of 45%. Intravenous drug use patients should be considered as a high-risk group for developing necrotizing soft tissue infections and when evaluated for soft tissue infections should undergo a thorough assessment that can confidently rule out a necrotizing infection. Admissions of multiple intravenous drug use patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections in a short interval should raise the concern for an outbreak from a “bad lot of heroin” as has previously been described in the United Kingdom and in California (18, 38, 42).

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Clinical Findings

A wide range of signs and symptoms can be seen in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. In general these can be grouped into local and systemic findings and their presence usually depends on the time of diagnosis within a continuum in the progression and extent of the infection. Most patients report a precipitating event like trauma, injection, chronic wound/boil, etc, although up to 20% can have idiopathic etiology with no identifiable cause. Initial findings include erythema, swelling ![]() , warmth and pain, often associated with tachycardia. As the infection spreads tense edema and pain out of proportion to appearance ensue and are relatively sensitive in predicting necrotizing soft tissue infections

, warmth and pain, often associated with tachycardia. As the infection spreads tense edema and pain out of proportion to appearance ensue and are relatively sensitive in predicting necrotizing soft tissue infections ![]() . At this point the skin compartment is usually spared but systemic symptoms are typically present including fever and tachycardia. When the infection progresses further, thrombosis of nutrient skin vessels occurs leading to blue discoloration that resembles ecchymoses

. At this point the skin compartment is usually spared but systemic symptoms are typically present including fever and tachycardia. When the infection progresses further, thrombosis of nutrient skin vessels occurs leading to blue discoloration that resembles ecchymoses ![]() , followed by bullae, and finally, necrosis of the skin

, followed by bullae, and finally, necrosis of the skin ![]() . At this time, nerve damage also occurs and physical exam may reveal areas of hyperesthesia combined with anesthetetic portions of the skin. Systemic signs include hypotension and associated findings consistent with severe sepsis/septic shock including mental obtundation, cardiovascular and/or pulmonary collapse among other organ system failures. Hard signs of necrotizing soft tissue infections include tense edema beyond the obvious area of inflammation, pain out of proportion to appearance, crepitus, skin blisters/bullae, skin discoloration and necrosis, usually associated with symptoms representing severe sepsis or septic shock (Table 2). If these are present, the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections is highly likely. However, most large series report the presence of 1 or more of these signs in only 10-40% of patients, and swelling, erythema and pain (typical finding for all soft tissue infections regardless of the severity) are the most common signs, present in 70-90% of the cases (3, 39, 57). The presence of subcutaneous gas diagnosed either by physical exam or by radiological studies is also an ominous sign of necrotizing soft tissue infections and can be associated with virtually any bacteria as opposed to the common perception of its unique association with clostridial infections. Most bacteria, especially facultative Gram negative rods such as Escherichia coli, make insoluble gases whenever they are forced to use anaerobic metabolism. Thus the presence of gas in a soft tissue infection implies anaerobic metabolism. Since human tissue cannot survive in an anaerobic environment, gas associated with infection implies dead tissue and therefore the presence of a surgical infection

. At this time, nerve damage also occurs and physical exam may reveal areas of hyperesthesia combined with anesthetetic portions of the skin. Systemic signs include hypotension and associated findings consistent with severe sepsis/septic shock including mental obtundation, cardiovascular and/or pulmonary collapse among other organ system failures. Hard signs of necrotizing soft tissue infections include tense edema beyond the obvious area of inflammation, pain out of proportion to appearance, crepitus, skin blisters/bullae, skin discoloration and necrosis, usually associated with symptoms representing severe sepsis or septic shock (Table 2). If these are present, the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections is highly likely. However, most large series report the presence of 1 or more of these signs in only 10-40% of patients, and swelling, erythema and pain (typical finding for all soft tissue infections regardless of the severity) are the most common signs, present in 70-90% of the cases (3, 39, 57). The presence of subcutaneous gas diagnosed either by physical exam or by radiological studies is also an ominous sign of necrotizing soft tissue infections and can be associated with virtually any bacteria as opposed to the common perception of its unique association with clostridial infections. Most bacteria, especially facultative Gram negative rods such as Escherichia coli, make insoluble gases whenever they are forced to use anaerobic metabolism. Thus the presence of gas in a soft tissue infection implies anaerobic metabolism. Since human tissue cannot survive in an anaerobic environment, gas associated with infection implies dead tissue and therefore the presence of a surgical infection ![]() .

.

Anatomic Location

Necrotizing soft tissue infections can occur in virtually any anatomic location. Most series show a predilection in the incidence of extremity infection (60-80%) followed by perineal (Fournier’s gangrene, 12-16%) and trunk infections (10-12%), but this can vary according to the specific patient population studied (3, 15). Fournier’s gangrene was first described by a French dermatologist in 1883 (Jean-Alfred Fournier) and referred as to necrotizing soft tissue infections of the male genitalia in young healthy patients ![]() . The term has been expanded to include necrotizing soft tissue infections of the perineal area in both male and female patients. It is usually secondary to skin infections, colorectal sources and urologic infections in descending order of frequency and is characteristically polymicrobial in nature. It is associated with a lower mortality when compared to other types of necrotizing soft tissue infections (16% in a recent review including 1,726 cases), although its management is associated with complications derived from complex wound care and testicular, urethral, vaginal and/or rectal involvement

. The term has been expanded to include necrotizing soft tissue infections of the perineal area in both male and female patients. It is usually secondary to skin infections, colorectal sources and urologic infections in descending order of frequency and is characteristically polymicrobial in nature. It is associated with a lower mortality when compared to other types of necrotizing soft tissue infections (16% in a recent review including 1,726 cases), although its management is associated with complications derived from complex wound care and testicular, urethral, vaginal and/or rectal involvement

![]() (19).

(19).

