Human papillomavirus in Transplant Recipients

Authors: Peter V. Chin-Hong, MD, MAS, John B. Lough, BA, EdM, Juan A. Robles, BA

Transplant recipients have a large burden of HPV-associated infection and disease. These include HPV-associated malignancies (cervical, anal, vulvar, vaginal, penile) and precancer lesions such as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) (1, 3, 7, 8, 9, 10-13). Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is one of the most common sexually transmitted infections worldwide affecting up to 80% of women by the age of 50, and likely a similarly large proportion of men as well. Although HPV is also associated with head and neck, as well as non melanoma skin cancers, the focus on this chapter will be in the cancers and non neoplastic lesions where there is ample evidence for the role of HPV.

Virology

Human papillomaviruses are small DNA viruses containing approximately 7900 base pairs. HPV infects epithelial tissues of skin and mucous membranes. There are over 100 distinct HPV subtypes. Among these, 15 have been designated at high-risk types based on their association with invasive cervical cancer (types 16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 59, 68, 73, and 82). HPV infection is an importance cause of more than 90% of cervical and anal cancers, and a large proportion of vulvar, vaginal and penile cancers. There is also strong association between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers. HPV type 16 accounts for about 50% of cervical cancer cases, with HPV type 18 contributing to an additional 20%. HPV can also cause disease with low malignant potential. The most common clinical manifestation of HPV infection is anogenital and cutaneous warts or condyloma. HPV types 6 and 11 infect the anogenital area and cause 90% of genital warts. These two types also cause recurrent respiratory papillomatosis. HPV type 1 commonly infects the soles of the feet and produces plantar warts. Transmission of anogenital HPV-associated diseases primarily occurs through any activity that involves genital skin contact and microtrauma, including genital-to-genital, and manual-to-genital contact. Cell mediated immunity is important for the control of HPV infection. Immunosuppression following solid organ transplantation decreases the ability to eradicate new HPV infection and permits increased HPV replication in latently infected cells. Consequently, HPV infection and HPV-associated disease are an important consideration in transplant recipients.

Epidemiology

Like in the HIV-infected population, there is an increased risk of malignancies among transplant recipients. This risk is of cancers with an infectious etiology such as HPV-associated cancers is substantial. In these patients, reduced immune surveillance may play an important role in increasing cancer risk. One systematic review by Grulich and others (n=31 977) reported increased standardized incidence ratios (SIR) of HPV-associated cancers in transplant patients compared to the general population (7). This included cancer of the cervix (SIR 2.1), vulva and vagina (SIR 22.8), penis (SIR 15.7), and anus (SIR 4.9). The following cancers possibly related to HPV were also found to have higher SIR compared to the general population: non-melanoma skin, oral cavity and pharynx, lip, esophagus, larynx and eye. Carcinomas of the anogential region have been reported to occur at an earlier average age (41 years) in transplant recipients compared to the general population.

It is likely that the increased risk of cancer is related to the higher prevalence of HPV-associated precancers and infection found in transplant recipients. One study from Scotland in the late 1980s reported that cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (49% in the transplant recipients versus 10% in the controls) and high-risk HPV types 16 and 18 (27% versus 6%) were present more frequently in renal transplant patients compared to age-matched controls. In a more recent report, 7% of transplant recipients in Italy were found to have abnormal cervical cytology following transplant; all patients had negative Pap tests prior to transplantation.

Like cervical cancer, HPV infection causes anal cancer (1, 3). Transplant patients have a higher risk of anal HPV, anal precancer lesions as well as anal cancer compared with the general population. In a systematic review of renal transplant recipients the prevalence of anal HPV infection was 47% in established transplant patients, and 23% in new transplant patients. The prevalence of anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) was 20% (10).

The association between HPV infection and a subset of oropharyngeal cancer is striking (6). D’Souza and colleagues conducted a case-control study demonstrating this association. Seropositivity for HPV type 16 (odds ratio 32.2) and presence of HPV oral infection (odds ratio 14.6) were independently associated with oropharyngeal cancer. In a study investigating HPV infection in the oral cavities of 88 Australian renal transplant recipients and 88 immunocompetent controls, HPV DNA was detected in 18% of transplant and 1% of control samples. However, an identifiable precancer lesion has not yet been identified as in the case of other HPV-associated malignancies, and efforts are underway to attempt to understand the natural history.

