Community Acquired Pneumonia

Authors: Julio A. Ramirez

PATHOGENESIS

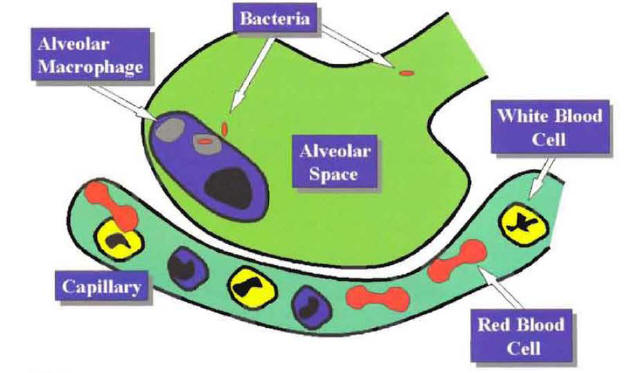

Pneumonia indicates an inflammatory process of the lung parenchyma caused by a microbial agent. The most common pathway for the microbial agent to reach the alveoli is by microaspiration of oropharyngeal secretions. Once microorganisms reach the alveolar space, they cause pneumonia by overcoming the last defense mechanism of the lung, the alveolar macrophage. Most of the time, the alveolar macrophage phagocytizes and kills the microorganisms that reach the alveolar space. This explains why even though the arrival of microorganisms into the alveolar space is a not-infrequent occurrence, the presence of clinical pneumonia is infrequent (Figure 1).

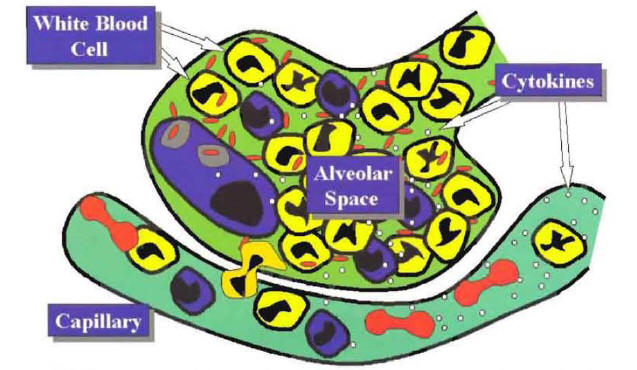

If the alveolar macrophage is unable to control the growth of the microorganisms, then, as a final protective defense mechanism, the lungs develop a local inflammatory response. This local inflammatory response is characterized by movement of white blood cells, lymphocytes and monocytes from the capillaries into the alveolar space (Figure 2).

The recruitment of phagocytic cells to the alveolar space is primarily mediated by tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and interleukin-l (IL-I) produced by the alveolar macrophages. In addition to TNF and IL-I, other important locally produced cytokines include IL-6, IL-10, IL-12, monocyte chemotaxin protein-l and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (1). Once these cytokines reach the systemic circulation, they also produce a systemic inflammatory response. The local and systemic inflammatory response is responsible for the majority of the signs, symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities that characterize the community-acquired pneumonia a (CAP) syndrome

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The patient with pneumonia syndrome will present with cough, sputum production, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, fever, chills. Tachycardia, tachypnea, rales, and signs of consolidation on physical examination, leukocytosis, left shift, and a new pulmonary infiltrate on chest x-ray. Several of these abnormalities are due to the local inflammatory response produced by the arrival of white blood cells into the alveolar space. The development of cough and sputum production are due to the excess of white blood cells in the alveoli. The shortness of breath and hypoxemia are secondary to the accumulation of cells in the alveolar space, producing a ventilation-perfusion mismatching. The presence of a new pulmonary infiltrate at chest x-ray is predominantly due to the buildup of inflammatory cells in the alveoli (Figure 3).

Other manifestations of the pneumonia syndrome are due to the systemic inflammatory response. The presence of fever is primarily mediated by the action of IL-1 and other mediators that act on the thermoregulatory center at the level of the hypothalamus. The presence of leukocytosis and left shift is primarily mediated by the action of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor on the bone marrow (Figure 3). Owing to the low sensitivity and specificity, history and physical examination are considered suboptimal to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of CAP (2). National guidelines recommend that a new pulmonary infiltrate at chest x-ray should be present to classify a hospitalized patient as having the diagnosis of CAP (3,4). The clinical diagnosis requires evidence of a new pulmonary infiltrate compatible with pneumonia associated with other signs and symptoms characteristic of the pneumonia syndrome. Because the clinical diagnosis of CAP is based on a clinical syndrome, it is expected that in some hospitalized patients with a clinical diagnosis of CAP, an alternative diagnosis will explain the signs and symptoms of the patient. Although the patient may have cough, sputum production and fever, sometimes the infection represents not pneumonia but an acute exacerbation of chronic bronchitis or acute bronchitis. In this type of patient, there will be no evidence of a new pulmonary infiltrate. In patients with a pulmonary infiltrate at admission to the hospital, the infiltrate may be not a new infiltrate but a chronic one representing old pulmonary changes. In some patients with a new pulmonary infiltrate, it may be due to an alternative diagnosis such as pulmonary embolism. In a study performed in our institution, we found that the most common clinical scenario associated with misdiagnosis of CAP is the patient admitted to hospital with cough and a new pulmonary infiltrate due to an exacerbation of congestive heart failure (5).