Progression of Infectious Process

The progression of necrotizing soft tissue infections from its precipitating cause to the florid manifestations of local and systemic derangements usually occurs over a series of days. However, occasionally patients can present with a chronic infection that slowly progresses to cause necrotizing changes over weeks with a more subacute course. It is important to assess these patients with the same approach rather than incorrectly accept the perception of non-necrotizing processes as the cause for their infection. Finally, patients with history of intravenous drug use as well as those with infections caused by mucormycosis, vibrio species, GAS and clostridial species often present with rapidly progressive and aggressive infections that require immediate surgical treatment to minimize the risk of mortality that can occur within 24 hours of onset of the infection (25, 32, 55).

DIAGNOSIS

One of the main challenges in managing patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections is the ability to diagnose the nature of the infection early in its course. Early surgical debridement is one of the main determinants of survival which in turn relies on early diagnosis and surgical referral (9, 21, 39). In essence, the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections is a clinical one and its confirmation is supported in the operating room through macroscopic and microscopic findings (49, 59). Table 3 lists the typical macroscopic and histopathologic findings seen in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. The goal in managing these patients is to be able to accomplish an early and accurate diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections before local and systemic events render the patient more susceptible to poor outcomes, primarily mortality. It is imperative to be familiar with the different tools available to be able to achieve this goal.

Biochemical Tools

Clinical diagnosis based on signs and symptoms on presentation is not reliable since early signs of necrotizing soft tissue infections are the same as those seen with non-necrotizing infections and hard signs are variable and only present in a minority of patients. Two papers have evaluated the use of laboratory findings in discriminating necrotizing from non-necrotizing infections. A study by Wall et al compared admission variables between patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections and those with non-necrotizing soft tissue infections (52). After univariate and multivariate analyses they created a model that was able to accurately predict necrotizing soft tissue infections in their population of patients. Those patients with either a white blood cell (WBC) count > 15,400 or a serum Na level < 135 mmol/L were at higher risk of having a necrotizing soft tissue infections. The model is very sensitive but not very specific with a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99% and a positive predictive value (PPV) of only 26%. Clearly it is a valuable tool when negative (rules out necrotizing soft tissue infections) but when it is positive it does not confirm the diagnosis. More recently Wong et al created a score to help discriminate between necrotizing soft tissue infections from other soft tissue infections (58). The LRINEC score (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) is based on a series of biochemical laboratory results that are readily available and can be obtained at the time of first assessment. Table 4 lists the six different variables included in the score as well as the points given for each one. The total score ranges from 0 to 13 according to the variables present. Results were categorized in three different groups: low risk (<5 points); intermediate risk (6-7 points); and high risk (≥8 points). The authors did internal validation of their score and showed that at a cutoff of ≥6 this tool had a PPV of 92% and a NPV of 96%, with scores ≥8 strongly suggestive of necrotizing soft tissue infections (PPV 93.4%). This seems like a very promising tool to help in the early diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections, however, appropriate external validation is needed. Further, a recent external-though small in sample size study failed to validate its utility at the cutoff values initially established (27). Hence, more studies are still needed and when used, it should be considered an additional tool among a battery of diagnostic tests/strategies , to help confirm or rule out the diagnosis of necrotizing soft skin infections. The advantage of using both of these models however, is that the specific laboratory parameters can be obtained at the time of admission and thereafter and the fact that they are all readily available practically in any center that manages patients with this disease.

Imaging

Imaging studies have also been used in an attempt to diagnose necrotizing soft tissue infections. Modalities used include plane X-rays, ultrasound (US), computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MRI). X-rays ![]() and CT scans

and CT scans

![]() are particularly good in showing the presence of subcutaneous gas which is considered a pathognomonic sign of necrotizing soft tissue infections. However, up to 76% of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections are reported to present without any evidence of subcutaneous gas, limiting the diagnosing potential of these two methods (34, 52). CT scans can also highlight other findings that can aid in confirming or discarding the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Deep seated abscesses or abscesses in obese patients can sometime be diagnosed only through body imaging modalities and usually are not associated with necrotizing soft tissue infections. The presence of fascial thickening with or without fat stranding has been reported to correlate well with necrotizing soft tissue infections, however this data is derived from few studies with small number of patients and hence needs further confirmation (8, 60). Ultrasound imaging has also been evaluated in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Yen et al used US diagnostic criteria for necrotizing soft tissue infections determined as the presence of diffuse thickening of the subcutaneous tissues associated with a layer of fluid accumulation >4 mm in depth along the fascial planes, when compared to unaffected contralateral areas to evaluated the role of US in diagnosing necrotizing soft tissue infections. A PPV of 83.3% and a NPV of 95.4% were seen, but again the data is based on small numbers (17 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections) and did not compare necrotizing soft tissue infections with non-necrotizing infections (61). MRI has also been suggested to help in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Positive findings reported include low intensity signal in T1 and high intensity in T2 weighed images along the fascial planes with or without gadolinium contrast uptake (T1) suggesting necrosis of the fascia. Although all these modalities add valuable information when evaluating a patient for the presence of necrotizing soft tissue infections, none are conclusive and further studies need to be done involving larger number of patients with adequate controls and well-defined and standardized criteria (7, 12, 37, 51). All of these imaging studies tend to be very sensitive but also quite non-specific. These modalities can be helpful in patients with equivocal diagnosis and in those who don’t present with overt signs of severe sepsis/shock. Ultrasound has the advantage of being portable and broadens its use to more severely ill patients, although its results are operator dependant limiting its generalizability.