The relationship between HPV and non melanoma skin cancer in transplant recipients is also not clear. In one case-control study looking at 252 squamous cell carcinoma patients and 461 controls, HPV antibodies were more likely to be detected in the skin cancer patients compared with the controls (odds ratio 1.6) (8). The standardized incidence ratio of non melanoma skin cancer was 28.6 when comparing transplant patients to the general population in the Grulich systematic review.

HPV infection also causes non-malignant disease such as cutaneous and anogential warts with a large proportion of patients affected. The prevalence of cutaneous warts in transplant recipients is proportional to the duration of immunosuppression, increasing to 50-90% in patients more than 4-5 years following transplantation. Respiratory papillomatosis is another lesion caused by HPV with low malignant potential, found primarily in young children who aspirate HPV on to the vocal cords from mothers’ genital secretions during birth.

Clinical Manifestations

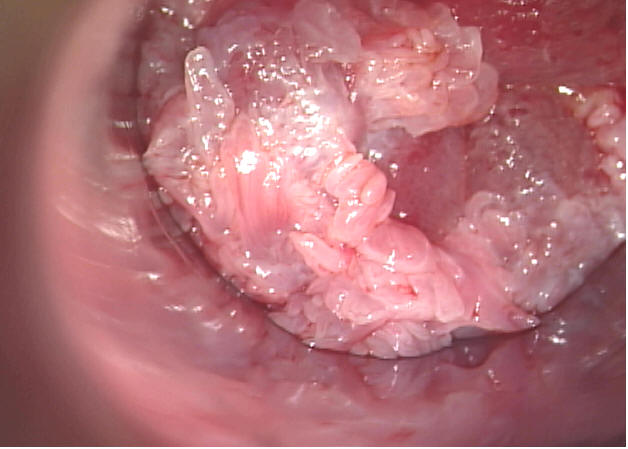

Cutaneous warts appear as characteristic well circumscribed exophytic papules that may be pedunculated, with normal adjacent skin. Some warts may be flat. Warts range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters, and some may coalesce to form plaques. Warts occur on any epithelial surface, frequently on the plantar and palmar areas. They occur commonly in the anogenital areas as well. The clinical presentation of anogenital warts in transplant recipients is consistent with presentation in the non-immunocompromised population, though with higher prevalence, recurrence, larger and more numerous in the immunocompromised patients. Like cutaneous warts, anogenital warts are typically multifocal and present clinically as exophytic with a characteristic ‘‘cauliflower’’ (condylomata acuminata) lesion (Figure 1) or appear flat. Condyloma acuminata are most commonly found on moist surfaces such as the vaginal introitus, preputial sac, or perianal area. Papular genital warts typically appear as smooth, circumscribed, elevated lesions and are found on dry surfaces such as the shaft of the penis in men, the outer parts of the female genitals, and the perineum. With the aid of 3-5% acetic acid, cervical warts often appear as flat condylomata during colposcopy examination. Patients with warts may complain of itching, burning, bleeding and pain. Those with large genital warts may have a sense of fullness. Infants with respiratory papillomatosis may present with stridor. However, many patients have no symptoms. Cervical and anal cancers, as well as high-grade HPV associated cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) do not often present with clinically identifiable or palpable markers such as anogenital warts. Hence screening is important for these lesions (see below).

Screening and Diagnosis

General Principles

The diagnosis of HPV related-disease in transplant recipients begins with a complete physical examination. A skin examination is important for non-melanoma skin cancer that may be HPV-associated, but also for skin lesions that are caused by HPV such as exophytic anogenital and cutaneous warts. Cervical Pap testing to detect and treat cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) is one of the most important interventions can be performed in transplant recipients. It is also the opinion of these authors that like in the case of HIV-infected individuals, anal cancer screening should also be offered to transplant recipients if there is an infrastructure to screen and treat anal intraepithelial lesions (AIN) (see below).

Special examinations and tests are available for the diagnosis of HPV infection, precancer lesions and cancer.