REFERENCES

1. Nelson S, Mason CM, Kolls J. Summer WR: Pathophysiology of pneumonia. Clin Chest Med 1995;16:1-123. [PubMed]

2. Wipf JE, Lipsky BA, Hirschmann JV, et al: Diagnosing pneumonia by physical examination: relevant or relic? Arch Intern Med 1999: 159: 1082-1 OR? [PubMed]

3. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

4. Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

5.Ahkee S, Barzallo M, Ramirez J. Empiric antibiotic therapy in patients without documented infection. Infect Med 1996;13:800-802, 823.[PubMed]

6.Wheeler JH, Fishman EK. Computed tomography in the management of chest infections: current status. Clin Infect Dis 1996;23:232-240. [PubMed]

DECISION FOR SITE OF CARE

During the initial evaluation of the patient with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP), the physician needs to define the patient's severity of disease and the intensity of care that will be necessary for the patient to achieve an optimal outcome. If the level of care the patient can receive at home is not sufficient, the patient will require hospitalization. Hospitalization will permit the use of intravenous antibiotics, intravenous fluids, hemodynamic support, supplemental oxygen, mechanical ventilation, and aggressive therapy of comorbidity and will facilitate several clinical evaluations performed by nurses and physicians during the day.

Hospitalization Based on Patient’s Risk for Complicated Course

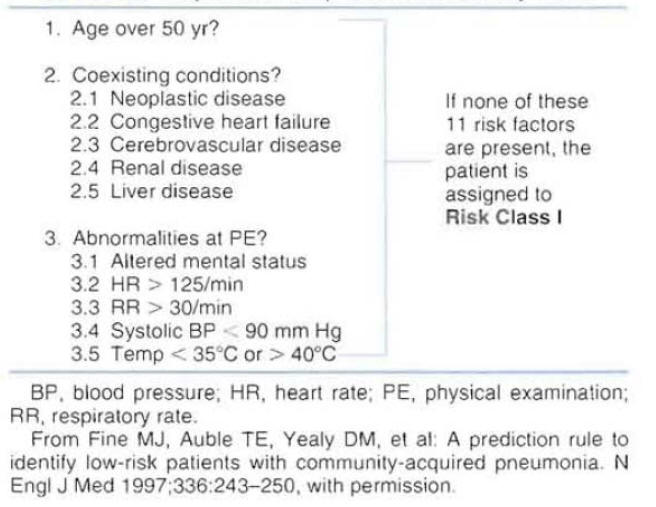

In an attempt to help physicians in the evaluation of patient's severity of disease and risk for mortality, the American Thoracic Society published a list of criteria associated with poor outcome in patients with CAP (Figure 4) (1).

The document indicates that hospitalization can be based on the number of criteria for complicated course identified in a patient. It is suggested that a patient with more than one criteria for complicated course will benefit from hospitalization.

Hospitalization Based On Patient’s Risk for Mortality

A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with CAP was derived using data from 14,199 adults with CAP (2). To parallel physician decision-making processes, the prediction rule was developed in two steps.

REFERENCES

1. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

2.Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al: A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia. N Engl J Med 1997;336:243-250. [PubMed]

3. Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

MICROBIOLOGIC WORK UP

Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

In clinical studies designed to identify the etiology of CAP using reference microbiology laboratories, a specific pathogen is not identified in approximately 50 percent of the patients (1,2). In everyday practice, clinicians are expected to encounter pneumonia of unknown etiology in more than half of the hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP). The etiology of CAP can be classified into four groups: (a) CAP caused by typical or conventional bacteria, (b) CAP caused by atypical bacteria, (c) CAP caused by other agents, and (d) CAP of unknown etiology. The incidence of the most common organisms causing CAP, according to a review of the international literature performed by the author is presented in Table 1

The Importance of Defining the Etiology of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Defining the etiology of pneumonia may have significant implications for patient management. In patients who are clinically improving after initiation of broad-spectrum empiric therapy, knowing the etiology may allow streamlining the regimen with therapy directed to the identified pathogen. Antibiotic streamlining may prevent selection of resistant bacteria and decrease cost of therapy. In the hospitalized patient with pneumonia who suffers clinical deterioration after initial empiric therapy, defining the etiology of pneumonia may explain the reason for the deterioration, help in the selection of alternative therapy, and improve clinical outcome. Other potential benefits of defining the etiology of CAP include the appropriate isolation of patients infected with pathogens that can be transmitted to other patients or health care personnel (e .g., Mycobacterium tuberculosis, influenza virus).

Clinical Microbiology Testing

In an attempt to determine whether a typical pathogen is the etiology of pneumonia, it is recommended that all patients should have a sputum specimen for Gram stain and culture as well as two sets of blood cultures obtained before the institution of antimicrobial therapy (1,2). The quality of sputum specimen should be determined by Gram stain results. Only sputum specimens that contain good numbers of leukocytes and minimal numbers of epithelial cells per low-power field should be accepted for bacterial culture. Most national guidelines consider that a sputum sample for Gram stain, culture and sensitivity, and blood cultures should be obtained in all hospitalized patients. The Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) recommends the urinary antigen test for detection of Legionella pneumophila in patients with severe CAP who are hospitalized in the intensive care unit (lCU) (2). (We recommend it for all patients including ambulatory patients).

REFERENCES

1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

2. Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

3. Yu VL, Stout JE. Community-acquired legionnaires disease: implications for underdiagnosis and laboratory testing. Clin Infect Dis 2008;46:1356-1364. [PubMed]

EMPIRIC ANTIMICROBIAL THERAPY

Classification of Patients

The American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) have proposed very similar guidelines for the selection of empiric antimicrobial therapy of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) (1,2). Patients are initially classified in two groups according to severity of disease and site of care in the hospital. One group is composed of patients with moderate pneumonia who are hospitalized in the general medical ward; and the other includes patients with severe pneumonia who are hospitalized in intensive care units (ICUs).

