Transplant Infection: Histoplasmosis

Authors: C.A. Hage, M.D., L. Pescovitz, M.D., J. Wheat, M.D.

INTRODUCTION

The first case of progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in a transplant patient was reported in 1964; the patient died two weeks following renal transplantation (11). Although post-transplantation is the underlying condition in 7% (1) to 11% (31) of patients with progressive disseminated histoplasmosis, it occurs in less than 0.5% of transplant recipients in endemic areas. Once suspected, the diagnosis can usually be established within a few days. Treatment, if initiated before the illness becomes severe, is highly effective, and should be given for at least one year. Immunosuppression should be reduced during treatment. Life-long antifungal suppressive therapy may be unnecessary in patients with good allograft function while receiving low dose immunosuppression.

MYCOLOGY

Tuberculated macroconidia are characteristic of the mould and are used for identification of the organisms in cultures. The mould grows in soil containing decayed bird or bat guano. Laboratory identification requires conversion of the mould to the yeast, identification of specific antigens by immunologic tests, or genetic verification using nucleic acid probes. H. capsulatum grows at temperatures above 35°C as yeasts, which are the pathogenic forms found in the tissues of infected individuals.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

H. capsulatum is endemic to certain parts of North and South America, Africa, and Asia. Most cases in transplant patients occur in endemic areas following exogenous infection. Histoplasmosis also may occur in transplant patients who have visited endemic areas, and rarely following transplantation of organs from cadaveric donors with unrecognized active histoplasmosis (20). However, even in endemic areas, the incidence is low (<0.5%), except during outbreaks in the general population, when rates of about 2% have been reported (41).

PATHOGENESIS

Histoplasmosis is acquired by inhaling microconidia or hyphal fragments of the mould phase of the organism. T cell immunity provides the primary host defense against H. capsulatum, explaining why the infection is usually progressive in organ-transplant recipients who are receiving or have received potent T cell suppressors. While some postulate that reactivation of latent infection occurs in transplant patients (8), reactivation appears to be uncommon. For example, not one of over 500 patients undergoing solid organ or bone marrow transplantation in Indianapolis developed histoplasmosis (36). As further evidence against reactivation, H. capsulatum could not be grown from calcified pulmonary granulomas in which yeasts were seen and the granulomas failed to cause histoplasmosis when injected into mice (33). Acquisition also may occur by transplantation of organs from donors with histoplasmosis. Illness usually occurs within the first month of transplantation if the donor died of disseminated histoplasmosis (2) and six to 12 months following transplantation if small numbers of viable yeast in the transplanted organ proliferated during immunosuppression (20).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

Healthy subjects develop protective cellular immunity to H. capsulatum during the first month following infection, and recover without long-term sequelae. Transplant patients receiving immunosuppressive medications have reduced ability to mount an effective cellular immune response and therefore may exhibit a progressive infection characterized by extra-pulmonary dissemination (6,8,15,41). Respiratory manifestations are present in most patients, and radiograph usually show miliary or diffuse reticulonodular infiltrates. Other common findings include fever, weight loss, hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, cutaneous or subcutaneous lesions, and mucosal lesions in the mouth or gastrointestinal tract. Central nervous system involvement occurs in about 5-10% of cases.

Unusual manifestations have included necrotizing soft tissue infection (3,21,24,37), pericarditis (27), bone or joint lesions (32), thrombotic microangiopathy (12), and hemophagocytic syndrome (23). Laboratory abnormalities may show evidence for bone marrow suppression and hepatic inflammation. Patients with severe infection may exhibit shock, respiratory failure, and consumptive coagulopathy, and other features suggestive of severe bacterial infection.

Paradoxical worsening of symptoms despite evidence for response to antifungal treatment is consistent with immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS). Possible IRIS has been noted in patients with histoplasmosis after stopping TNF blockers for inflammatory disorders (Hage CID 2010, in press) or other immunosuppressive agents and in patients with AIDS who have initiated anti-retroviral treatment (9). Findings of IRIS may be misinterpreted as a sign of treatment failure (26). IRIS should be suspected if clinical worsening is occurring in conjunction with decreasing antigen concentrations.