Colposcopy

Colposcopy with acetic acid is used to identify HPV-associated lesions. The technique uses a powerful light source and binocular lenses to aid in the identification of lesions, typically in conjunction with acetic acid. After the application of 3-5% acetic acid for 3-5 minutes, an acetowhite area (in contrast to the normal appearing surrounding tissue) indicates HPV infected tissue. This technique has now been adapted to other HPV vulnerable sites such as the anus (high resolution anoscopy [HRA]) and the penis. Following an abnormal cytologic test, colposcopy and HRA are used to identify, confirm (via biopsy) and treat precancer lesions.

Cytology

The Pap test is a cytologic test, and the cornerstone of cervical cancer and CIN screening (see below). Cervical cytologic findings are classified as normal or abnormal. The abnormal category includes atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASC-US] , ASC suspicious for HSIL [ASC-H], low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [LSIL] and high-grade SIL [HSIL]. Cytologic tests have also been adapted for anal cancer and AIN screening using a similar classification system.

Histology

Biopsies are used for definitive diagnosis of abnormal areas identified by colposcopy or HRA. The grading schema CIN I to III reflect the degree of histologic abnormality observed on biopsy. CIN II and III are considered high-grade lesions and the precursors to invasive cancer. The analogous lesions in the vulva (VIN), vagina (VaIN), anus (AIN) and penis (PIN) are graded in a similar fashion.

Molecular Methods

Techniques that use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and hybrid capture technology are sensitive and specific methods for diagnosing HPV infection. PCR uses the action of DNA polymerase on specific primers to amplify target HPV DNA. Type-specific HPV information can be obtained in this fashion. However, this is primarily used as a research tool. Hybrid capture uses RNA probes specific for the identification of certain grouped oncogenic (high-risk) or non-oncogenic HPV-types, but no HPV type specific information is obtained.

Serology

Enzyme-linked immunoabsorbent assay (ELISA) technology can be used to provide IgM and IgG serologic measures of HPV infection by targeting type-specific viruslike particles. However these methods are variable from laboratory to laboratory, are not standardized, and are currently used in research settings only.

Cervical Cancer and Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia Screening

Examination of the external genitalia is conducted using a magnifying glass and a bright light source. If genital warts are present, we recommend further evaluation since genital warts may co-exist with concomitant CIN. Because of the long preinvasive state of the precancer lesion associated with cervical cancer (CIN) and because CIN can generally be successfully treated when identified, cervical cancer screening has been very successful where it has been adopted. Guidelines for cervical cancer screening have been instituted by several expert groups including the American Cancer Society, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

In general, women should initiate Pap screening at age 21. If younger than 30 years old, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommend that women get screened every two years, and then annually for women 30 years and older. If women have had three consecutive negative Pap tests, and who have no history of CIN II or III, the screening interval in these women may also be extended to every 2-3 years in these cases.

However, we recommend that all transplant recipients be screened with the same periodicity as women who are HIV-infected. For these women, a cervical Pap test should be performed every six months for the first year. If these tests are normal, then annual screening is adequate. This approach is also recommended by the United States Preventative Services Task Force. Some providers use hybrid capture HPV testing (negative for a high-risk HPV type) for further reassurance that Pap screening intervals be increased from every six months to annual screening, and continue screening every six months if positive for a high-risk test. Others discuss performing screening colposcopy at the first visit for immuncompromised women. In general, we believe that the U.S. Preventative Services Task force recommendation of semi-annual Pap screening for the first year, followed by annual Pap testing is reasonable for transplant recipients.

Anal Cancer and Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia Screening

Because cervical and anal cancers have several similarities (they both arise in the transformation zone, they are both caused by HPV and are preceded by precancer lesions), Chin-Hong and Palefsky have proposed an anal cancer screening program that incorporates many of the elements of cervical cancer screening. We recommend anal cancer screening for transplant recipients where there is an infrastructure to do so. Other populations for which we recommend anal cancer screening are those who have a high risk of anal cancer; these include all HIV-infected women and men, men who have sex with men, and women with a history of vulvar or cervical cancer.

The anal Pap test is easy to obtain. To perform an anal Pap test, we recommend using a water-moistened polyester swab (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). Polyester swabs are used because cells cling to cotton and may decrease the yield of the Pap test. Insert the polyester swab into the anal canal, then withdraw the swab slowly while rotating the swab and maintaining pressure against the anal canal. Like what is done in cervical Pap tests, the goal is to obtain exfoliated cells from the areas at risk of HPV-associated disease. In this case, cells from the lower rectum, the squamocolumnar junction and the anal canal are obtained. Like cervical Pap tests, a glass slide or liquid-based media can be used to collect and transport these cells for analysis.