are particularly good in showing the presence of subcutaneous gas which is considered a pathognomonic sign of necrotizing soft tissue infections. However, up to 76% of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections are reported to present without any evidence of subcutaneous gas, limiting the diagnosing potential of these two methods (34, 52). CT scans can also highlight other findings that can aid in confirming or discarding the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Deep seated abscesses or abscesses in obese patients can sometime be diagnosed only through body imaging modalities and usually are not associated with necrotizing soft tissue infections. The presence of fascial thickening with or without fat stranding has been reported to correlate well with necrotizing soft tissue infections, however this data is derived from few studies with small number of patients and hence needs further confirmation (8, 60). Ultrasound imaging has also been evaluated in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Yen et al used US diagnostic criteria for necrotizing soft tissue infections determined as the presence of diffuse thickening of the subcutaneous tissues associated with a layer of fluid accumulation >4 mm in depth along the fascial planes, when compared to unaffected contralateral areas to evaluated the role of US in diagnosing necrotizing soft tissue infections. A PPV of 83.3% and a NPV of 95.4% were seen, but again the data is based on small numbers (17 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections) and did not compare necrotizing soft tissue infections with non-necrotizing infections (61). MRI has also been suggested to help in the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Positive findings reported include low intensity signal in T1 and high intensity in T2 weighed images along the fascial planes with or without gadolinium contrast uptake (T1) suggesting necrosis of the fascia. Although all these modalities add valuable information when evaluating a patient for the presence of necrotizing soft tissue infections, none are conclusive and further studies need to be done involving larger number of patients with adequate controls and well-defined and standardized criteria (7, 12, 37, 51). All of these imaging studies tend to be very sensitive but also quite non-specific. These modalities can be helpful in patients with equivocal diagnosis and in those who don’t present with overt signs of severe sepsis/shock. Ultrasound has the advantage of being portable and broadens its use to more severely ill patients, although its results are operator dependant limiting its generalizability.

Transcutaneous Oxygen Saturation

Wang et al recently published an innovative strategy to help diagnose necrotizing soft tissue infections. Based on the premise that necrotizing soft tissue infections involve necrotic tissues that lack oxygen delivery they measured oxygen saturation in the affected area of 19 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections and compared it with the oxygen saturation of 215 patients with non-necrotizing cellulitis as well as with unaffected areas of the 19 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. A cutoff value of tissue oxygen saturation < 70% was associated with necrotizing soft tissue infections. This tool revealed a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 97%. The major limitation from this study is that the authors appropriately excluded patients with chronic venous stasis, peripheral vascular disease, shock and hypoxia, limiting the applicability of this tool to the minority of necrotizing soft tissue infections patients that do not have any of these coexisting conditions. It might be of use, however, in previously healthy patients who have not developed shock or hypoxia during the course of their infection, although the limited number of patients included in the study is also a significant limitation (53).

Frozen Section Biopsy and Exploration

An additional diagnostic tool in patients with suspected necrotizing soft tissue infections is frozen section of the compromised area to include fascial tissue. Stamenkovic (35, 49) and Majeski (35) have both showed a significant advantage from the use of frozen section in both diagnosing and decreasing mortality in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. The authors recommended excision of 1 cm³ from the suspected area. Histopathology findings reported to be consistent with necrotizing soft tissue infections are outlined in Table 3. Although this is a reliable method of diagnosing necrotizing soft tissue infections, delay in diagnosis typically derives from lack of suspicion rather than inappropriate work-up (34). Also, this strategy relies on the availability of pathologist as well as on their experience with this disease; it includes a significant number of negative procedures and can be associated with some degree of morbidity. Our management principles and recommendations are that if one is considering necrotizing soft tissue infections presence to be likely, the patient should be taken to the operating room for an exploration with subsequent extension of the incision and debridement if macroscopic findings confirm the disease. At the time that one is making an incision to obtain tissue for biopsy, it is usually possible to make the diagnosis based on macroscopic findings, making the incision the key step.

MICROBIOLOGY

Necrotizing soft tissue infections are typically polymicrobial in nature. Some of the largest series evaluating the microbiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections showed that 84-85% of necrotizing soft tissue infections were polymicrobial in nature (3, 20, 47). Of these, the most common microorganisms isolated vary according to patient population, however in most series the three most common isolates are anaerobic bacteria (primarily bacteroides, Gram positive cocci and clostridium), staphylococcus and streptococcus species. Other less common reported isolates include Enterobacteriaceae, fungal species and specifically mucormycosis and vibrio species, both of which usually occur in immune suppressed hosts and carry an elevated mortality in the order of 40-80% (42, 43). Table 5 lists the most common isolates from one of the largest series evaluating microbiology patterns of necrotizing soft tissue infections.

Monomicrobial infections are less common presenting in approximately 14-15% of cases from major series. The most common isolates include Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcal pyogenes (GAS), clostridial infections and more recently staphylococcus species. Series with larger representation of these isolates typically have a higher percentage of monomicrobial infections (3, 20, 47). Recent reports indicate that community acquired methicillin Staphylococcus aureus (CA-MRSA) can cause necrotizing soft tissue infections as a sole pathogen something that was extremely rare in the past (41).

Two specific infections are worth mentioning in more detail, those caused by GAS and those caused by clostridial species. They share some similarities including their unique ability to infect all the different compartments of the soft tissues including subcutaneous tissue, the fascial layers and/or the muscle compartments (myonecrosis/myositis). Although they are usually part of polymicrobial isolates, both have been reported as the most common causes of monomicrobial infections. They also cause a rapidly progressive, severe form of necrotizing soft tissue infections mediated through exotoxins in the case of clostridial infections and through cell wall components (M-protein) and exotoxins (streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxins –SPE A, B and C-) in GAS infections. Their clinical manifestations are secondary to the infectious process itself (local and systemic changes) as well as to the effect from the different toxins released at the infection site (toxic shock syndrome for clostridial infections and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome for GAS infections

![]() ) and the potential for directed therapies is valid for both types of infections (13, 32, 55).

) and the potential for directed therapies is valid for both types of infections (13, 32, 55).

In a recent study by Anaya et al, clostridial infections were associated with increased risk of mortality and limb loss when compared to other non-clostridial necrotizing soft tissue infections (38% vs. 12% for mortality and 45% vs 19.5% for limb loss, respectively). In the same study, the authors evaluated the clinical differences between these two types of infections and showed that clostridial infections are more likely to be associated with intravenous drug use, present with significantly higher admission WBC counts, are more likely to be monomicrobial in nature, and have a more severe course as seen by higher APACHE II scores and worse outcomes (3). These findings have been reproduced in other studies of clostridial necrotizing soft tissue infections) (32). Similarly, in a review of the cases of GAS-related necrotizing soft tissue infections in Ontario, Canada over a 4-year period, a similar mortality rate was seen to that of necrotizing soft tissue infections in general (34%), however when they were associated with streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (47% of the times), mortality increased significantly to 67%. Other predictors of mortality were advanced age, bacteremia, and hypotension. The use of clindamycin as well as intravenous immunoglobulin (IV Ig) was shown to be protective (31). The use of intraoperative Gram stain (predominance of Gram positive cocci) as well as the clinical course before and after debridement are tools that can help in guiding if these microorganisms can the causative factors for each specific infection, and if so consideration of directed therapies should be discussed.