DIAGNOSIS

Since histoplasmosis is an uncommon infection in solid organ transplant patients, diagnostic workup should include testing for the more common infections such as CMV. This review, however, focuses on the approach to diagnosis of histoplasmosis. Rapid diagnosis of histoplasmosis can usually be established by detection of antigen in the urine and/or serum. Serologic tests are insensitive but may provide a clue to diagnosis in some cases. The diagnosis can be confirmed by isolation of the organism from tissues or body fluids in most cases, although several weeks may be required to identify positive cultures.

Antigen Detection

Although the sensitivity was 100% in cases evaluated at the Indiana University –Clarian Health campus (Table 1) and at the University of Nebraska (15), false negative results may occur (6). Serum and urine should be tested in all cases to achieve the highest sensitivity. Cross reactions can occur in patients with other endemic mycoses, most notably blastomycosis (5) but also coccidioidomycosis (5), which are less common than histoplasmosis.

Histoplasmosis may cause a positive result for galactomannan in the Platelia™ Aspergillus EIA (42) or beta glucan in the Fungitell® beta glucan assay (13), leading to a mistaken diagnosis of aspergillosis, candidiasis, or Pneumocystis jiroveci infection (28). Histoplasma antigen should be determined in serum and urine in patients with positive results for Aspergillus galactomannan or beta-glucan if the patient or donor had exposure to an endemic area.

Pathology

Fungal stain of BAL or tissue may provide a rapid diagnosis, and is positive in over three-quarters of cases (6) (Table 1). However, the availability of an assay for detection of antigen in body fluids has reduced the need for invasive procedures to obtain specimens for fungal stain. For example, diagnosis was based on fungal stain in only 11% of patients at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (15), and half at Indiana University (Table 1).

Culture

Cultures were positive in about half of cases at Indiana University (Table 1). BAL cultures were positive in one third (Table 1) to one half (6,15) of cases. Blood cultures were performed in all cases in two studies and were positive in 43% in one (6) and 67% in the other (15). Histoplasma was isolated from bone marrow in 43% of patients in one study, including two with negative blood cultures (6).

While culture may not provide a rapid diagnosis, requiring up to one month for growth, it may be the only laboratory basis for diagnosis in some cases, and the basis for diagnosis of co-infection in others. Culture of blood using methods appropriate for isolation of fungi should be performed in all patients. Cutaneous, oral, or gastrointestinal lesions may also be sources for isolation of the fungus.

Serology

Serology was positive in 33% of patients in the Cuellar-Rodriguez study (6) and 20 % in this review(41), compared to 100% in an earlier review of cases at the Indiana Univeristy. These findings suggest that recent changes in immunosuppressive regimens may have impaired antibody production, reducing the value of serologic testing. Antibodies may persist for several years following recovery from histoplasmosis, and may not indicate active disease. Furthermore, cross reactions are possible in patients with other endemic mycoses. While not as useful as pathology or antigen detection, serology but may provide a clue in some cases.

Molecular Diagnostics

The published studies have not demonstrated superiority of PCR over other rapid methods. PCR was falsely-negative in 31% of tissues in which yeast resembling H. capsulatum were seen by histopathology (4). Tang evaluated PCR on urine specimens from patients with histoplasmosis, noting positive results in only 8% of specimens with elevated Histoplasma antigen results, restricted to specimens from which Histoplasma was isolated (34): in unpublished experiments PCR was negative in other body fluids (BAL, CSF, serum) from patients with histoplasmosis (Wheat, 2006). Qualtieri reported detection of Histoplasma DNA in the blood from a renal transplant patient with histoplasmosis, in whom blood cultures were negative but in whom high levels of urinary antigen were detected (29). However, until the accuracy of PCR relative to that of other rapid methods is established, and standardized and validated methods are available, the role of this approach to diagnosis remains uncertain (10).