Based on the referral algorithm established for cervical cancer screening, individuals who are found to have abnormal anal cytology (atypical squamous cells of undetermined significance [ASC-US] , ASC suspicious for HSIL [ASC-H], low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions [LSIL] and high-grade SIL [HSIL]) are referred to the next step which in the case of anal cancer screening is high resolution anoscopy (HRA). HRA is similar to cervical colposcopy and uses identical equipment comprised of a powerful light source and binocular lenses. We use HRA to identify and biopsy lesions that have contributed to the cytologic screening abnormalities. Tools such as 3% acetic acid and Lugol’s (iodine) solution can increase the ability to identify abnormal lesions.

Pathogenesis

Most HPV is acquired sexually. After the acquisition of HPV infection, HPV is initially established in the basal cells of the epithelium. As the basal cells differentiate and rise to the epithelial surface, HPV replicates and virions form. A range of disease states can then ensue, depending on the degree of mitotic activity and replacement of the epithelium with immature basaloid cells. In the cervix this can range from genital warts or mild dysplasia (CIN I) to moderate or severe dysplasia (CIN II and CIN III). The analogous anal lesions are AIN I-III.

THERAPY

General Principles

There are several goals in the treatment strategy of HPV-associated cutaneous and external genital warts, as well as malignant and premalignant disease (3, 14). This depends on the size, location and grade of the lesion. Cutaneous and external genital warts have very little malignant potential. Goals of treating these lesions are for cosmesis or to relieve anxiety. In immunosuppressed patients, these warts may become quite large. In these cases removal of warts may be necessary due to the development of symptoms such as obstruction (in the case of anogenital warts), itching and bleeding. CIN I has a very low malignant potential but some providers may treat this lesion in HIV-positive women and transplant recipients. This is based on observations in clinical studies showing the rapid progression from low-grade to high-grade disease among patients with HIV disease. Like CIN I, AIN I has a very low probability of progression to cancer in general. However, AIN I may also be treated given the potential for rapid progression to high grade disease in immunocompromised patients. CIN II-III and AIN II-III are treated when possible as they are considered direct precursors to cervical and anal cancers respectively. Table 1 summarizes selected treatment options for HPV-associated diseases.

Treatment of External Genital Warts

Treatment options are categorized as patient or clinician applied. There is no evidence that one modality is superior to the other, and the method chosen should reflect patient and/or provider preferences, as well as take the experience of the provider into consideration. Although lesions may regress spontaneously in some, this is less likely in transplant recipients and HIV-infected patients. In addition, even if these lesions regress, many immunocompromised patients have recurrent disease 3-6 months following treatment. Warts that are smaller than 1 cm2 at the base are more likely to be treated with topical therapy only. Larger lesions may require surgical intervention. Sometimes we choose not to treat large, circumferential perianal warts if they are not symptomatic. This is because complete treatment usually requires multiple staged procedures which are painful, and which may need to be repeated since these lesions commonly recur.

Patient applied therapeutic options include imiquimod 5% cream and podofilox 0.5% solution or gel. Imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara) is a topical immune response modifier that induces cytokines locally without a direct antiviral effect. We instruct patients to apply the cream once daily before bedtime, three times a week for up to 16 weeks. Patients wash off the affected area with soap and water 6-10 hours following the application of the cream. Adverse effects include mild to moderate local erythema. Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (Condylox) arrests the cell cycle in metaphase leading to cell death. Patients apply the gel with a finger or the solution with a cotton swab, twice daily for 3 days on, 4 days off, with a maximum of 4 cycles. Adverse effects include local skin irritation. However, ulceration and pain can occur depending on the duration of use.