TREATMENT

Necrotizing soft tissue infections like any other surgical infection is treated with a combination of source control, antimicrobial agents, and support and monitoring. However, the most essential component in managing patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections is early and complete debridement. To achieve, this early diagnosis and surgical referral is paramount and all necessary diagnostic tools to confirm the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections must be used in an efficient manner. Our practices have been that whenever in doubt, an exploration with or without subsequent debridement performed in the operating room is the safest and more expeditious way of confirming or ruling out the diagnosis and helps in establishing source control early in the course of the infection. Surgery is clearly indicated when the diagnosis of necrotizing soft tissue infections is highly likely (clinical hard signs present or diagnostic tools consistent with necrotizing soft tissue infections) as well as when patients with soft tissue infections are not responding adequately to appropriate medical treatment (not improving or worsening/spreading of the infection). An early surgical incision permits early definitive source control. If the incision does not reveal necrotizing soft tissue infections the procedure can be terminated promptly with minimal risk to the patient and a small incision that must heal.

Surgical Management

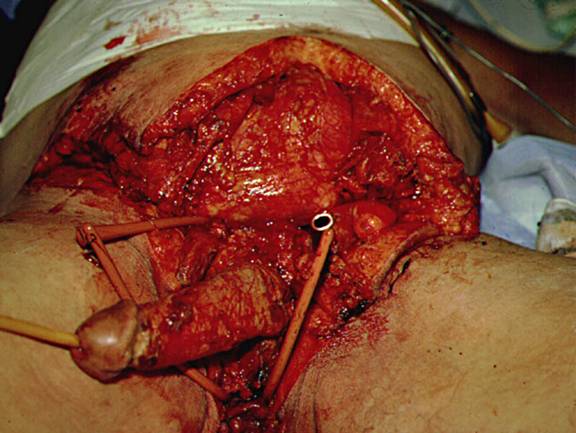

Early surgical debridement with complete removal of necrotic tissue

![]() is paramount in order to decrease mortality and other complications in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. It is probably the most important determinant of outcome in necrotizing soft tissue infections. This was well described in a study by Bilton, et al in which patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections who had adequate surgical debridement (early and complete) were compared to those with either delayed or incomplete debridements. The mortality in the latter group was 38% compared to 4.2% in the group receiving adequate surgical treatment (9). Another study, by McHenry et al analyzed 65 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections and determined that time from admission to operation was an independent predictor of mortality. This was 90 hours in non-survivors versus 25 hours in survivors (p=0.0002) (39). Other studies have corroborated these findings too (21, 34, 35, 49).

is paramount in order to decrease mortality and other complications in patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. It is probably the most important determinant of outcome in necrotizing soft tissue infections. This was well described in a study by Bilton, et al in which patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections who had adequate surgical debridement (early and complete) were compared to those with either delayed or incomplete debridements. The mortality in the latter group was 38% compared to 4.2% in the group receiving adequate surgical treatment (9). Another study, by McHenry et al analyzed 65 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections and determined that time from admission to operation was an independent predictor of mortality. This was 90 hours in non-survivors versus 25 hours in survivors (p=0.0002) (39). Other studies have corroborated these findings too (21, 34, 35, 49).

Once the decision to take the patient for an operation has been made, the initial incision is done in the compromised area and the wound is explored for macroscopic findings of necrotizing soft tissue infections including the blunt dissection and the “finger test”. The extent of the infection is generally greater than the preoperative external evidence

![]() . Removal of all non-viable tissue should be accomplished including skin if it is compromised and one should extend the incision until healthy viable tissue is seen. Removal of previously viable skin should usually not be done at the initial operation. Its perfusion and viability can easily be assessed at re-exploration, and removal at that time is easy if indicated. Clues to help determine the extent of the infection are listed in Table 3. Amputation of a limb is rarely required at the time of initial debridement. However if it compromises the muscle component and complete source control requires amputation, one should proceed with this plan, usually after agreement with another surgeon (37). In their analysis of 166 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections, Anaya et al found independent predictors of limb loss to be: clostridial infection, shock at admission and pre-existing heart disease. This study had a significant number of patients with intravenous drug use who were also found to have a higher risk of limb loss (probably related to clostridial infections and myonecrosis). This information as well as tools that aid in determining the risk of mortality can be used to weigh the potential benefits of early amputation in patients with a high mortality risk.

. Removal of all non-viable tissue should be accomplished including skin if it is compromised and one should extend the incision until healthy viable tissue is seen. Removal of previously viable skin should usually not be done at the initial operation. Its perfusion and viability can easily be assessed at re-exploration, and removal at that time is easy if indicated. Clues to help determine the extent of the infection are listed in Table 3. Amputation of a limb is rarely required at the time of initial debridement. However if it compromises the muscle component and complete source control requires amputation, one should proceed with this plan, usually after agreement with another surgeon (37). In their analysis of 166 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections, Anaya et al found independent predictors of limb loss to be: clostridial infection, shock at admission and pre-existing heart disease. This study had a significant number of patients with intravenous drug use who were also found to have a higher risk of limb loss (probably related to clostridial infections and myonecrosis). This information as well as tools that aid in determining the risk of mortality can be used to weigh the potential benefits of early amputation in patients with a high mortality risk.

Scheduled re-explorations should be done at least every 6-48 hours after the initial operation or sooner if clinical local or systemic signs of worsening infection become evident, as well as with worsening laboratory parameters (particularly WBC count). Re-explorations should be repeated until the time when very little or no debridement is required.

ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY

The use of antimicrobial therapy is only an adjuvant treatment and must be combined with early surgical debridement. Once the diagnosis is made and blood cultures have been drawn, broad spectrum coverage with activity against Gram positive, Gram negative, and anaerobic organisms should be started. This can be done with single-agent regimens or multiple agents. Single agent regimens include piperacillin/tazobactam, imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem (Invanz®) and tigecycline. Multiple agent regimens include a fluoroquinolone or an aminoglycoside combined with either clindamycin or metronidazole, sometimes combined with high dose penicillin G (up to 24 million units per day). Clindamycin is a protein-synthesis inhibitor and may help by decreasing toxin production in clostridial and Group A beta-hemolytic Streptococcal pyogenes infections. Some animal and human studies have shown improved outcomes with the use of this antimicrobial (50, 62). Vancomycin should be added if MRSA is endemic in the area and considered a likely isolate (54).

Support and Monitoring

An additional adjunct to surgical debridement and antimicrobial therapy is physiologic support. This includes adequate fluid resuscitation ideally before the patient is anesthetized if possible as well as in the postoperative period. Oxygen supplementation is usually needed. In advanced stages of the disease, organ failure ensues requiring pressor support, mechanical ventilation and/or renal replacement therapies. Pre- and post- operatively it is not uncommon to see some degree of coagulopathy from sepsis as well as from intraoperative bleeding and dilution effect from aggressive crystalloid, colloid and red blood cells resuscitation. Early nutritional support combined with tight glucose control is key to countering the catabolic response of these patients and decreasing future infectious complications as well as for promoting anabolism and wound healing once they have recovered from the infectious process.

Close monitoring in an intensive care unit is our preferred method for the perioperative period. This includes constant monitoring and correction of physiologic effects of necrotizing soft tissue infections as well as frequent laboratory measurements. We have seen that WBC monitoring up to every 6 hours after the initial debridement has helped in identifying patients that may benefit from earlier re-operations.

Other Adjunctive Therapies

Despite significant advancements in critical care management as well as improved knowledge regarding necrotizing soft tissue infections, mortality remains relatively high. Adjunctive and more unconventional treatment options have been explored in an effort to improve outcomes in this group of patients.

Hyperbaric oxygen is one of these modalities. It is a medical treatment that uses delivery of 100% oxygen at a pressure of 2-3 atmospheres absolute. Its use is motivated by the fact that oxygen delivery at these parameters achieves a much higher concentration of dissolved oxygen in blood which results in higher tissue oxygen tensions. At this higher tissue tension, beneficial effects may be seen including improved leukocyte function, inhibition of anaerobic growth, inhibition of toxin production and enhancement of antibiotic activity. Riseman, et al published a study in which they retrospectively compared patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections receiving hyperbaric oxygen versus those who did not (46). Clinical and microbiologic variables and treatment strategies were otherwise similar for both groups and in fact patients receiving hyperbaric oxygen were more severely compromised. Mortality in hyperbaric oxygen-treated patients was 23% compared to 66% for those who did not receive hyperbaric oxygen. The number of wound debridements (and hence tissue loss) was also smaller for hyperbaric oxygen-treated patients. Unfortunately these results have not been reproduced in other studies evaluating hyperbaric oxygen in necrotizing soft tissue infections. Furthermore, the use of hyperbaric oxygen will many times involve transporting the patient to outside facilities were the hyperbaric oxygen chambers are available and this not only complicates the management of these patients (particularly since recommended regimens include at least 3 90 minute sessions/day for a few days) but may compromise more standard and vital therapies including repeated surgical debridements (28). Benefit remains controversial. If it is to be used it should not interfere with delivery of primary therapy (particularly surgical debridements). Future trials may better be able to define selected population of patients that can benefit from this therapy (i.e. clostridial and other toxin-producing infections).

Similarly, intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) has been postulated to improve outcomes in a selected population of patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. Most of the studies reported evaluate its use for invasive GAS infections including GAS-related necrotizing soft tissue infections and streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Kaul, et al reported their experience with GAS-related necrotizing soft tissue infections and identified IVIg as well as clindamycin to be protective factors against mortality in patients that had progressed to streptococcal toxic shock syndrome. Although there are a wide number of studies reporting observations from the use of IVIg in GAS infections, there are no conclusive papers evaluating its effect on GAS-related necrotizing soft tissue infections. The volume of IVIg given is so large that one must wonder if much of the observed benefit is derived from the resulting aggressive volume infusion. From Kaul’s experience, one can state that the use of IVIg is reasonable in patients with documented GAS-related necrotizing soft tissue infections, particularly those that have a higher risk of mortality (advanced age, hypotension and bacteremia) and also its use can be recommended in patients who have progressed to streptococcal toxic shock syndrome (31, 45).

PROGNOSIS

A recent review of published reports calculated the pooled mortality of necrotizing soft tissue infections to be 34% (39). A series of predictors of mortality have been identified from the most recent and larger series. These include age, female gender, medical comorbidities, diabetes mellitus, peripheral vascular disease, admission blood pressure, admission temperature, acidosis, admission creatinine, lactate level, clostridium and GAS infections, 10, 15,21, 23, 34, 35, 39, 44, 48, 57). However not all of these predictors apply to all groups of patients and even results from the largest series are not consistent throughout. With that in mind Anaya et al evaluated all possible variables that could have an impact on mortality and limb loss on a group of 166 patients with necrotizing soft tissue infections. After univariate and multivariate analysis independent predictors of mortality included: admission WBC count > 30,000; admission creatinine >2.0 mg/dl, clostridial infection and heart disease. Since clostridial infections can not be predicted at the time of admission, they compared patients with and without clostridial sources and identified high WBC count as a surrogate marker for clostridial infection. In fact, an admission WBC count of 30,000 was associated with a mortality of between 15-20% and when WBC counts reached the 40,000 mark mortality escalated to reach >50% (3). More recently, this group has created a clinical score based on 350 necrotizing soft tissue infections patients from two tertiary referral institutions that predicts mortality within three different risk-categories (Table 6) (5). With external validation of this score, it could become a tool to help in establishing which patients might benefit from more aggressive surgical intervention (early amputation) and novel therapeutic approaches, and in the selection of patients for future trials.