Patients Hospitalized in the General Medical Ward

According to the ATS/IDSA guidelines, patients admitted to a general ward can be classified in two groups based on the presence of risk factors for penicillin-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae and enteric gram-negative rods. Those considered at risk of infection with penicillin-resistant organisms include the elderly, patients with multiple medical comorbidities, patients with recent use of beta lactam antibiotics, patients who are immunosuppressed, or patients in contact with a child in day care. The same factors are considered to place a patient at risk for infection with macrolide-resistantS. pneumoniae. Risk factors for the presence of enteric Gram-negative organisms include the recent use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, the use of high-dose steroids, multiple medical comorbidities, and recent hospitalization.

Patients Hospitalized in the General Ward without Risk Factors of Resistant Organisms

Two types of regimens can be considered appropriate for initial empiric therapy for the hospitalized patient in the general ward without risk factors for the presence of resistant organisms. One regimen consists of monotherapy with a new-generation macrolide antibiotic; the other regimen consists of monotherapy with an anti-streptococcal quinolone. The most common organisms causing CAP in this group of patients and the most commonly used antibiotics for empiric therapy are presented in Figure 6.

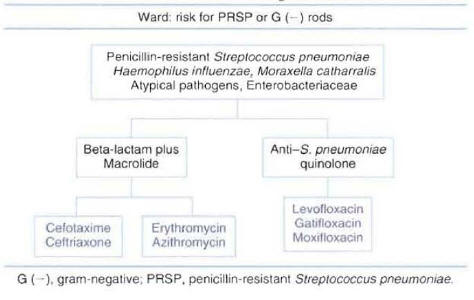

Patients Hospitalized in the General Ward with Risk Factors for Resistant Organisms

Two types of regimens can be considered appropriate for initial empiric therapy for the hospitalized patient in the general ward with risk factors for the presence of resistant organisms. One regimen consists of combination therapy with a beta-lactam antibiotic with good activity against resistant S. pneumoniae plus a macrolide antibiotic; the other regimen consists of monotherapy with an anti-streptococcal quinolone. The most common organisms causing CAP in this group of patients and the most commonly used antibiotics for empiric therapy are presented in Figure 7.

Patients Hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit

Patients admitted to intensive care should be subclassified in two groups according to the presence of risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) complicated with bronchiectasis or patients with COPD and chronic use of broad-spectrum antibiotics can be colonized with gram-negative rods, includingP. aeruginosa. When these patients are hospitalized to the ICU with severe CAP, they should be considered at risk forP. aeruginosainfection.

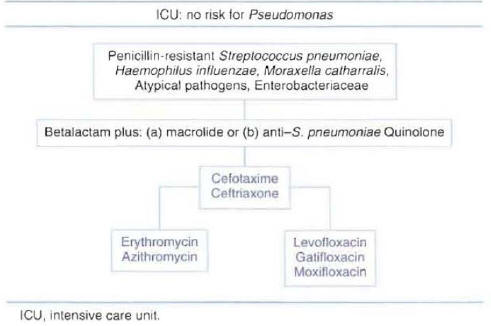

Patients Hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit without Risk Factors for Pseudomonas :Two types of regimens can be considered appropriate empiric therapy for patients without risk factors forPseudomonasinfection. One regimen consists of a combination of beta-lactam antibiotic plus a macrolide; the other consists of a combination of beta-lactam antibiotic plus an anti-streptococcal quinolone. The beta-lactam antibiotic should have good activity against resistant pneumococci. Selecting a beta-lactam antibiotic with good activity against P. aeruginosa in this group of patients is not necessary. The lack of recommendation in national guidelines for the use of empiric therapy with a quinolone as monotherapy in this group of patients is due to a lack of clinical studies in patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICU. The most commonly used antibiotics recommended for each regimen are presented in Figure 8.

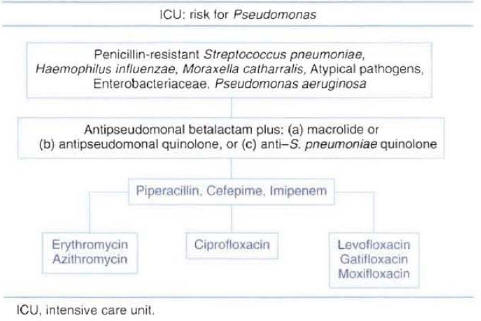

Patients Hospitalized in the Intensive Care Unit with Risk Factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa :Three types of regimens can be considered appropriate therapy for patients with risk factors for Pseudomonas infection. All regimens include an antipseudomonal beta-lactam antibiotic that can be combined with an anti-pseudomonal quinolone, or a macrolide, or an antistreptococcal quinolone. The selected beta-lactam should have activity againstP. aeruginosaand should maintain activity against resistant pneumococci. The most commonly used antibiotics recommended for each regimen are presented in Figure 9. The addition of single daily dose aminoglycoside is sometimes recommended until the presence ofP. aeruginosapneumonia with bacteremia has been ruled out.

Timing of Antibiotic Administration

Recent data in the management of CAP indicate that delay in the initiation of anti-infective therapy is associated with longer hospital stay and decreased patient outcome (3). Thus, it is suggested that hospitalized patients with CAP should have prompt initiation of empiric therapy.

A delay in administration of antibiotic may be secondary to a delay from a patient waiting to be seen by a physician after the patient arrived at the emergency room or a delay in the administration of antibiotics after the diagnosis of CAP was already performed.