Provider applied therapies include cryotherapy, podophyllin resin 25% and trichloroacetic acid 80%. Cryotherapy can be performed using liquid nitrogen spray, a liquid nitrogen soaked swab, or a cryoprobe cooled with nitrous oxide. The freeze margin should extend 2-3 mm beyond the margin of the wart. Cryotherapy can be repeated every three weeks. Pain, swelling and erythema can occur. Podophyllin resin 25% in tincture of benzoin (Podocon-25, Paddock Laboratories, Minneapolis, MN) is applied to the affected area by the health care provider, left to dry, and washed off after 6 hours (maximum 0.5mL per session). This process can be repeated in one week. Like the related podofilox 0.5%, adverse effects may include local irritation, pain and/or swelling, depending on the duration of therapy. Infrequently, polyneuritis, paresthesias, leucopenia, and thrombocytopenia have been described. Tricholoroacetic acid (TCA) 80% can be applied to the affected tissue until it looks white or frosted. If TCA inadvertently gets on the surrounding, healthy tissue, this may be painful. To reduce this likelihood, we soak the stick end of a cotton swab in a small amount of TCA, and apply this to the lesion in a more precise fashion. Multiple cycles of treatment are often needed.

Surgical options for the treatment of condyloma include infrared coagulation, laser surgery, and scissor excision. The infrared coagulator (Redfield Corporation, Rochelle Park, NJ) is an FDA-approved device used to treat genital warts. This office-based procedure is particularly useful for larger lesions that would have otherwise required intraoperative fulguration. Laser surgery is another option for larger and more extensive condyloma. Adverse effects include pain and scarring. In contrast to infrared coagulation where no smoke plume is produced, laser operators may develop warts if adequate protection is not taken since virions can be dispersed during the procedure. Laser surgery is typically performed in the operating room under anesthesia and is generally more expensive compared with some of the other methods. Finally, scissor excision is performed by excising the wart down to normal tissue or mucosa using fine scissors or a scalpel. The roots of the lesion are then destroyed using cautery. Adverse effects include strictures and scarring, especially if subcutaneous tissue or fat is inadvertently cauterized.

Treatment of Cutaneous Warts

In all methods, paring down of dead skin using a pumice stone, nail file, emery board or scalpel is important to maximize the chance of cure. Soaking the affected skin for several minutes prior may help with paring. The best evidence for the successful treatment of cutaneous warts is the use of products containing salicylic acid. Other common options include cryotherapy and imiquimod 5% cream. Salicylic acid comes in numerous preparations, many of which are available without a prescription. The use of salicyclic acid in conjunction with an occlusive dressing such as duct tape may increase the efficacy of the intervention. Treatment should ideally be continued for 1-2 weeks following the physical removal of the wart so as to minimize the chance of recurrence. Cryotherapy and imiquimod 5% cream are used as described above. For atypically appearing, recalcitrant and recurrent cases, we recommend referral to a dermatologist for biopsy to rule out squamous cell carcinoma or other diagnoses given the high incidence of skin malignancies in transplant recipients.

Treatment of Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer treatment depends on whether disease is early or late staged. For disease up to stage IIa, patients can be treated either with surgery (radical hysterectomy with para-aortic and pelvic lymphectomy) or non-surgical methods (primary radiotherapy [RT] with chemotherapy). The advantage of surgery alone is the ability to retain functional ovaries. Conization is an option that may be offered to young women wishing to maintain fertility in early stage microinvasive disease (<3 mm). For bulky early stage disease, surgery followed by radiotherapy may be necessary. For locally advanced disease, RT followed by chemotherapy is usually chosen. For women with metastatic disease, chemotherapy can be used for palliation.

Treatment of Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Histology and immune status play a role in the decision to treat CIN. CIN I is generally of low malignant potential and generally not treated. However, because the natural history of CIN may be more unpredictable in transplant recipients and HIV-infected women, some clinicians may have a low potential to treat. CIN II and CIN III lesions are treated in all women to prevent cancer.

A variety of modalities may be used. Local excisional biopsy is one of the simplest methods used but this may be challenging if the lesion extends into the endocervical canal. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is generally the treatment of choice for CIN II and CIN III. In this procedure, an electric wire loop is used to diathermically excise lesions of various dimensions. LEEP is used extensively because in general it is easy to perform, has a low complication rate, and relatively well preserved tissue can be obtained for pathologic confirmation of clear disease margins. Cryotherapy employs the direct application of a supercooled probe to affected cervical tissue. Multiple freeze-thaw cycles are used. Adverse effects include mild cramping and persistent vaginal discharge. The advantages of this method include low cost, ease of use and low complication rate. However, disadvantages of cryotherapy include a higher failure rate compared with LEEP, and the inability to get tissue for assessment of treatment adequacy. Laser therapy is a method used during colposcopy that uses carbon dioxide to precisely vaporize lesions to an adequate depth. Advantages of laser include minimal bleeding and scarring since the surrounding tissue is only minimally affected in this method. The disadvantages include high cost, the specialized training needed, and like cryotherapy, the inability to get tissue to assess the adequacy of treatment. Cold-knife conization involves the use of a scalpel to excise a cone-shaped portion of the cervix including the entire transformation zone, usually if the patient is not suitable for treatment by LEEP or laser. Higher quality tissue is obtained for pathologic analysis. However, general anesthesia must be used, and there is a higher complication rate (eg, bleeding, infection, cervical stenosis, cervical incompetence, and scarring) compared to the other procedures which are office-based. In intractable cases, hysterectomy is performed.