SUMMARY

Necrotizing soft tissue infections constitutes a group of infections affecting any component of the different soft tissue compartments associated with necrosis of the involved layers. These infections should be grouped and referred to as necrotizing soft tissue infections, and other labels and classifications should be de-emphasized. No validated risk factors have been identified although patients with history of intravenous drug use as well as those with chronic debilitating comorbidities (DM, immune suppression) appear to have an increased risk. Multiple etiologic or precipitating events have been identified but up to 20% are idiopathic in nature. Diagnosis is challenging but there are enough tools including clinical findings, biochemical parameters, scores, imaging aids and invasive procedures that can help make the diagnosis. When in doubt, exploration of the compromised tissue should be performed. The mainstay of treatment is early and adequate surgical debridement with scheduled returns to the operating room. Adjuncts to debridement include broad-spectrum antibiotics as well as strict physiologic support and monitoring. Hyperbaric oxygen and intravenous immunoglobulin are more unconventional treatment options that can be considered in selected groups of patients. Mortality remains high and future trials should be focused on the ability to make an early diagnosis. Current and future predictive models can be used to apply different treatment strategies in high-risk patients, where the risk-benefit may be more substantial.

REFERENCES

1. (2000). "Unexplained illness and death among injecting-drug users--Glasgow, Scotland; Dublin, Ireland; and England, April-June 2000." MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2000;49: 489-92. [PubMed]

2. (2003). "Wound botulism among black tar heroin users--Washington." MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2003;52: 885-6. [PubMed]

3. Anaya DA, McMahon K, et al. "Predictors of mortality and limb loss in necrotizing soft tissue infections." Arch Surg 2005;140(2): 151-7; discussion 158.[PubMed]

4. Anaya DA, Dellinger EP. Necrotizing soft-tissue infection: diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis 2007:44 (5);705-710.[PubMed]

5. Anaya DA, Bulger EM, Kwon YS, Kao LS, Evans H, Nathens AB. Predicting death in necrotizing soft tissue infections: a clinical score. Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009;10 (6):517-22.

6.Aronoff DM, and Bloch KC. "Assessing the relationship between the use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs and necrotizing fasciitis caused by group A streptococcus." Medicine 2003;82: 225-35. [PubMed]

7.Arslan A, Pierre-Jerome C, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis: unreliable MRI findings in the preoperative diagnosis." Eur J Radiol 2000;36:139-43. [PubMed]

8. Becker M, Zbaren P, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis of the head and neck: role of CT in diagnosis and management." Radiology 1997;202: 471-6. [PubMed]

9. Bilton BD, Zibari GB, et al. "Aggressive surgical management of necrotizing fasciitis serves to decrease mortality: a retrospective study." Am Surg 1998;64:397-400; discussion 400-1. [PubMed]

10. Bosshardt TL, Henderson VJ, et al. "Necrotizing soft-tissue infections." Arch Surg 1996;131: 846-52; discussion 852-4. [PubMed]

11. Brandt MM, Corpron CA, et al. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: a surgical disease." Am Surg 2000;66:967-70; discussion 970-1. [PubMed]

12. Brothers TE, Tagge DU, et al. "Magnetic resonance imaging differentiates between necrotizing and non-necrotizing fasciitis of the lower extremity." J Am Coll Surg 1998;187: 416-21. [PubMed]

13. Brown EJ. "The molecular basis of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome." N Engl J Med 2004;350: 2093-4. [PubMed]

14. Browne BA, Holder EP, et al. "Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and necrotizing fasciitis." Am J Health Syst Pharm 1996;53: 265-9. [PubMed]

15. Childers BJ, Potyondy LD, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis: a fourteen-year retrospective study of 163 consecutive patients." Am Surg 2002;68:109-16. [PubMed]

16.Cunningham JD, Silver L, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis: a plea for early diagnosis and treatment." Mt Sinai J Med 2001;68: 253-61. [PubMed]

17. Descamps V, Aitken J, et al. "Hippocrates on necrotising fasciitis." Lancet 1994;344: 556.[PubMed]

18. Ebright JR, Pieper B. "Skin and soft tissue infections in injection drug users." Infect Dis Clin North Am 2002;16: 697-712. [PubMed]

19. Eke N. "Fournier's gangrene: a review of 1726 cases." Br J Surg 2000;87: 718-28. [PubMed]

20. Elliott D, Kufera JA, et al. "The microbiology of necrotizing soft tissue infections." Am J Surg 2000;179: 361-6.[PubMed]

21. Elliott DC, Kufera JA, et al. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections. Risk factors for mortality and strategies for management." Ann Surg 1996;224: 672-83.

22. Ellis Simonsen SM, van Orman ER, et al. "Cellulitis incidence in a defined population." Epidemiol Infect 2006;134: 293-9. [PubMed]

23. Faucher LD, Morris SE, et al. "Burn center management of necrotizing soft-tissue surgical infections in unburned patients." Am J Surg 2001;182: 563-9. [PubMed]

24. Gallup DG, Freedom MA. "Necrotizing fasciitis in gynecologic and obstetric patients: a surgical emergency." Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000;187: 305-10; discussion 310-1. [PubMed]

25. Goodell KH, Jordan MR, et al. "Rapidly advancing necrotizing fasciitis caused by Photobacterium (Vibrio) damsela: a hyperaggressive variant." Crit Care Med 2004;32: 278-81. [PubMed]

26. Green RJ, Dafoe DC, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis." Chest 1996;110: 219-29. [PubMed]

27. Holland MJ. Application of the Laboratory Risk Indicator in Ncrotizing Fascitis (LRINEC) score to patinets in a tropical tertiary referral centre. Anaesth Intensive Care 2009;37 (4):588-92. [PubMed]

28. Jallali N, Withey S, et al. "Hyperbaric oxygen as adjuvant therapy in the management of necrotizing fasciitis." Am J Surg 2005;189: 462-6. [PubMed]

29. Jones J. "Surgical memoirs of the war of the rebellion. Investigation upon the nature, causes and treatment of hospital gangrene as prevailed in the Confederate armies 1861-1865." New York: US Sanitary Commission, 1871.