REFERENCES

1. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

2. Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

3.Meehan TP, Fine MJ, Krumholz HM, et al. Quality of Care, process and outcomes in elderly patients with pneumonia. JAMA 1997:278:2080-2084. [PubMed]

CLINICAL STABILITY

Pneumonia Recovery Phase

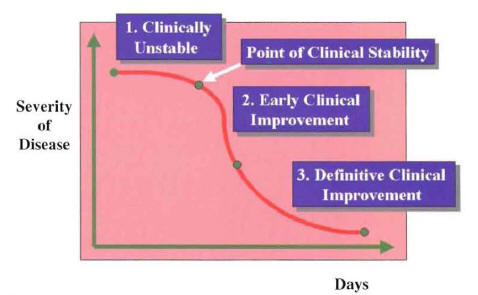

After initiation of intravenous empiric therapy, the majority of hospitalized patients will enter a recovery phase that will end with the clinical cure of the patient and the eradication of the pathogen. The recovery phase of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) can be divided into three different periods (Figure 10) (1). The first period starts with the initiation of antimicrobial therapy. During this first period, the patient is clinically unstable. The initial antimicrobial regimen should not be changed within this first period, unless there is a marked clinical deterioration. Even with appropriate empiric antimicrobial therapy, the majority of patients will remain clinically unstable for 48 to 72 hours. This first period ends when the patient reaches the point of clinical stability. During the second period, the patient shows evidence of initial clinical improvement. The signs, symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities caused by the infection begin to normalize. This second period of initial clinical improvement may last 24 to 48 hours. The third period is characterized by a definitive clinical improvement. During this period of recovery, the signs, symptoms, and laboratory abnormalities are greatly improved. This period occurs in the majority of patients after 5 days of hospitalization. This last period ends at the point of complete resolution of signs and symptoms, when the patient is considered clinically cured. National guidelines from the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Diseases Society (IDSA) suggest that in patients who are clinically improving, the initial intravenous therapy can be switched to oral therapy (switch therapy) (2,3).

Criteria for Clinical Stability and Switch Therapy

The traditional approach to therapy of hospitalized patients with CAP has been the use of intravenous antibiotics during the entire recovery phase until the patient achieved definitive clinical improvement. At this point, usually after several days of hospitalization, the intravenous antibiotics were discontinued and the patient was discharged from the hospital.

With the switch therapy approach, one needs to identify the point of clinical stability during the recovery phase. At this point, when the patient is entering the period of initial clinical improvement, intravenous antibiotics are switched to oral antibiotics (Figure 11).

A patient can be considered to reach the point of clinical stability when these three criteria are met: (a) cough and shortness of air are improving, (b) the patient is afebrile for at least 8 hours, (c) the white blood cell count is normalizing, A fourth criteria, adequate oral intake and gastrointestinal absorption, should be met for a patient to be considered a switch therapy candidate. As soon as a patient meets the four switch therapy criteria, intravenous antibiotics can be safely switched to oral antibiotics (4,5). Switch therapy can be safely performed even in patients with documented pneumococcal bacteremia at the time of hospital admission (6).

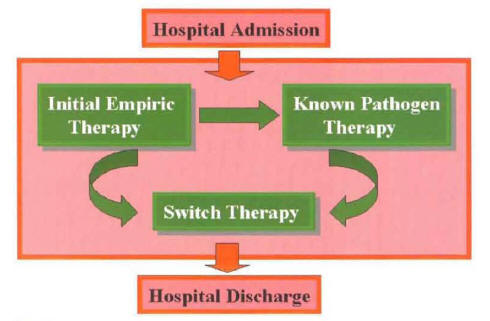

Oral Antimicrobial Therapy

In hospitalized patients with CAP, the etiologic agent remains unknown in more than half of the cases. Because of this, the most common scenario in the management of CAP is it switch to oral antibiotics from empiric parenteral therapy (Figure 12).

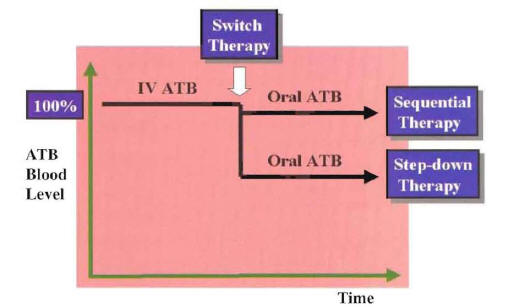

In this clinical situation, the oral antimicrobial should be equivalent to the intravenous empiric regimen with regard to spectrum of antimicrobial activity. If more than one oral antimicrobial is able to match the microbiologic activity of the intravenous regimen, the drug with the best pharmacokinetic profile is selected. In patients with a known pathogen, the choice of the oral antimicrobial for switch therapy is based on the susceptibility pattern of the identified microorganism. In this clinical situation, the switch to oral antimicrobials is made from known pathogen therapy. If more than one oral antimicrobial is active against the etiologic agent, the antimicrobial with the narrowest spectrum of activity and best pharmacokinetic profile is chosen. Considering the antibiotic blood level achieved with the oral antibiotic in relation to that of the intravenous antibiotic, the switch to oral therapy can be defined as sequential therapy or step-down therapy (Figure 13).

If the oral antibiotic achieved almost the same level as the intravenous formulation, the switch can be defined as sequential therapy (e.g., switch to oral quinolone antibiotic). If the oral antibiotic achieved a lower concentration than the intravenous formulation, the switch can be defined as step-down therapy (e.g., switch to oral macrolide or cephalosporin antibiotic). Good clinical outcome has been demonstrated with switch therapy using the sequential or step-down approach.

REFERENCES

1. Ramirez JA. Switch therapy ill adult patients with pneumonia. Clin Pulm Med. 1995;2:327-333. [PubMed]

2. Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

3. Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

4.Ramirez JA, Srinath L, Ahkee S, et al: Early switch human intravenous to oral cephalosporins in the treatment of hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1273-1276. [PubMed]

5.Ramirez JA, Vargas S, Ritter GW, et al: Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge. Arch Intern Med 1999;159:2449-2454. [PubMed]

6. Ramirez JA, Bordon J: Early switch from intravenous to oral antibiotics in hospitalized patients with bacteremic Streptococcus pneumoniae community-acquired pneumonia. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:848-850. [PubMed]

MONITORING CLINICAL RESPONSE

A documented good clinical response to antibiotic therapy is one of the primary criteria in considering a patient ready for hospital discharge. The same criteria used to define when a patient is a candidate for switch therapy can be used to document a good clinical response.