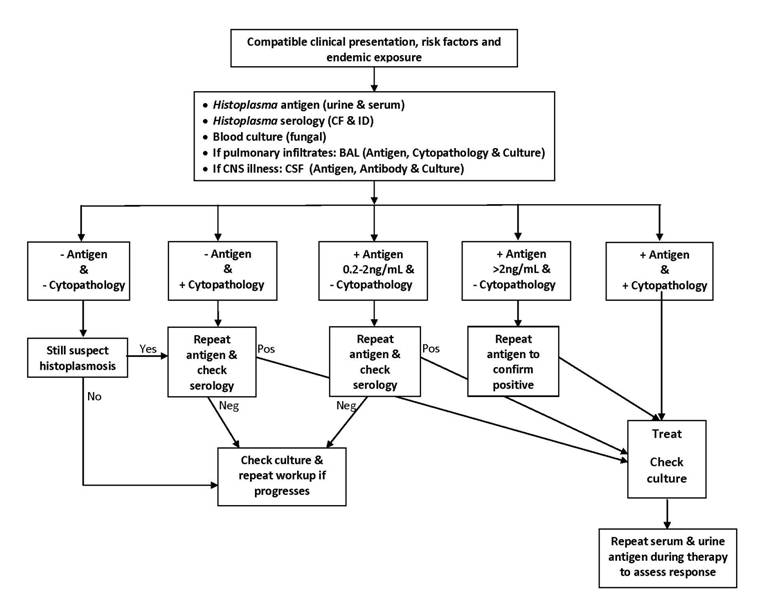

Diagnostic Algorithm

While a broader diagnostic approach is needed to diagnose the more common infections following organ transplantation, evaluation for histoplasmosis should include antigen testing of serum and urine and fungal blood cultures in all patients. Pulmonary involvement is present in most cases. If bronchoscopy is performed, testing should include evaluation of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) for fungal organisms by cytopathology and Histoplasma antigen detection. BAL is advised if pulmonary infiltrates are present and pulmonary function is adequate to undergo bronchoscopy. If central nervous system symptoms are present cerebrospinal fluid should be collected and tested for antigen, antibody and fungal culture. A diagnostic algorithm for histoplasmosis is presented in (Figure 1).

Biopsy of bone marrow, liver, or other lesions may be required to establish the diagnosis by fungal stain and culture if the above tests are non-diagnostic. Serological tests may provide a clue in some patients. Both complement fixation and immunodiffusion are recommended to improve the yield of serology.

TREATMENT

Liposomal amphotericin B 3 mg/kg/day is recommended for patients with moderately severe or severe manifestations, and 5 mg/kg/day for Histoplasma meningitis (40). Studies in patients with AIDS showed that the liposomal formulation was more effective and less nephrotoxic than deoxycholate amphotericin B (17). If other lipid formulations are used, 5 mg/mg/day is recommended. In recent series of histoplasmosis cases following transplantation, 94% of patients treated with amphotericin B had favorable responses (6,15): only one of 17 (6%) patients died (15) and another relapsed when treatment was stopped but responded to a second course of treatment (6). Amphotericin B can be replaced by itraconazole after a one to two week induction phase, except in patients with central nervous system involvement, in whom 5-6 weeks of liposomal amphotericin B is recommended. Unfortunately nephrotoxicity remains a problem in transplant patients treated with the lipid formulations, and may lead to renal failure.

Itraconazole is recommended for at least one year, initially at 200 mg three times daily for three days followed by 200 mg twice daily (40). Itraconazole blood concentrations should be measured to maintain levels between 1.0 and 10.0 µg/mL. Fluconazole is less effective and is not recommended unless itraconazole is contraindicated or not tolerated, and should be given at dose of 800 mg/day, adjusted for renal function. Voriconazole and posaconazole are active in-vitro against H. capsulatum, and have been used for treatment of histoplasmosis (14,15,30). H. capsulatum yeasts are resistant to the echinocandins (18,40), and may develop resistance to fluconazole and voriconazole (39).