30. Kahn L, Styrt BA. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections reported with nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs." Ann Pharmacother 1997;31: 1034-9. [PubMed]

31. Kaul R, McGeer A, et al. "Population-based surveillance for group A streptococcal necrotizing fasciitis: Clinical features, prognostic indicators, and microbiologic analysis of seventy-seven cases. Ontario Group A Streptococcal Study." Am J Med 1997;103: 18-24. [PubMed]

32. Kimura AC, Higa JI, et al. "Outbreak of necrotizing fasciitis due to Clostridium sordellii among black-tar heroin users." Clin Infect Dis 2004;38: e87-91. [PubMed]

33. Kuncir EJ, Tillou A, et al.. "Necrotizing soft-tissue infections." Emerg Med Clin North Am 2003;21:1075-87. [PubMed]

Lille ST, Sato TT, et al. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: obstacles in diagnosis." J Am Coll Surg 1996;182:7-11.[PubMed]

34. Lille ST, Sato TT, et al. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: obstacles in diagnosis." J Am Coll Surg 1996;182:7-11. [PubMed]

35. Majeski J, Majeski E. "Necrotizing fasciitis: improved survival with early recognition by tissue biopsy and aggressive surgical treatment." South Med J 1997;90:1065-8. [PubMed]

36. Majeski JA, John JF, Jr. "Necrotizing soft tissue infections: a guide to early diagnosis and initial therapy." South Med J 2003;96:900-5. [PubMed]

37. Marshall JC, Maier RV, et al. "Source control in the management of severe sepsis and septic shock: an evidence-based review." Crit Care Med 2004;32(11 Suppl): S513-26. [PubMed]

38. McGuigan CC, Penrice GM, et al. "Lethal outbreak of infection with Clostridium novyi type A and other spore-forming organisms in Scottish injecting drug users." J Med Microbiol 2002;51: 971-7. [PubMed]

39. McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, et al. "Determinants of mortality for necrotizing soft-tissue infections." Ann Surg 1995;221: 558-63; discussion 563-5. [PubMed]

40. Meleney F. "Hemolytic Streptococcus Gangrene." Arch Surg 1924;9: 317-64.

41. Miller LG, Perdreau-Remington F, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis caused by community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Los Angeles." N Engl J Med 2005;352: 1445-53. [PubMed]

42. Oliver JD. "Wound infections caused by Vibrio vulnificus and other marine bacteria." Epidemiol Infect 2005;133: 383-91. [PubMed]

43. Patino JF, Castro D, et al. Necrotizing soft tissues: a review. World J Surg 1991;15:235-9.

44. Patino JF, Castro D, et al. "Necrotizing soft tissue lesions after a volcanic cataclysm." World J Surg 1991;15:240-7.[PubMed]

45. Perez CM, Kubak BM, et al. "Adjunctive treatment of streptococcal toxic shock syndrome using intravenous immunoglobulin: case report and review." Am J Med 1997;102: 111-3. [PubMed]

46. Riseman JA, Zamboni WA, et al. "Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for necrotizing fasciitis reduces mortality and the need for debridements." Surgery 1990;108: 847-50. [PubMed]

47. Singh G, Ray P, et al. "Bacteriology of necrotizing infections of soft tissues." Aust N Z J Surg 1996;66:747-50. [PubMed]

48. Singh G, Sinha SK, et al. "Necrotising infections of soft tissues--a clinical profile." Eur J Surg 2002;168: 366-71. [PubMed]

49. Stamenkovic I, Lew PD. "Early recognition of potentially fatal necrotizing fasciitis. The use of frozen-section biopsy." N Engl J Med 1984;310:1689-93. [PubMed]

50. Stevens DL, Gibbons AE, et al. "The Eagle effect revisited: efficacy of clindamycin, erythromycin, and penicillin in the treatment of streptococcal myositis." J Infect Dis 1988;158: 23-8. [PubMed]

51. Struk DW, Munk PL, et al. "Imaging of soft tissue infections." Radiol Clin North Am 2001;39: 277-303. [PubMed]

52. Wall DB, Klein SR, et al. "A simple model to help distinguish necrotizing fasciitis from nonnecrotizing soft tissue infection." J Am Coll Surg 2000;191: 227-31. [PubMed]

53. Wang TL, Hung CR. "Role of tissue oxygen saturation monitoring in diagnosing necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs." Ann Emerg Med 2004;44: 222-8. [PubMed]

54. Weigelt J, Itam K, Stevens D, Lau W, Dryden M, Knirsch C, and the Linezolid CSSTI Study Group. Linezolid versus vancomycin in the Treatment of Complicated Skin and Soft Tissue Infections. Antimicrobe Agents Chemother 2005;49:2260-2266.