From the group of hospitalized patients with good clinical response, some patients are candidates for hospital discharge the same day they are candidates for switch therapy, but a group of patients may need to continue in the hospital owing to other justified reasons even after they are switched to oral therapy

Length of Stay Related to Community-Acquired Pneumonia

The most common scenario for hospitalized patients with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) is a rapid clinical improvement after initiation of appropriate empiric therapy. The great majority of these patients can be switched to oral therapy and discharged from the hospital to complete the course of therapy at home (1). Once a patient is switched to oral therapy, there is no need to maintain the patient in the hospital for a period of observation to evaluate the clinical response to oral therapy (2).

Because length of hospitalization is not influenced by any other factor outside of the pulmonary infection, patients are considered to have length of stay related only to pneumonia. In this type of patient, the length of hospital stay can be considered inappropriate if the switch to oral antibiotic was delayed more than 24 hours after the patient was considered a candidate for switch therapy or if the patient remains hospitalized for clinical observation in oral therapy.

Length of Stay Related to Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Some hospitalized patients will improve clinically and may be switched from intravenous to oral therapy but will need to remain hospitalized for other reasons (1). Considering the possible clinical scenarios, these types of patients can be classified in three groups.

Group 1:Treatment of Comorbidity. This group consists of patients who require medical treatment of a previous or new medical condition that worsened as a consequence of the pulmonary infection. No need for treatment of comorbid conditions is a well-established criteria for hospital discharge (3). An example of deterioration of a previous medical condition is a patient with a well-known history of diabetes who developed severe metabolic abnormalities as a consequence of the pulmonary infection and may require hospital care even after the switch to oral therapy. An example of a new medical condition is a patient with a history of coronary artery disease who developed a new myocardial infarction after hospitalization. The patient may have a good clinical response of the pulmonary infection but needs to remain in the hospital for management of the myocardial infarction.

Group 2: Diagnostic Workup. This group consists of patients in whom it is necessary to perform a diagnostic workup of a new medical condition that developed during the treatment of pulmonary infection. Examples include a patient with CAP complicated with a new episode of gastrointestinal bleeding who may need to remain hospitalized for an endoscopic examination to define the etiology of the bleeding; or a patient with a new onset of cardiac arrhythmia who may require a diagnostic workup with a 24-hour Holter monitor.

Group 3:Social Needs. This group consists of patients who, from the point of view of their medical problems, are clinically stable and ready to continue therapy outside of the hospital, but they have social needs that prevent hospital discharge. An example is an elderly patient with CAP who lives alone, without any help from family or friends, who may be required to remain in the hospital until appropriate social support can be obtained.

Patients in any of these three groups have a justified reason to remain hospitalized even after clinical improvement of pulmonary infection has been documented. In these patients, the length of hospital stay will not be considered related only to CAP but also to other medical or social conditions.

Criteria for Hospital Discharge

Taking into account all these clinical scenarios, a patient can be considered a candidate for hospital discharge when these four criteria are met: (a) The patient is a candidate for switch therapy, (b) there is no need to treat comorbidity in the hospital setting, (c) there is no need for diagnostic workup in the hospital setting, and (d) the patient has no social needs. Patients should be discharged home on the day they meet these four criteria.

REFERENCES

1. Ramirez JA. Vargas S, Ritter GW, et al: Early switch from intravenous oral antibiotics and early hospital discharge. Arch Intern Med 1999:159:2449-2454. [PubMed]

2.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

3.Rhew DC, Tu GS, Ofman J, et al. Early switch and early discharge strategies in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. A meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2001; 161:722-727. [PubMed]

4.Fine MJ, Pratt HM, Obrosky S. et al: Relation between length of hospital stay and costs of care for patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Am J Med 2000;109:378-385. [PubMed]

MONITORING CLINICAL OUTCOME

During the clinical course of a patient with CAP, different times can be selected for evaluation of outcome. Clinical outcome can be evaluated at the time of hospital discharge. At this point, the patient with improvement of infection can be classified as clinical success, and the patient who died during hospitalization is classified as clinical failure. Evaluation of patient outcome at the time of hospital discharge is the simple way to evaluate and document clinical outcome. The problem with this form of evaluation is the inability to document a relapse of pneumonia or even death after discharge unless the patient is hospitalized in the same institution.

The ideal methodology to evaluate final clinical outcome is to examine all patients 3 to 4 weeks after therapy. At that point, a patient with resolution or improvement of infection is classified as clinical success, and a patient who died is classified as clinical failure. This outcome is sometimes difficult to capture owing to the need of a clinic visit for all patients. A follow-up telephone interview can simplify the evaluation of clinical outcome at 3 to 4 weeks after therapy.

The advantage of looking at final patient outcome is that outcome is evaluated at only one point in the clinical course of the disease, and the definitions used to classify a patient as clinical success or failure can be clearly delineated. One disadvantage of looking at outcome at the time of discharge or 3 to 4 weeks after therapy is that most of the resource utilization in hospitalized patients with CAP is related to the patient outcome during the first 7 days of hospitalization. Theoretically, a group of patients who at 30 days have an equal clinical successful outcome may have a very different resource utilization if there is a significant difference in clinical outcome during the initial days of hospital therapy.