Treatment of Anal Cancer

Invasive anal cancer is usually treated with combined-modality therapy (CMT) using both radiotherapy (RT) and chemotherapy (5-fluorouracil and mitomycin used together). The use of CMT can avoid the morbidity of abdominoperineal resection, where the anorectum is removed and a permanent colostomy is necessary. Immunosuppressed patients may experience CMT-associated toxicity. In this case, lower doses of RT and/or alternative chemotherapy such as cisplatin instead of mitomycin is sometimes used. If this is unsuccessful, then salvage therapy with abdominoperineal resection may be necessary.

Treatment of Anal Intraepithelial Neoplasia

It can be more challenging to treat AIN compared with CIN given the anatomical challenges posed by the anal canal. We treat AIN I for symptomatic or psychological relief, and if small enough, these lesions are easier to treat than the larger low-grade lesions. There is limited natural history data in transplant recipients, but in HIV-infected individuals, there is a faster progression from AIN I to AIN II/III compared to HIV-uninfected individuals. We treat AIN II and AIN III to prevent anal cancer. The size and location are also important factors to consider when deciding on the best strategy to treat. For intraanal (including anal condyloma) AIN I lesions < 1 cm2 at the base we recommend 80% trichloroacetic acid or cryotherapy. Some providers also use imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara) for internal lesions but there are less data to support this practice. If the lesions are larger or more extensive and not causing the patient symptoms, we may elect to follow these lesions and not remove them automatically. Often these large lesions require multiple procedures and can cause serious morbidity (pain, anal stenosis, anal incontinence). If the lesions are large and symptomatic, infrared coagulation or intraoperative fulguration (with guidance using high resolution anoscopy) can be used.

VACCINES

Therapeutic vaccines that target HPV-infected cells are potential future options for treatment. They work by augmenting the host cell-mediated immunologic response in an already HPV-infected individual. There are several methods. Many vaccines have used HPV E6 and E7 which are peptides of oncogenic HPV types used to activate host T cells. However, trials have been disappointing so far, and these vaccines are not ready to be used in clinical practice.

In contrast, trials of prophylactic HPV vaccines have been very effective in those unexposed to the types included in the vaccines. These vaccines use components of the major HPV capsid proteins (L1 alone or in combination with L2). The proteins self-assemble into virus-like particles (VLP) that contain no HPV DNA (so are not infectious). These VLP induce neutralizing antibodies before the host becomes exposed to HPV infection. There are two HPV prophylactic vaccines currently available (see Table 2 ). The first is a quadrivalent (HPV types 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (Gardasil, Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) and the other is a bivalent (HPV types 16 and 18) vaccine (Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium). HPV types 16 and 18 account for 70% of cervical cancers worldwide, and HPV types 6 and 11 account for 90% of all anogenital warts. Both vaccines have demonstrated over 90% efficacy in preventing CIN II or CIN III, adenocarcinoma in situ, and cervical cancer among women not exposed to the HPV types included in the vaccine. Both Gardasil and Cervarix have also demonstrated some cross protection against types not included in the vaccine with 20% and 50% efficacy respectively against CIN II or higher grade disease caused by HPV types 31, 33, 45, 52 and 58 (which account collectively for 20% of cervical cancers). In addition, because Gardasil also includes HPV types 6 and 11, it has demonstrated over 90% efficacy against anogenital warts caused by types 6, 11, 16 and 18 in both males and females not previously exposed. Gardasil also has demonstrated 78% efficacy against incident anal intraepithelial neoplasia among men who have sex with men.