Life-long suppressive therapy with itraconazole 200 mg daily, while effective for prevention of relapse, has several drawbacks. First, itraconazole may cause undesirable side effects, most commonly anorexia, vomiting or diarrhea, some of which may be serious, such as heart failure and hepatitis. Second, itraconazole interacts with several medications, most notably with calcineurin inhibitors in transplant patients. Third, itraconazole is relatively expensive. Suppressive therapy may not be necessary in many patients, however. The safety of stopping suppressive therapy was established in patients with AIDS who achieved immunological improvement during antiretroviral therapy (16). In another report, relapse did not occur in eight transplant patients who had received at least one year of itraconazole or voriconazole before stopping therapy (15). In another report, however, suppressive therapy was used in half of cases (6). Only two of the 22 cases at Indiana University received chronic suppressive therapy. Also, only two patients in this series relapsed, one who received only a six month course of itraconazole, and the other who was treated with fluconazole. More information is needed to define the criteria for stopping therapy and determine the safety of that strategy in transplant patients.

ENDPOINTS FOR MONITORING THERAPY

Antigenemia declines during the first month after starting amphotericin B treatment of disseminated histoplasmosis, followed by a decline in antigenuria. Monitoring antigen concentration may assist in decisions about stopping treatment. Discontinuation of therapy could be considered if antigenemia cleared and antigenuria was below 4 ng/mL. This approach was effective in a small cohort (N=8) of transplant patients (15), and in patients with AIDS (16).

PREVENTION OF HISTOPLASMOSIS FOLLOWING TRANSPLANTATION

Patient Education

Patients should be educated about their risk for acquiring histoplasmosis, including the types of environmental foci likely to be contaminated with H. capsulatum and activities associated with exposure (Table 2).

Pre-Transplant Patient Screening

Candidates for transplantation should be carefully evaluated for clinical findings suggestive of active histoplasmosis that might have occurred during the two years prior to transplantation (40). A history of pneumonia or systemic illness characterized by fever and weight loss or radiographic or CT scan abnormalities consistent with histoplasmosis (mediastinal lymphadenopathy, pulmonary nodules, and pulmonary infiltrates) would be the basis for testing to exclude histoplasmosis in patients who reside in or have traveled to endemic areas. In those with findings consistent with histoplasmosis, testing should include chest CT scan, serologic tests, and Histoplasma antigen in urine and serum. If the clinical and laboratory findings indicates that the patient might have had histoplasmosis during the last two years, itraconazole treatment for a few months before transplantation, if feasible, and 6 to 12 months following transplantation should be considered (40). However, screening for antigen or antibodies is not recommended as part of the routine pre-transplant evaluation. The incidence of active histoplasmosis following transplantation in an endemic area is below 0.5%. Assuming a sensitivity of 98% and specificity of 98% for the screening test, the positive predictive value would be 20%: only one in 5 individuals treated for a positive result could benefit, while four would be subjected to the adverse effects and drug interactions associated with itraconazole. Given the excellent sensitivity of antigen detection for rapid diagnosis, the outstanding outcome of antifungal therapy if the diagnosis is established promptly, and the adverse effects and drug-drug interactions with itraconazole, the risk to benefit ratio does not support routine screening.

Pre-Transplant Donor Screening

Several reports describe transplantation of organs from donors with undiagnosed active histoplasmosis resulting in rapidly progressive disseminated histoplasmosis in the organ recipients. Whenever possible, potential live donors should be evaluated for active histoplasmosis before organ donation. This evaluation should include assessment of clinical findings of active infection (fever, sweats, weight loss, cough) during the month prior to donation, radiographic or CT evaluation of the lungs (mediastinal lymphadenopathy or pulmonary infiltrates), clinical findings of disseminated histoplasmosis (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, skin lesions, mucosal lesions), and laboratory evidence for bone marrow suppression (anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia) or hepatitis (bilirubin or enzyme elevation). If findings for possible histoplasmosis are a present, additional testing should include Histoplasma antigen from urine and serum, Histoplasma serology, and fungal blood culture. If a living donor exhibited findings of active histoplasmosis, or of histoplasmosis any time in the past two years based upon clinical and radiographic findings, treatment should be administered for three to six months before organ donation. Additionally, recipients should be followed carefully for development of histoplasmosis during the next year, including tests for antigen in the urine and serum at three month intervals, and at the time of clinical illness consistent with histoplasmosis. Antifungal prophylaxis for the first three months following transplantation should also be considered if the donor had active histoplasmosis.