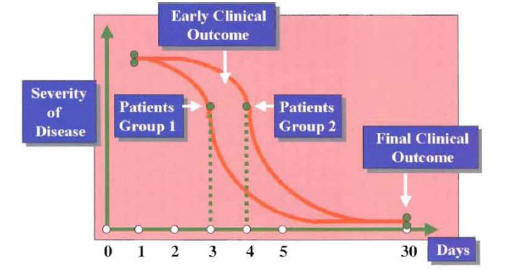

Figure 14 depicts an example of a series of patients treated with one antibiotic (group 1) who have the same clinical success at 30 days when compared with a group of patients treated with a different antibiotic (group 2). Although the clinical outcome at 30 days is equivalent, there is a significant difference among the groups regarding early clinical outcome. Because early clinical response is associated with early switch to oral therapy and early hospital discharge, the resource utilization for group I is significantly less. If only final outcomes are to be evaluated, this important difference among groups will not be appreciated.

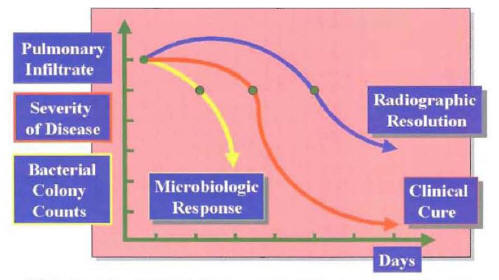

Early clinical outcomes are necessary to define the most cost-effective antimicrobial therapy. An antibiotic regimen that produces an earlier microbiologic resolution will be followed by an earlier clinical resolution. The correlation in the patterns of microbiologic response, clinical response, and radiographic response in patients with CAP is depicted in Figure 15.

If an institution is interested in evaluation of early clinical outcome, the clinical condition of the patient needs to be reviewed during the first days of hospitalization. To define early patient outcome, it is important to have a simple classification of the initial clinical course of hospitalized patients with CAP.

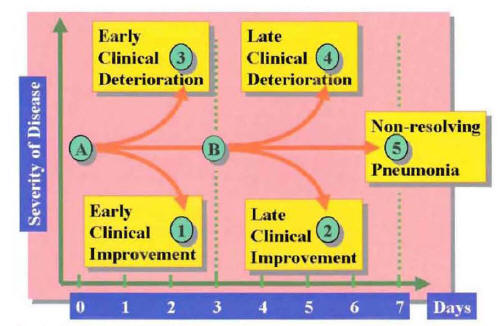

CLINICAL COURSE

After initiation of appropriate empiric therapy, the majority of hospitalized patients with CAP show evidence of clinical improvement by day 3 of treatment (1,2). In some patients, the first evidence of clinical improvement may be delayed beyond 3 days owing to host or pathogen factors. In contrast to this frequent clinical course is a group of patients who, after initial antibiotic therapy, enter a phase of clinical deterioration. Clinical deterioration may occur early, during the first 3 days of therapy, or late, after 3 days of therapy. Some patients remain without significant changes in clinical status, without improvement or deterioration, beyond the first 7 days of hospitalization. Based on this clinical response to therapy, the clinical outcome of patients with CAP may be categorized by day 7 of hospitalization into patients with early clinical response (group 1 of Figure 16), patients with late clinical response (group 2 of Figure 16), patients with early clinical deterioration (group 3 of Figure 16), patients with late clinical deterioration (group 4 of Figure 16), and patients with nonresolving CAP (group 5 of Figure 16).

Criteria for Clinical Improvement

In our institution, patients are considered to reach clinical improvement at the point they reach clinical stability and are candidates for switch therapy. Then, the clinical outcome is considered as clinical improvement when these three criteria are met: (a) cough and shortness of air are improving, (b) the patient is afebrile for at least 8 hours, and (c) the white blood cell count is normalizing. If criteria are met during the first 3 days of hospitalization, the outcome is classified as early clinical improvement. If criteria are met from days 4 to 7, the outcome is classified as late clinical improvement.

Criteria for Clinical Deterioration

Several parameters can be evaluated daily to assess response to therapy. The most commonly used are respiratory symptoms, fever, white blood cell count, pulmonary function, and hemodynamic function. Some patients develop a clear picture of clinical deterioration, requiring respiratory and hemodynamic support in a critical care unit. Then, the need for mechanical ventilation or transfer to an intensive care unit can be used as criteria to define clinical deterioration. Because a large number of patients who suffer clinical deterioration do not require mechanical ventilation or transfer to an intensive care unit, we have developed five criteria to define clinical deterioration based on the patient's symptoms, temperature, white blood cell count, pulmonary function, and hemodynamic function. The five criteria are:

1.Deterioration of Symptoms:manifested as increased cough, sputum, shortness of air, or pleuritic chest pain compared to the day before.

2.Deterioration of Fever:manifested as an increase greater than 2° F from the previous clay's maximal temperature.

3.Deterioration of the White Blood Cell Count:manifested as an increase greater than 20 percent of leukocytes or greater than 50 percent in bands compared to the day before. Deterioration of pulmonary function: manifested as increased respiratory rate greater than 50 percent, decreased PaO2 greater than 5 mmHg with the same FiO2, an increase in FiO2 greater than 10 percent to maintain greater than 90 percent saturation, or a decrease in PaO2/FiO2 greater than 20 percent compared with the day before.

4.Deterioration of Hemodynamic Function: manifested as a heart rate greater than 20%, a reduction in systolic blood pressure greater than 40 mmHg, or a deterioration of systolic blood pressure below 90 mmHg, or the use of pressors to maintain the same blood pressure as the day before.

After hospital admission, patients who in the same day fulfill two or more of these five criteria are considered to have clinical deterioration. If two or more criteria are met during the first 3 days of hospitalization, the outcome is classified as early clinical deterioration. If criteria are met from days 4 to 7, the outcome is classified as late clinical deterioration.