Although there are not yet safety and efficacy data in transplant recipients, this is a non-infectious vaccine and not expected to be harmful. Nevertheless, these data are needed. The 2009 guidelines issued by the Infectious Diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation recommend HPV vaccination before or after transplantation in eligible patients (4). Note that vaccination does not substitute for ongoing Pap screening since not all oncogenic HPV types are included in the vaccine.

INFECTION CONTROL

The carbon dioxide laser is used in many medical procedures to vaporize, ablate, or cut tissue. There has been an increasing awareness of the potential health risks of a laser generated plume (aerosol). Several studies have demonstrated that intact HPV DNA virions can be recovered from the plume of carbon dioxide laser-treated human lesions (2, 5). In addition, there are reports of health care personnel who developed laryngeal papillomatosis containing HPV DNA types 6 and 11. Because of the potential for disease transmission, safety precautions during laser surgery are important. These include limiting the use of aerosol-producing lasers to patients for whom there is a strong therapeutic advantage over other modalities, protections of skin surfaces with gloves and gown, eye protection, and the use of masks and smoke suction systems that have high flow volume and good filtration.

REFERENCES

1. Albright JB, Bonatti H, Stauffer J, et al. Colorectal and anal neoplasms following liver transplantation. Colorectal Dis 2009. [PubMed]

2. Andre P, Orth G, Evenou P, Guillaume JC, Avril MF. Risk of papillomavirus infection in carbon dioxide laser treatment of genital lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;22:131-2. [PubMed]

3. Chin-Hong PV, Palefsky JM. Natural history and clinical management of anal human papillomavirus disease in men and women infected with human immunodeficiency virus. Clin Infect Dis 2002;35:1127-34. [PubMed]

4. Danzinger-Isakov L, Kumar D. Guidelines for vaccination of solid organ transplant candidates and recipients. Am J Transplant 2009;9 Suppl 4:S258-62. [PubMed]

5. Ferenczy A, Bergeron C, Richart RM. Carbon dioxide laser energy disperses human papillomavirus deoxyribonucleic acid onto treatment fields. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990;163:1271-4. [PubMed]

6. Gillison ML. Oropharyngeal cancer: a potential consequence of concomitant HPV and HIV infection. Curr Opin Oncol 2009;21:439-44. [PubMed]

7. Grulich AE, van Leeuwen MT, Falster MO, Vajdic CM. Incidence of cancers in people with HIV/AIDS compared with immunosuppressed transplant recipients: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2007;370:59-67. [PubMed]

8. Karagas MR, Nelson HH, Sehr P, et al. Human papillomavirus infection and incidence of squamous cell and basal cell carcinomas of the skin. J Natl Cancer Inst 2006;98:389-95. [PubMed]

9. Ogilvie JW, Jr., Park IU, Downs LS, Anderson KE, Hansberger J, Madoff RD. Anal dysplasia in kidney transplant recipients. J Am Coll Surg 2008;207:914-21. [PubMed]

10. Patel HS, Silver AR, Northover JM. Anal cancer in renal transplant patients. Int J Colorectal Dis 2007;22:1-5. [PubMed]

11. Paternoster DM, Cester M, Resente C, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia in transplanted patients. Transplant Proc 2008;40:1877-80. [PubMed]

12. Vajdic CM, McDonald SP, McCredie MR, et al. Cancer incidence before and after kidney transplantation. JAMA 2006;296:2823-31. [PubMed]

13. Villeneuve PJ, Schaubel DE, Fenton SS, Shepherd FA, Jiang Y, Mao Y. Cancer incidence among Canadian kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant 2007;7:941-8. [PubMed]

14. Workowski KA, Berman SM. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2006. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1-94. [PubMed] ![]()

Figure 1. Internal Anal Condyloma in a Kidney Transplant Recipient.

Courtesy Dr. Michael Berry, University of California at San Francisco.