55. Weiss KA, Laverdiere M. "Group A Streptococcus invasive infections: a review." Can J Surg 1997;40: 18-25. [PubMed]

56. Wilson B. "Necrotizing fasciitis." Am Surg 1952;18: 416-31. [PubMed]

57. Wong CH, Chang HC, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis: clinical presentation, microbiology, and determinants of mortality." J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003;85-A(8):1454-60. [PubMed]

58. Wong CH, Khin LW, et al. "The LRINEC (Laboratory Risk Indicator for Necrotizing Fasciitis) score: a tool for distinguishing necrotizing fasciitis from other soft tissue infections." Crit Care Med 2004;32: 1535-41. [PubMed]

59. Wong CH, Wang YS. "The diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis." Curr Opin Infect Dis 2005;18: 101-6. [PubMed]

60. Wysoki MG, Santora TA, et al. "Necrotizing fasciitis: CT characteristics." Radiology 1997;203: 859-63. [PubMed]

61. Yen ZS, Wang HP, et al. "Ultrasonographic screening of clinically-suspected necrotizing fasciitis." Acad Emerg Med 2002;9:1448-51. [PubMed]

62. Zimbelman J, Palmer A, et al. "Improved outcome of clindamycin compared with beta-lactam antibiotic treatment for invasive Streptococcus pyogenes infection." Pediatr Infect Dis J 1999;18: 1096-100. [PubMed]

Tables

Table 1. Common Terms Used to Refer to Specific Types of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections.

| Different nomenclature |

|---|

|

[Daniel Anaya and E. Patchen Dellinger, MD: History of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections Terminology]

Table 2. Clinical Hard Signs of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections

| Hard signs of NSTI |

|---|

+/-

|

Table 3. Macroscopic and Histopathologic Findings of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections

| Macroscopic findings of NSTI |

|---|

|

| Histopathologic findings of NSTI |

|

*"Finger test" refers to blunt dissection of the tissues with the index finger. It’s considered positive when there is lack of resistance to finger dissection of normally adherent tissues.

Table 4. Variables Included in the LRINEC Score for Diagnosing NSTI

| Variable (units) | Score points |

|---|---|

| C-Reactive Protein (CRP) (mg/L) | |

< 150 |

0 |

| >150 | 4 |

| White blood cell count (per mm³) | |

| <15 | 0 |

| 15-25 | 1 |

| >25 | 2 |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | |

| >13.5 | 0 |

| 11-13.5 | 1 |

| <11 | 2 |

| Sodium (mmol/L) | |

| ≥135 | 0 |

| <135 | 2 |

| Creatinine | |

| ≤141 μmol/L (1.6 mg/dl) | 0 |

| >141 μmol/L (1.6 mg/dl) | 2 |

| Glucose | |

| ≤10 mmol/L (180 mg/dl) | 0 |

| >10 mmol/L (180 mg/dl) | 1 |

Internal validation revealed that at a cutoff of ≥6 had a PPV of 92% and a NPV of 96%.

Scores ≥8 strongly suggestive of NSTI (PPV 93.4%).Table 5. Isolated Microorganisms and Type of Infections from Patients with Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections in a Series of 182 Patients.

| MICROORGANISM | No. of isolates (n=791 isolates) |

|---|---|

Anaerobes Bacteroides/Prevotella spp Peptostreptococcus Clostridium |

263 136 49 37 |

Streptococcus species (including enterococcus) Groups A β-hemolytic |

236 57 |

Staphylococcus species |

77 |

Other (including other Gram positives, Gram negatives and fungi) |

215 |

| TYPE OF INFECTION | Number of patients (n=182) |

Polymicrobial infection |

154 (85%) |

Monomicrobial infection

|

28 (15%)

|

Table 6. Prognostic Score to Predict Mortality in Patients with Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection, At Time of First Assessment.

| VARIABLE (on admission) | Number of points | |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate > 110 | 1 | |

| Temperature < 36°C | 1 | |

| Creatinine > 1.5 mg/dl | 1 | |

| Age > 50 | 3 | |

| White blood cell count > 40,000 |

3 | |

| Hematocrit > 50 | 3 | |

| GROUP CATEGORIES | Number of points | Mortality risk |

| 1 | 0-2 | 6% |

| 2 | 3-5 | 24% |

| 3 | ≥ 6 | 88 |

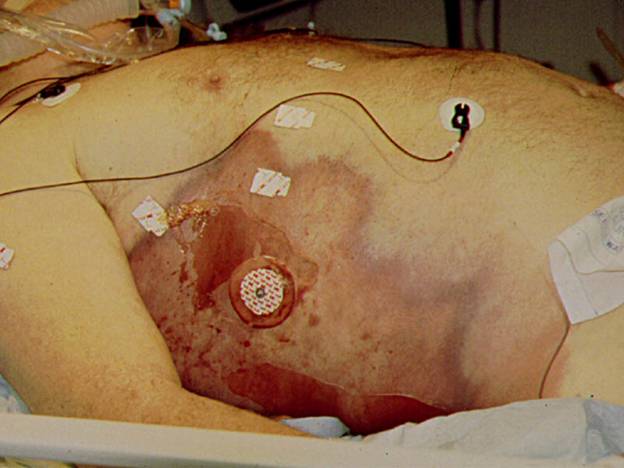

Figure 1. Intravenous Drug Use-Related Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection

Figure 2. Tense Edema Beyond Area of Inflammation in a Patient with Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection in the Lower Extremity.

Figure 3. Skin Discoloration/Ecchymosis in a Patient with Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection of the Trunk.

Figure 4. Subcutaneous Gas in a Plane X-ray of a Patient with Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection of the Lower Extremity.

Figure 5. Scrotal Changes (Tense Edema, Ecchymosis) in a Patient with Fournier’s Gangrene.

Figure 6. Resulting Wound from Aggressive Debridement in a Patient with Fournier’s Gangrene.

Figure 7: Appearance of Infected Subcutaneous Tissue Extending Far Beyond External Evidence of Infection and Found Under Normal Appearing Skin and Adjacent to Normal Appearing Subcutaneous Tissue. This Photo Taken at the Initial Operation for Debridement of the Patient Illustrated in Figure 5.

Tilkorn DJ, et al. Characteristics and differences in necrotizing fasciitis and gas forming myonecrosis: a series of 36 patients. Scand J Surg 2012;101:51-55.

Willy C, et al. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy for necrotizing soft tissue infections: contra. Chirurg 2012;83:960-972.

McGillicuddy EA, et al. Development of a Computed Tomography-Based Scoring System for Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. J Trauma 2011;70;894-899.

Guided Medline Search For:

Goh T, et al. Early diagnosis of necrotizing fasciitis. Br J Surg 2014;101:e119-e125.

Guided Medline Search For Recent Reviews

History

Daniel Anaya and E. Patchen Dellinger, MD: History of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections Terminology