For deceased or living donors , organs should be inspected for lesions consistent granuloma at the time of procurement. Suspicious lesions should be examined by histopathology and fungal culture. The presence of miliary lesions should disqualify use of any organs from that individual. Occasional lesions would not disqualify the use of the organs, but demonstration of organisms consistent with H. capsulatum by histopathology or isolation by culture would be a basis for treatment of the recipient for histoplasmosis. If granuloma were observed, serum and urine from the donor should be tested for Histoplasma antigen and serum should be tested for anti-Histoplasma antibodies. Detection of antigen or antibodies would be a basis for treating the recipient for histoplasmosis.

Calcified and non-calcified lung nodules or mediastinal lymph nodes are common “incidental” findings in individuals from endemic areas for histoplasmosis, and usually do not indicate active infection (22,33,35,38). However, the incidence of histoplasmosis following transplantation of organs from donors with calcified lesions caused by histoplasmosis is unknown. Thus, an evidence-based recommendation for evaluation and management cannot be made in such cases. If workup for histoplasmosis is conducted, it should include microscopic examination and culture for fungus, antigen testing of urine and serum and testing for antibodies.

Prophylaxis in an Outbreak

If the rate of histoplasmosis among transplant patients was more than ten cases/100 patient-years, prophylaxis with itraconazole might be appropriate. This approach was shown to be effective in AIDS patients (25), and has been recommended in guidelines for management of histoplasmosis (40). However, even during large outbreaks, the rates were just two cases/100 patient years (41).

Vaccination

Although animal studies suggest that vaccination may protect against a fatal outcome following experimental infection, no studies have been conducted in humans, and the effectiveness of vaccination during immunosuppression is unknown. Presumably any naturally acquired immunity resulting from prior infection is lost due to the poor underlying health of patients with end-stage diseases for which transplantation was needed, or the immunosuppression required for successful transplantation. Vaccination for endemic mycoses has been reviewed (7).

INFECTION CONTROL

Histoplasmosis is not transmitted from patient to patient, and the mould is unlikely to exist in the hospital, outside the microbiology laboratory. Exposures in the laboratory are possible, and exposed individuals, especially those who may be immunocompromised, should be treated to prevent development of histoplasmosis.

REFERENCES

1. Assi MA, Sandid MS, Baddour LM, Roberts GD, and Walker RC. Systemic Histoplasmosis: A 15-Year Retrospective Institutional Review of 111 Patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2007; 86:162-9. [PubMed]

2. Ben Ami R, Lasala PR, Lewis RE, and Kontoyiannis DP. Lack of galactomannan reactivity in dematiaceous molds recovered from cancer patients with phaeohyphomycosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2010; 66:200-3. [PubMed]

3. Bhowmik D, Dinda AK, Xess I et al. Fungal panniculitis in renal transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis 2007. [PubMed]

4. Bialek R, Feucht A, Aepinus C et al. Evaluation of two nested PCR assays for detection of Histoplasma capsulatum DNA in human tissue. J Clin Microbiol 2002; 40:1644-7. [PubMed]

5. Connolly PA, Durkin MM, LeMonte AM, Hackett EJ, and Wheat LJ. Detection of histoplasma antigen by a quantitative enzyme immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2007; 14:1587-91. [PubMed]