Classification of Clinical Deterioration

Onepossible reason for failure to respond to therapy in hospitalized patients with diagnosis of CAP is that the clinical diagnosis of pneumonia was incorrect (1,2). Some examples of clinical diagnosis that may be confused initially with CAP include obstructing bronchogenic carcinoma, lymphoma, intrapulmonary bleeding, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, and drug-induced pulmonary disease (e.g., amiodarone). A patient diagnosed with a noninfectious illness should be excluded from clinical outcome evaluation.

In patients with a correct diagnosis of CAP, the clinical deterioration can be classified in two groups, taking into consideration the antibiotic coverage of the initial empiric therapy: one group of patients with deterioration owing to inappropriate antimicrobial therapy, and a second group of patients with clinical deterioration even with appropriate antimicrobial therapy, Several etiologies can explain deterioration in each of the groups.

Clinical Deterioration Owing to Inappropriate Antimicrobial Therapy

Even in patients with selection of antibiotic therapy in accordance to guidelines, the antibiotic may not cover the etiologic agent of CAP owing to the presence of an organism with unusual susceptibility (e.g. MRSA) or the presence of an unusual organism (1,2). For some patients, an episode of CAP may be the first manifestation of an unrecognized immunodeficiency owing to human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, malignancy, or other underlying disease, and the etiology of CAP may be an unusual organism that will not be appropriately covered with the standard empiric therapy recommended in the hospital guidelines (e.g. Pneumocystis cariniipneumonia [PCP] in a patient with unrecognized acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]). In an attempt to identify an organism resistant to the initial antimicrobial therapy, all patients with clinical deterioration should have a more extensive microbiologic workup, The workup may include a pulmonary sample obtained by bronchoscopy with bronchoalveolar lavage.

Clinical Deterioration with Appropriate Antimicrobial Therapy

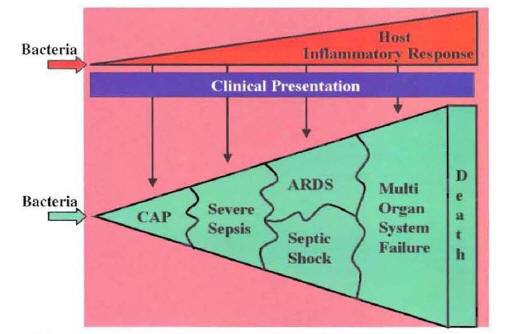

Clinical deterioration may occur in patients infected with common pathogens that are susceptible to the selected empiric antibiotics. For example, clinical deterioration may occur in a patient infected with a susceptible Streptococcus pneumoniae who was started on appropriate empiric therapy. These are patients with severe pneumonia in whom the systemic inflammatory response to the pulmonary infection progresses even when they were started on appropriate therapy (1,2). These patients admitted to the hospital with diagnosis of CAP will evolve into a clinical picture of severe sepsis, acute respiratory distress syndrome, septic shock, multi-organ failure, and death (Figure 17).

The progression from CAP to severe sepsis ending with multi-organ failure due to an uncontrolled host inflammatory response is a common etiology of clinical deterioration in hospitalized patients with CAP.

Other causes of clinical deterioration in patients with appropriate antibiotic therapy of the pulmonary infection include a metastatic infection (e.g., empyema, pericarditis), a superimposed nosocomial infection (e.g., sinusitis, urinary tract infection), or a superimposed medical complication (e.g,. pulmonary embolism,myocardial infarction).

EVALUATION OF LOCAL PRACTICE

Patients who warrant scrutiny for follow-up care includes those infected by more virulent microbes: Streptococcus pneumoniae, S. aureus, Legionellaspecies and those with underlying co-morbid or immunosuppressive illnesses (Table 2). Relapse may be more likely so we encourage these high risk patients to call the physician at any sign of fever or return of symptoms.

Evaluation of final outcome requires a patient visit to a clinic or a telephone contact. In the clinical situation in which the patient does not return for a scheduled follow-up clinic visit and the patient cannot be contacted by telephone, the lack of documented final outcome is considered as a justified variance from recommended care.

REFERENCES

1.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

2.Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

PNEUMONIA PREVENTION

Influenza and Pneumococcal Vaccines

During epidemics of influenza, there is an increase in the frequency of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to primary influenza pneumonia as well as secondary bacterial pneumonia complicating a case of influenza. Influenza vaccine is effective in limiting the severity of disease caused by the influenza virus. The pneumococcal vaccine has been proved to prevent pneumococcal pneumonia in young adults. The efficacy of the vaccine tends to decline with age and in patients who are immunocompromised.

The population of hospitalized patients with CAP should be consider a high-risk population for re-hospitalization related to influenza or pneumonia. All national guidelines consider that hospitalized patients with CAP should be evaluated to define whether they are candidates for vaccination, and candidates should be vaccinated before hospital discharge (1,2).

There is no contraindication for the use of the pneumococcal vaccine and the influenza vaccine following an episode of CAP. These vaccines can be given simultaneously at different sites, without increasing side effects (3).

When patients are hospitalized during the influenza season, they can be considered at risk of acquiring influenza from an infected health care worker. The vaccination of health care workers can be seen as an important strategy for the prevention of influenza in vulnerable hospitalized patients. Influenza vaccination of health care workers has been suggested as a pneumonia quality indicator (4).

SMOKING CESSATION

Because smoking is a definitive risk factor for the acquisition of pneumonia, all hospitalized patients with CAP should be advised to be enrolled in a smoking cessation program in an attempt to prevent relapse of pneumonia. Members of the hospital CAP team should be aware of the recent pharmacological and behavioral therapies that have been used to assist smokers in overcoming their addiction (5). Smoking cessation programs should be offered to all smokers.