Table 1. Selected Therapeutic Options for HPV-Associated Disease

| Drug/Therapy | Indication | Dose | Duration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-applied | |||

| Imiquimod 5% cream (Aldara) | Cutaneous, external and internal (selected) genital warts | Apply once daily before bedtime, three times a week

Wash the affected area with soap and water 6-10 hours following the application |

Up to 16 weeks

|

| Podofilox 0.5% solution or gel (Condylox) | External genital warts | Apply twice daily for up to 3 days, followed by no therapy for 4 days

Total daily volume not to exceed 0.5 mL |

Up to 4 weeks/cycles |

| Salicylic acid (various brand names and strengths) | Cutaneous warts | Apply patch or solution at bedtime after soaking and paring lesion with nail file or pumice stone

Use higher concentration (eg, 40% patches) if thicker skin (eg, soles) involvedMay use together with occlusive dressing (eg, duct tape) |

Assess after 2 weeks, may need treatment for weeks or months |

| Provider-applied | |||

| Cold knife conization | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | Performed with a scalpel to remove a cone shaped area of the cervix. Includes the removal of the entire transformation zone. | Follow up with cervical cytology and colposcopy 3 months after procedure. |

| Cryotherapy | Cutaneous warts, external genital warts, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade I (CIN I)

|

Applied as liquid nitrogen spray, or a soaked swab, or as a nitrous oxide cooled cryoprobe (CIN I)

Cutaneous: Aim for freeze to disappear within 60 seconds (plantar or palmar), including tissue 2-3 mm beyond the margins of the wart.CIN I: Perform a 3-minute freeze using the cryoprobe then allow the cervix to thaw. Repeat at least once. |

Can be repeated every 3 weeks |

| Infrared coagulation | Cutaneous, external and internal genital warts, anal intraepithelial neoplasia | Apply 1.5 second pulse of irradiation in the infrared range to affected tissue. Debride coagulated tissue using biopsy forceps. |

|

| Laser | External and internal genital warts, cervical and anal intraepithelial neoplasia | Using protective eye wear, a CO2 laser is directed at the affected tissue which is destroyed by vaporization (visible lesions). | For conization, follow up with cervical cytology and colposcopy 3 months after procedure. |

| Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) | Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia | A loop-shaped thin wire with a current is used to excise the transformation zone. | Follow up with cervical cytology and colposcopy 3 months after procedure. |

| Podophyllin resin 25% (Podocon-25) | External genital warts | Apply to affected area, then wash off after 6 hours. Not to exceed 0.5 mL per session.

May be used in combination with cryotherapy. |

May repeat therapy in 1 week. |

| Scissor (or knife) excision | External genital warts | Lesion is excised down to normal tissue with cauterization. | |

| Tricholoroacetic acid (TCA) 80% | Cutaneous, external and internal warts, anal intraepithelial neoplasia | Small amount applied to lesion until it appears white or frosted and allowed to dry. Ensure that surrounding, healthy tissue not exposed to acid. | Can repeat every week for up to 6 weeks. |

Table 2. Commercially Available Prophylactic Vaccines for HPV

| Vaccine | Indications | Schedule | Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quadrivalent (HPV 6/11/16/18, Gardasil, Merck, Whitehouse Station, New Jersey) | Should be routinely offered to all females 11-12 years old

Can vaccinate as young as 9 years old, and as old as 26 years old if not previously vaccinatedBoys and men 9-26 years old can also be vaccinated |

Three doses at time 0, month 2 and month 6

|

Minimal

Mild to moderate localized pain, erythema, swellingSystemic reactions, mainly fever, seen in 4% of recipients |

| Bivalent (HPV 6/11, Cervarix, GlaxoSmithKline, Rixensart, Belgium) | Should be routinely offered to all females 11-12 years old

Can vaccinate as young as 9 years old, and as old as 26 years old if not previously vaccinated |

Three doses at time 0, month 1 and month 6 | Minimal

Mild to moderate localized pain, erythema, swelling |

D'Souza G, et al. Case-Control Study of Human Papillomavirus and Oropharyngeal Cancer. NEJM 2007;356:1944.

The Future II Study Group.Quadrivalent Vaccine against Human Papillomavirus to Prevent High-Grade Cervical Lesions. NEJM 2007;356:1915.

Guided Medline Search for

Bonnez W. Human Papillomavirus

ACIP: Bivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (HPV2, Cervarix) for Use in Females. MMWR. May, 2010.

ACIP: Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine (HPV4, Gardasil) for Use in Males. MMWR, May, 2010.

GUIDED MEDLINE SEARCH FOR RECENT REVIEWS

Simon RQ. The 2008 Nobel Prize in Medicine: Dr. Harald zur Hausen for his work on: Human Papillomavirus and Cervical Cancer. 2009