6. Cuellar-Rodriguez J, Avery RK, Lard M et al. Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients: 10 years of experience at a large transplant center in an endemic area. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:710-6. [PubMed]

7. Cutler JE, Deepe GS, Jr., and Klein BS. Advances in combating fungal diseases: vaccines on the threshold. Nat Rev Microbiol 2007; 5:13-28. [PubMed]

8. Davies SF, Sarosi GA, Peterson PK et al. Disseminated histoplasmosis in renal transplant recipients. Am J Surg 1979; 137:686-91. [PubMed]

9. De Lavaissiere M, Manceron V, Bouree P et al. Reconstitution inflammatory syndrome related to histoplasmosis, with a hemophagocytic syndrome in HIV infection. J Infect 2008. [PubMed]

10. De Pauw B, Walsh TJ, Donnelly JP et al. Revised definitions of invasive fungal disease from the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer/Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group (EORTC/MSG) Consensus Group. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:1813-21. [PubMed]

11. Dossetor JB, Gault MH, Oliver JA, Inglis FG, MacKinnon K J, MacLean LD. Cadaver Renal Homotransplants: Initial Experiences. Can Med Assoc J 1964;91:733-742. [PubMed]

12. Dwyre DM, Bell AM, Siechen K, Sethi S, and Raife TJ. Disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as thrombotic microangiopathy 2. Transfusion 2006; 46:1221-5. [PubMed]

13. Egan L, Connolly P, Wheat LJ et al. Histoplasmosis as a cause for a positive Fungitell (1-->3)-beta-D-glucan test. Med Mycol 2008; 46:93-5. [PubMed]

14. Freifeld A, Proia L, Andes D et al. Voriconazole use for endemic fungal infections. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53:1648-51. [PubMed]

15. Freifeld AG, Iwen PC, Lesiak BL, Gilroy RK, Stevens RB, and Kalil AC. Histoplasmosis in solid organ transplant recipients at a large Midwestern university transplant center. Transpl Infect Dis 2005; 7:109-15. [PubMed]

16. Goldman M, Zackin R, Fichtenbaum CJ et al. Safety of discontinuation of maintenance therapy for disseminated histoplasmosis after immunologic response to antiretroviral therapy. Clin Infect Dis 2004; 38:1485-9. [PubMed]

17. Johnson PC, Wheat LJ, Cloud GA et al. Safety and efficacy of liposomal amphotericin B compared with conventional amphotericin B for induction therapy of histoplasmosis in patients with AIDS. Ann Intern Med 2002; 137:105-9. [PubMed]

18. Kohler S, Wheat LJ, Connolly P et al. Comparison of the echinocandin caspofungin with amphotericin B for treatment of histoplasmosis following pulmonary challenge in a murine model. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2000; 44:1850-4. [PubMed]

19. Lehan PH and Furcolow ML. Epidemic histoplasmosis. J Chron Dis 1957; 5:489-503. [PubMed]

20. Limaye AP, Connolly PA, Sagar M et al. Transmission of Histoplasma capsulatum by organ transplantation. N Engl J Med 2000; 343:1163-6. [PubMed]

21. Marques SA, Hozumi S, Camargo RM, Carvalho MF, and Marques ME. Histoplasmosis presenting as cellulitis 18 years after renal transplantation. Med Mycol 2008;1-4. [PubMed]

22. Mashburn JD, Dawson DF, and Young JM. Pulmonary calcifications and histoplasmosis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1961; 84:208-16. [PubMed]

23. Masri K, Mahon N, Rosario A et al. Reactive hemophagocytic syndrome associated with disseminated histoplasmosis in a heart transplant recipient. J Heart Lung Transplant 2003; 22:487-91. [PubMed]

24. McGuinn ML, Lawrence ME, Proia L, and Segreti J. Progressive disseminated histoplasmosis presenting as cellulitis in a renal transplant recipient. Transplant Proc 2005; 37:4313-4. [PubMed]