QUALITY INDICATORS

Proportion of Patients Evaluated for or Given Pneumococcal Vaccine

The proportion of patients evaluated for or given pneumococcal vaccine can be used as a quality indicator. For this indicator, the numerator is the total number of patients evaluated for or given pneumococcal vaccination, and the denominator is the total number of patients discharged with CAP. The goal is to improve quality by preventing a new episode of pneumococcal CAP.

Proportion of Patients Evaluated for or Given Influenza Vaccine

The proportion of patients evaluated for or given influenza vaccine can be used as a quality indicator. For this indicator, the numerator is the total number of patients that who were evaluated for of or given influenza vaccine, and the denominator is the total number of discharged patients with CAP during the influenza season. The goal is to improve quality by preventing influenza and its complications.

Proportion of Patients with Smoking Cessation Offered

The proportion of patients with smoking cessation offered can be used as a quality indicator. For this indicator, the numerator is the total number of patients to whom smoking cessation was offered, and the denominator is the total number of smoker patients who were discharged from the hospital with CAP. The goal is to improve quality by preventing new episodes of CAP.

REFERENCES

l.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, File TM, Musher DM, Niederman MS, Torres A, Whitney CG. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44 Suppl 2:S27-72. [PubMed]

2.Mandell LA, Bartlett JG, Dowell SF, File TM Jr, Musher DM, Whitney C; Infectious Diseases Society of America. Update of practice guidelines for the management of community-acquired pneumonia in immunocompetent adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(11):1405-33. [PubMed]

3. Fletcher TJ, Tunnicliffe WS, Hammond K. et al: Simultaneous immunization with influenza vaccine and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine in patients with chronic respiratory disease. BMJ 1997;314:1663-1665. [PubMed]

4. Rhew DC: Quality indicators for the management of pneumonia in vulnerable elders. Ann Intern Med 2001;135:736-743. [PubMed]

5.Rennard SI, Daughton DM. Smoking cessation. Chest 2000;117:360S-364S. [PubMed]

Pathogenesis and Clinical Manifestations

Figure 1: The Alveolar Macrophage Acting as a Last-Defense Mechanism Against Bacteria that Reach the Alveolar Space

Figure 2: Recruitment of Phagocytic Cells to the Alveolar Space Mediated by the Local Production of Cytokines

Figure 3: The Clinical and Laboratory Manifestations of the Pneumonia Syndrome According to the Local or the Systemic Inflammatory Response.

Decision for Site of Care

Figure 4: Risk Factors Associated with a Complicated Course of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Figure 5: Step One of the Pneumonia Severity Index

Microbiologic Work Up

Table 1: Incidence of Common Etiologies of Community-Acquired Pneumonia

| 1. Typical pathogens | 40%-60% |

|---|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 15%-25% |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 2%-10% |

| Moraxella catharralis | 0%-5% |

| 2. Atypical pathogens | 10%-30% |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1%-10% |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | 5%-15% |

| Legionella pneumophila | 0%-15% |

| 3. Other pathogens | 5%-25% |

| Viral agents | 2%-15% |

| Pneumocystis carinii | 0%-10% |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 0%-10% |

| 4. Unknown etiology | 30%-60% |

Empiric Antimicrobial Therapy

Figure 6: Empiric Therapy for Patients Hospitalized in a Ward Without Risk Factors for Resistant Organisms

Figure7: Empiric Therapy for Patients Hospitalized in a Ward With Risk Factors for Resistant Organisms

Figure 8: Empiric Therapy for Patients Hospitalized in an Intensive Care Unit With No Risk Factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection

Figure 9: Empiric Therapy for Patients Hospitalized in an Intensive Care Unit With Risk Factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa Infection

Clinical Stability

Figure 10: Switch from Intravenous to Oral Therapy

The three periods during the recovery phase of hospitalized patients with community-

acquired pneumonia (Ramirez JA: Switch therapy in adult patients with pneumonia

Clin Pulm Med 1995;2:327-333.

Figure 11: The Switch From Intravenous (IV) to Oral Antibiotics is Performed at the Point of Clinical Stability

Figure 12: Switch Therapy Can Be Performed in a Patient with Community-Acquired Pneumonia With a Known or Unknown Etiology

Figure 13: Representation of Sequential Therapy and Step-Down Therapy According to Blood Level Achieved After Switch Therapy

ATB:Antibiotic

IV: Intravenous

Monitoring Clinical Outcome

Table 2: Patients at Higher Risk for Complications or Relapse.

| Microbes |

|---|

| Streptococcus pneumoniae Legionella pneumophila Staphylococcus aureus Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mycobacterium tuberculosis Pneumocystis carinii |

| Underlying Diseases |

| Immunosuppressive illnesses HIV Transplant recipient Chronic pulmonary disease Malignancy, especially lung cancer |

| Social Situation |

| Homelessness |

Figure 14: Group of Patients with Equal Final Outcome But Differences in Time to Clinical Improvement and Hospital Discharge (Early Outcome).

Figure 15: Correlation of Microbiologic Response with Clinical Response and Radiographic Response in Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia

Figure 16: Classification of the Clinical Course for Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia During the First 7 Days of Hospitalization

Figure 17: Correlation of Inflammatory Response and Clinical Picture

CAP: Community-Acquired Pneumonia

ARDS: Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome

What's New

Kim M, Blair J, et al. Coccidioidal Pneumonia, Phoenix, Arizona, USA, 2000–2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009 Mar;15:397-401.

Lodise TP, Kwa A, et al. Comparison of Beta-Lactam and Macrolide Combination Therapy Versus Fluoroquinolone Monotherapy in Hospitalized Veterans Affairs Patients with Community-Acquired Pneumonia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007 Nov;51:3977-82.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR

Reviews

Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis.2007.