25. McKinsey DS, Wheat LJ, Cloud GA et al. Itraconazole prophylaxis for fungal infections in patients with advanced human immunodeficiency virus infection: randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Mycoses Study Group. Clin Infect Dis 1999; 28:1049-56. [PubMed]

26. Nucci M and Perfect JR. When primary antifungal therapy fails. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:1426-33. [PubMed]

27. Oh YS, Lisker-Melman M, Korenblat KM, Zuckerman GR, and Crippin JS. Disseminated histoplasmosis in a liver transplant recipient. Liver Transpl 2006; 12:677-81. [PubMed]

28. Okudaira M, Straub M, and Schwarz J. The etiology of discrete splenic and hepatic calcifications in an endemic area of histoplasmosis. Am J Pathol 1961; 39:599-611. [PubMed]

29. Qualtieri J, Stratton CW, Head DR, and Tang YW. PCR detection of Histoplasma capsulatum var. capsulatum in whole blood of a renal transplant patient with disseminated histoplasmosis. Ann Clin Lab Sci 2009; 39:409-12. [PubMed]

30. Restrepo A, Tobon A, Clark B et al. Salvage treatment of histoplasmosis with posaconazole. J Infect 2007; 54:319-27. [PubMed]

31. Sathapatayavongs B, Batteiger BE, Wheat J, Slama TG, and Wass JL. Clinical and laboratory features of disseminated histoplasmosis during two large urban outbreaks. Medicine (Baltimore) 1983; 62:263-70. [PubMed]

32. Sen D, Birns J, and Rahman A. Articular presentation of disseminated histoplasmosis. Clin Rheumatol 2007; 26:823-4. [PubMed]

33. Straub M and Schwarz J. The healed primary complex in histoplasmosis. Am J Clin Pathol 1955; 25:727-41. [PubMed]

34. Tang YW, Li H, Durkin MM et al. Urine polymerase chain reaction is not as sensitive as urine antigen for the diagnosis of disseminated histoplasmosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2006. [PubMed]

35. Ulbright TM and Katzenstein AL. Solitary necrotizing granulomas of the lung: differentiating features and etiology. Am J Surg Pathol 1980; 4:13-28. [PubMed]

36. Vail GM, Young RS, Wheat LJ, Filo RS, Cornetta K, and Goldman M. Incidence of histoplasmosis following allogeneic bone marrow transplant or solid organ transplant in a hyperendemic area. Transpl Infect Dis 2002; 4:148-51. [PubMed]

37. Wagner JD, Prevel CD, and Elluru R. Histoplasma capsulatum necrotizing myofascitis of the upper extremity. Ann Plast Surg 1996; 36:330-3. [PubMed]

38. Weydert JA, Van Natta TL, and DeYoung BR. Comparison of fungal culture versus surgical pathology examination in the detection of Histoplasma in surgically excised pulmonary granulomas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2007; 131:780-3. [PubMed]

39. Wheat LJ, Connolly P, Smedema M et al. Activity of newer triazoles against Histoplasma capsulatum from patients with AIDS who failed fluconazole. J Antimicrob Chemother 2006; 57:1235-9. [PubMed]

40. Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of patients with histoplasmosis: 2007 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 45:807-25. [PubMed]

41. Wheat LJ, Smith EJ, Sathapatayavongs B et al. Histoplasmosis in renal allograft recipients. Two large urban outbreaks. Arch Intern Med 1983; 143:703-7. [PubMed]

42. Wheat LJ, Hackett E, Durkin M et al. Histoplasmosis-Associated Cross-Reactivity in the BioRad Platelia Aspergillus Enzyme Immunoassay. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2007; 14:638-40. [PubMed]![]()

Figure 1. A Diagnostic Algorithm for Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis, Using Battery of Tests

Table 1. Summary of Findings in Indiana University Cases

| Transplant type | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Renal1 | 14 (63.6) |

| Liver | 4 (19.2) |

| Lung | 3 (13.6) |

| Heart | 1 (4.5) |

| Immunosuppressive drugs | |

| Calcineurin inhibitor (tacrolimus, cyclosporine A) | 22 (100) |

| Corticosteroids | 14 (63.6) |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | 3 (13.6) |

| Sirolimus | 1 (4.5) |

| Clinical classification | |

| Disseminated and pulmonary | 20 (91.9) |

| Pulmonary | 2 (8.1) |

| Diagnostic tests2 | |

| Antigen, urine | 22/22 (100) |

| Antigen, serum | 11/12 (91.7) |

| Culture | 12/21 (57.1) |

| Cytology, histopathology | 11/13 (84.6) |

| Serology | 2/10 (20) |

| Severity | |

| ICU | 7 (31.8) |

| Hospitalized | 15 (68.2) |

| Treatment, initial | |

| Amphotericn B | 15 (68.2) |

| Itraconazole | 7 (31.8) |

| Outcome | |

| Death | 0 (0) |

| Relapse | 2 (9.1) |

| Remission | 20 (90.9) |

| Chronic suppressive therapy | 2 (9.1%) |

2Not all tests were performed on every patient.

Table 2. Patient Assessment and Education

| Pre-transplant assessment | |

|---|---|

| 1. Possible exposure to Histoplasma (19) | |

| Sites likely to contain H. capsulatum | Activities likely to cause exposure to H. capsulatum |

Old buildings, farms, silo, church belfries, attics

Chicken house, bird roosts, bat habitatsWood lots, wood piles, dead treesCaves, storm cellarsSchool or prison courtyardsBridges |

Excavation, demolition, remodeling

Cleaning buildingsShoveling bird or bat manureCamping, gardening, diggingCutting, transporting, or burning woodRoutine activities near contaminated sites that are being disturbedTravel to parts of Latin America, especially if spelunking or outdoor activities near contaminates site |

| 2. Past diagnosis of histoplasmosis | |

| 3. Pneumonia in past 2 years | |

| 4. Fever and/or weight loss in past 3 months2 | |

| 5. Chest radiographic or CT abnormalities: lymphadenopathy, nodules, infiltrate | |

| Post-transplantation education and assessment | |

| 1. Avoid activities associated with exposure to Histoplasma | |

| 2. Tell your doctor about possible exposure | |

| 3. Tell your doctor about any new symptoms | |

| 4. Don’t put off contacting your doctor | |

1.Endemic areas include parts of the Midwestern United States, Mexico, Central and South America, Africa, and Asia.

2.Common symptoms include prolonged/unexplained fever, sweats. cough, fatigue, weight loss. Other symptoms include headaches, skin or mouth sores, abdominal pain, diarrhea, blood in your bowel movements. Of note is that this is not a complete list of symptoms of histoplasmosis, so tell your doctor about all of your symptoms. |

|

Swartzentruber S, Rhodes L, et al. Diagnosis of Acute Pulmonary Histoplasmosis by Antigen Detection. Clin Infect Dis. 2009 Dec 15;49:1878-82.

Guided Medline Search for

Wheat LJ. Histoplasma Capsulatum(Histoplasmosis)

Baron EJ. Mold

Singh, N., Perfect, J. Immune Reconstitution Syndrome Associated with Opportunistic Mycoses. The LANCET Infectious Diseases 2007; Vol.7, Issue 6, 395-401.

Gauthier G, et al. Insights into Fungal Morphogenesis and Immune Evasion. Microbe 2008;3(9):416-423.

Wheat LJ, Freifeld AG, Kleiman MB, et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Histoplasmosis: 2007 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:807-825.

Hage CA, et al. A Multicenter Evaluation of Tests for Diagnosis of Histoplasmosis. Clin Infect Dis 2011;53:448-454.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR RECENT REVIEWS

The Discovery of Histoplasmosis. 2013

Hagan T. Discovery and Naming of Histoplasmosis: Samuel Taylor Darling, 2010

Hagan T. Histoplasmosis in the U.S., 2010

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR HISTORICAL ASPECTS

Histoplasmosis in Solid Organ Transplant Patients